History: Preserved Spanish architecture shows best of human potential

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Panama-California Exposition in 1915 was an unparalleled World’s Fair created ostensibly to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal and its first stop at San Diego on the way north up the western coast. Real estate developer Colonel D.C. Collier famously said the point was to “illustrate the progress and possibility of the human race, not for the exposition only, but for a permanent contribution to the world’s progress.”

Real estate developers, potentates, municipalities, and governments have sometimes been successful in demonstrating the best of human possibility. Sometimes not.

Franklin Roosevelt surveyed San Diego in 1915 when he was assistant secretary of the Navy. Seeing the exposition, he understood the area’s strategic importance and decided San Diego would become a Navy town.

After several prominent local families donated waterfront land, the United States Navy began building at Point Loma in 1921. It was a significant investment by the federal government and was, like the exposition itself, extremely ambitious.

New naval recruits began arriving in 1923, 100 years ago, at what would be the first permanent training center for the Navy on the West Coast. The project would expand exponentially in the next two decades, eventually consisting of 300 buildings on 550 acres. (During World War II over 33,000 people lived at the Naval Training Station. A significant proportion of the entire U.S. Navy was stationed in San Diego.)

The earliest permanent buildings were designed by Lincoln Rogers, who studied architecture in New York City at the Pratt Institute and Columbia University. He served as a commander in the Civil Engineering Corps of the U.S. Navy during the first World War.

The buildings and grounds were as spectacular as their waterfront setting and stately in their restraint. Influenced by Bertram Goodhue’s designs for the exposition, they were built in what would become known as Spanish Colonial Revival style.

Goodhue practically invented the style, blending the best of old Spanish Mediterranean vernacular with the optimism of Southern California. Having taken over from Irving Gill, whose style was more severe, Goodhue worked with Carleton Winslow Sr. and Lloyd Wright in creating what would become the dominant style in California for decades to come. (The style even leapt the ocean to the Territory of Hawaii for the 1920s building boom on the island, notably Goodhue’s Honolulu Museum of Art.)

Lloyd Wright, the eldest son of his very famous architect father Frank Lloyd Wright, trained in botany and horticulture and worked for the famous Olmsted firm. The exposition brought him to San Diego, but he would soon be working in Palm Springs, designing the Oasis Hotel for Pearl McCallum McManus and setting off a competition with Nellie Coffman who would retain William Charles Tanner to design Spanish Colonial Revival lodges and casitas for her Desert Inn.

(Interestingly in Los Angeles, Wright also worked with architect William J. Dodd, who designed the Mead and Bishop Houses, now The Willows, in 1924, immediately behind The Desert Inn in Palm Springs.)

Synthesizing the gorgeous proportions in San Diego’s Balboa Park Exposition buildings with the elegant restraint of the Naval Training Station compound, Tanner’s spectacular conception for The Desert Inn accommodations would invent his own local desert Spanish vocabulary. Tanner designed some of the most important buildings in Palm Springs including the Thomas O’Donnell House, Ojo del Desierto, and the George Heigho House, Invernada.

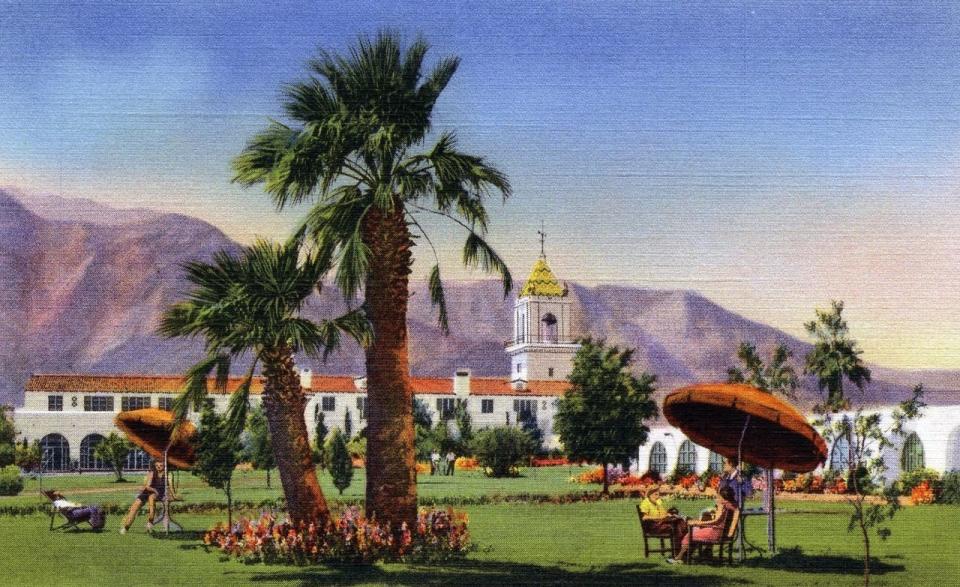

Only a few years later, Prescott Thresher Stevens was subdividing the Las Palmas neighborhood in Palm Springs and engaged prominent Los Angeles architects Walker and Eisen to build the El Mirador Hotel with an impressive view tower. The hotel featured expansive grounds punctuated with buildings in the romantic early California aesthetic by then already in evidence everywhere in the southern part of the state, and also right down the road at The Desert Inn.

Further down valley, Walter H. Morgan hired Gordon Kaufmann to design a magnificent hotel on 1,400 acres of land tucked into a cove of the Santa Rosa mountains. The main building would have been at home at points west, and the hotel was exceedingly gracious for visitors being housed in the original 20 guest casitas.

Considering the relative obscurity of the desert in the 1920s, it is remarkable that the Oasis Hotel, The Desert Inn, the El Mirador Hotel and the La Quinta Hotel came to fruition at all.

The most important builders and famous architects of the time were here in the desert as well as the big coastal cities. Their projects have been variously esteemed and come to different fates based on the imagination and creativity of the developers, potentates, municipalities, and governments involved.

Wright’s Oasis Hotel has long since been mostly demolished, its bell tower left in disrepair hidden behind the Oasis Commercial building at Tahquitz and Palm Canyon Way.

The La Quinta Hotel is now the La Quinta Resort and in the decades after its initial construction exploded with hundreds more hotel rooms and countless pools, but Kaufmann’s original core remains.

The crash of 1929 and the Depression caused Stevens to sell El Mirador. By World War II, the Army adapted it into Torney General Hospital. In November 1945 Torney General Hospital was closed and the Federal Works Administration sold the site, now occupied by Desert Regional Medical Center. Nothing much remains of the hotel except an administration building and a reconstruction of its grand tower.

The Desert Inn fared worst of all, having been tragically razed to the ground in the late 1960s in favor of an uninspired, multiply failed, ill-advised shopping mall, a concept puny and prosaic in comparison to the possibilities had it been preserved.

But, in San Diego, the decommissioning of the naval base in the early 1990s was seen as an unrivaled opportunity by the imaginative city. To avoid blight, potential degradation and disrepair, the City of San Diego began subleasing areas of the training center to small businesses, non-profits, city departments and found a master developer who was community-minded in Corky McMillin, a conscientious local citizen.

The rebirth of the Navy Training Center as Liberty Station is nothing short of miraculous and should be a model for cities everywhere. Now a vibrant Arts and Residential District, stepping onto the campus of Liberty Station is inspiring as a confection of life in a more gracious time and in a singularly beautiful, built environment.

On the National Register of Historic Places, along with its neighboring Balboa Park the site of the Exposition, Liberty Station demonstrates the best of preservation and is a precious asset for San Diego. In the desert, imagining what might have been makes Palm Springs’ losses even more painful.

A pleasant day trip from the desert to Liberty Station is most worthwhile and achieves a step back in time of a whole century; to a time when the world held the promise and possibility of human endeavor.

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Thanks for the Memories column appears Sundays in The Desert Sun. Write to her at pshstracy@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Palm Springs history: Spanish Colonial Revival style