History of the Opera House: Tempers flare as infighting delays renovation

The resignation of City Manager William Arnold in December 1979 brought chaos. Arnold, who gave seven months’ notice per his contract, promised to find funds to finish the Opera House project before he left office. When he volunteered his time to write grants, he met opposition from city council member Louis Leblanc, "I don’t understand why he is still here. I disapprove of Arnold working on any city project,” LeBlanc told the Cheboygan Observer.

LeBlanc had concerns about the legitimacy of City Hall-Opera House project. When the city council took a vote to approve a bond to bring money to the Opera House, LeBlanc opposed it. “Chief opposition to the bonding issue plans came from Councilman Louis LeBlanc. LeBlanc said, “We have $2 million bucks in the City Hall building now and I would like to see a federal investigation into it.”

The council followed up with research into a federal investigation, reaching out to the Economic Development Agency who granted the city $1,681,000 to restore the City Hall-Opera House building. Interim City Manager Rush Cattell “told the council that he had contacted EDA by telephone and was advised that EDA could not conduct an investigation, as it is only a funding organization,” the Cheboygan Observer said. The federal investigation into City Hall was dropped on April 4, 1980.

Lawsuits also held up progress. When structural issues were first found within the City Hall building in 1978, the city council immediately fired the original architect, Douglas Morse Co. The city claimed Morse had failed to complete a structural analysis. They felt they could not afford to continue work on the Opera House because of the additional $400,000 necessary to fix the structural damages uncovered. The city council filed a lawsuit against Morse.

“The city paid Morse part of his contract fees before the trouble was found. The council voted authorization to city attorney Jeff Lyon to sue Morse to recover the money,” the Cheboygan Observer said. The city council wanted $40,000. Morse claimed his contract was breached when he was fired. He counter-sued for $45,000 in payment owed. In October of 1978, he offered to settle for $20,000. The city refused. The legal issue eventually went into arbitration that dragged on for two years. Both cases were dismissed in 1980.

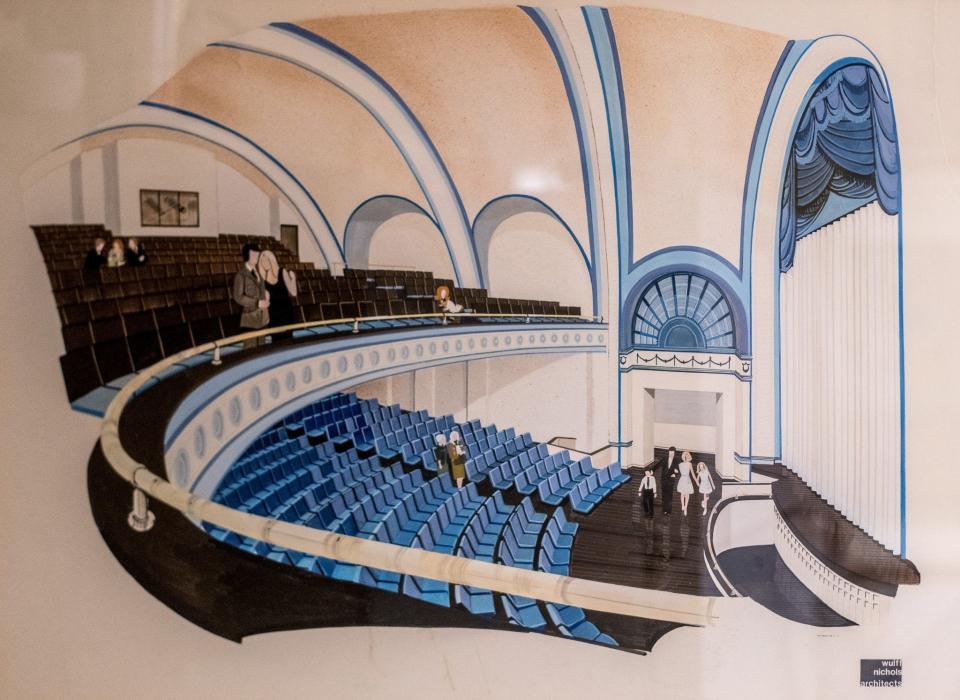

The architectural firm of Wulff and Nichols worked for the city to oversee the entire rebuilding. During the Morse arbitration proceedings, Wulff and Nichols testified multiple times in court on behalf of the City of Cheboygan. The city council did not pay their invoice for the work. Frustrated by the lack of progress on the building, the city council resorted to not paying contractors and threatening them with termination. In October 1979, “City council voted Tuesday night not to pay Tom Shaw for work done on the Opera House until the project is completely finished,” the Cheboygan Observer reported. “The stopping of payment was done to prod Shaw into finishing the project soon and also as a lever in case the work was not completed to the satisfaction of the council.”

During three years of in-fighting, investigations, lawsuits and workers not getting paid, work on the Opera House was stalled. On Jan. 16, 1981 the headline read “Opera House problems blamed on feuding. Peter Patrick, local attorney and spokesman for Tom Shaw on the City Hall-Opera House project said today that he feels the hold-up in the project is a result of a feud between contractor Shaw, and architects Wulff and Nichols.” But the problems went deeper.

On March 27, 1981, Wulff and Nichols resigned. The Cheboygan Observer said, “Tempers Flare. City Wrestles with Opera House. The architects had charged the city with failure to pay its bills, administrative interference on the project and refusal to grant the hourly rate hike. Nichols accused the council committee set up to oversee the project of numerous delays. He said, ‘City Manager Wright has been an asset to us, but the committee has not allowed us to make the judgments which we should be making according to our contract. Our authority is continuously being usurped by officials who do not know about the project. … If you can’t maintain our professional judgments then you don’t need us.’

Engineer and committee councilman James Muschell exploded at Nichols’ charge. ‘You use the term usurped inappropriately. We’re concerned with the quality of work, not your authority. The opera house committee spent many hours trying to protect the City so I don’t like your accusations,’ snapped Muschell.”

The Wulff Nichols company withdraw their resignation when the city agreed to pay off past due bills and to give the hourly rate hike. But nothing happened.

On Aug. 14, 1981, Gordon “Scoop” Turner wrote, “One of the things I mourn is the Opera House disaster. That beautiful auditorium on the second floor became unsafe because of fire safety rules and was closed. We vote the millage to restore it and remodel the City Hall. When the millage passed, people, rejoiced; they rang the City Hall bell and gathered and sang in the Opera House.

But the brick walls of City Hall were crumbling. It was so costly to save the building and to carry out the scheduled expansion and remodeling that the millage money was thrown into the pot. We have a fine City Hall now, though not nearly so beautiful as the original, and the Opera House space remains unfinished.”

More:History of the Opera House: Our beautiful Opera House — shall it be preserved?

To be continued ...

— Kathy King Johnson is former executive director of the Cheboygan Opera House.

This article originally appeared on Cheboygan Daily Tribune: History of the Opera House: Tempers flare as infighting delays renovation