History of the Opera House: Elliot Erratt and a city in sorrow, Part 1

America entered World War 1 in April of 1917. In September of 1918, a branch of the John Phillip Sousa “Jackie Band” from the Great Lakes Naval Academy near Chicago toured Northern Michigan on a D and M Railroad car. The goal was to promote patriotism and sell war bonds.

In Cheboygan, church services were canceled so everyone could hear the patriotic speeches and enjoy the Jackie band at the Armory. Sadly, the Jackie Band also brought the Spanish flu. Leaving two boys in the Cheboygan hospital, the band continued its tour, carrying Spanish flu from town to town and leaving a trail of death.

Finally, in Bay City, police shut down the train and sent them back to the Naval Academy where 200 men were already quarantined. Over 45,000 U.S. soldiers died of the Spanish flu stateside and in France, contributing to a quick end to the war. Ten times as many Americans died in the pandemic as they did in the war. Devastation overshadowed the joy of victory.

The Cheboygan Opera House was hit hard. No acts traveled. Shows canceled. The Opera House remained open to help the community, holding fundraisers for organizations like the Red Cross and the Ladies Aid Society. As war ended and the Spanish flu began to clear by March of 1919, long-time manager Elliot Erratt faced the challenge of re-opening the Opera House for entertainment. He had to rebuild an audience. Like most of the country, Cheboygan was a city in grief, devastated by loss.

In March, Erratt booked “Uncle Sam’s Big Yankee Minstrels.” The Cheboygan Democrat ran the headline, “Battle-scarred Heroes Coming Home.” ‘The Yankee Minstrels’ will appear at the City Opera House on the evening of March 31. This is the first real show to appear in a long time, and no doubt will get a good house as they come well recommended.”

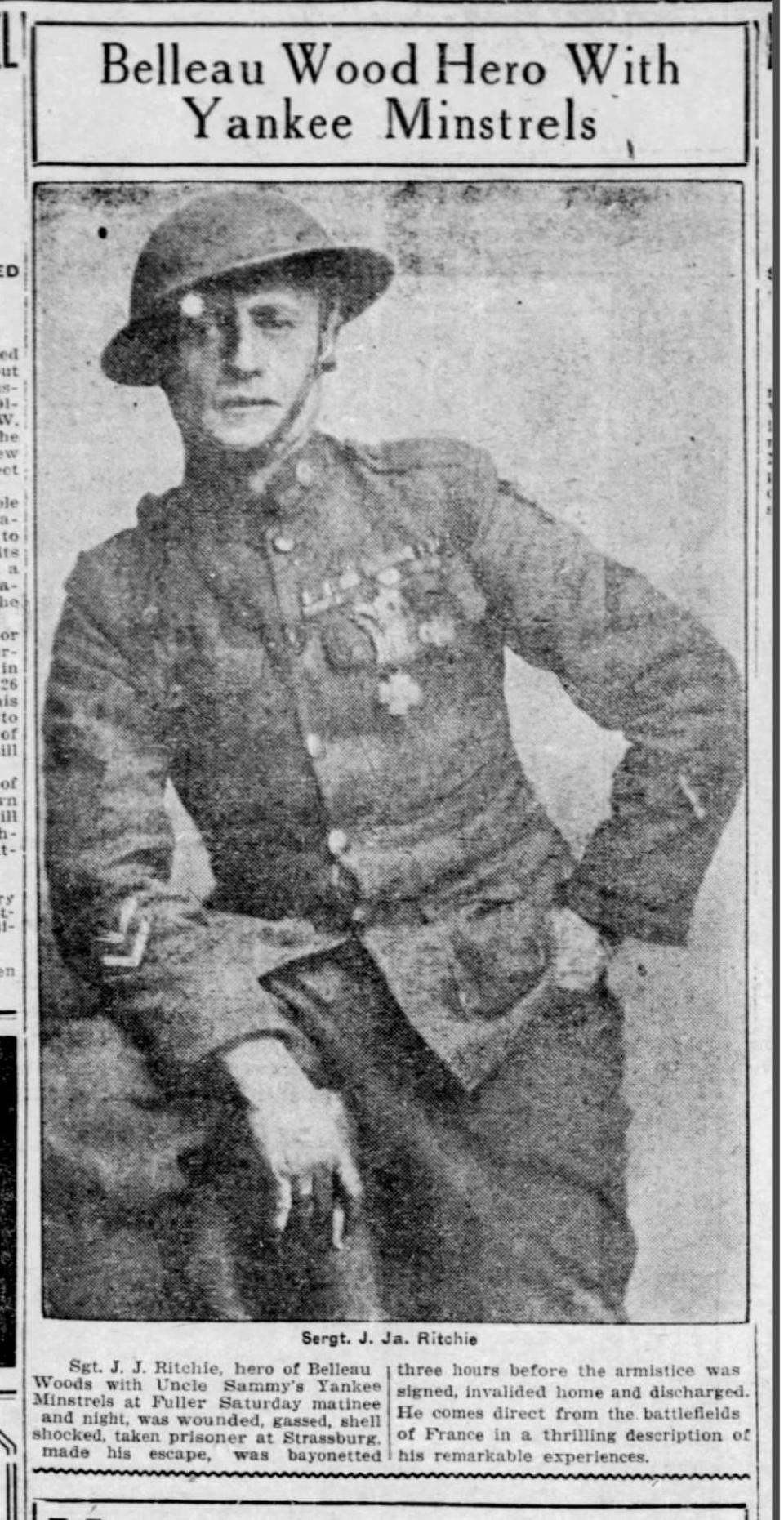

The show was a unique effort to put veterans who had been in the war back to work to help cheer the country. It was a variety show. The first half was a black-face minstrel act with songs, jokes and dancing. The second part featured war stories by Sargent J.J. Ritchie. The final act was satire called “Hunting the Huns.”

“Uncle Sam’s Minstrels which come to the City Opera House March 31, is composed entirely of wounded and returned soldiers, many of them so badly wounded they will never again be able to take up their regular vocation. Notwithstanding the fact that these boys have gone through Hell for us, they still have the ability to entertain, and after seeing their performance, one would never know they had suffered the hardships of war. Sargent Ritchie, the hero of Belleau Wood, will deliver his thrilling lecture, wonderful minstrel show is composed of some of the best entertainers and musicians that the army had. The Famous 87th Infantry Jazz Band and Orchestra will positively appear at each performance.”

Black American infantry bands brought jazz to Europe for the first time. A newly developing genre, jazz was a syncopated fusion of ragtime and blues. With its emphasis on improvisation, it is said to be music for the musicians, not the composers. Sending out Black military jazz bands to raise morale among the soldiers and among the civilians was a smash hit. After one show in France drew 50,000 people, Jim Europe, leader of the 369th Harlem Hellfighters band, said, “Everywhere we went was a riot.”

Some historians called jazz America’s greatest gift to Europe. Noble Sissel, lead vocalist for the 369th band added, “Who would have thought that the little U.S.A. would ever give to the world a rhythm and melodies that, in the midst of such universal sorrow, would cause all students of music to yearn to learn how to play it?"

When the jazz bands returned to America, some broke into smaller detachments. These touring detachments, like the one in the “Uncle Sammy’s Big Minstrel Show” spread jazz across the United States. The concertgoers in Cheboygan’s got their first taste of the sound that heralded the Age of Jazz. The Opera House curtain closed with the band playing George M. Cohan’s rousing anthem, “Over There.”

This article originally appeared on Cheboygan Daily Tribune: History of the Opera House: Part 67: Elliot Erratt and a City in Sorrow, Part 1