History shows Binghamton's plan to go under doesn't go over well

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry. Somehow the poem with its Scottish flair by Robert Burns has a little more flavor, but through many generations that quote has come to mean that even with the best intentions, things can go wrong. In this instance, it was with the best intentions to keep people, especially children, safer, and to make travel easier for pedestrians without fear from a possibly horrible fate. Yet, that is not how it turned out.

Let’s take a trip back to the early 1930s, when railroads were an everyday and common experience in the Triple Cities. Both passenger and freight trains transverse the community, traveling at good speed pulling thousands of pounds of weight as they made their way from station to station. Add to this part of the equation, the increasing number of vehicles and people who needed to cross the railroad tracks to get to a store, school, or home.

While those numbers were increasing, so were the numbers of accidents between moving trains and people. Local officials were not alone in this concern, and New York State government established the Public Safety Commission to handle requests from locations that safety measures were required at one physical location or another.

Starting around 1930, plans were put in motion to create not only underpasses for vehicles, but pedestrian underpasses. The vehicle underpasses would eliminate at-grade crossings that were the locations of most accidents between trains and cars. Some of these new underpasses also included sidewalks for people to use, but many did not. In those locations, the creation of pedestrian underpasses seemed to be the best solution.

Business: Take it for an off-road test drive. New Matthews dealership features obstacle course

Local heroes: American Red Cross 'Real Heroes' awards: Here are the recipients and their heroic stories

Things to do: Get ready to sing and dance: These Broadway shows are coming to Binghamton in 2024

The concept was easy. The execution was not. The local officials, residents and the Public Safety Commission would find those locations where people needed to cross and create an underpass to take those people under the tracks, rather than over them. In 1932, the Commission approved three such underpasses located along the Erie railroad tracks. They were located at Oak Street, Murray Street and Crandall Street – all leading over to Clinton Street.

A similar underpass was approved between Elizabeth Street and Allen Street in Johnson City, and in Vestal, an underpass along the Lackawanna railroad lines was approved by North Main Street. All of these underpasses were planned to eliminate people from crossing over the tracks. While designs were similar, each had to conform to the space and land. Some were merely a passthrough, while others contained stairs and lengthy walkways to the entrances. The one in Vestal was built in a “u” formation.

In Endicott, petitions were made to build another underpass at North Loder Avenue, but attempts in the 1930s, 1940s, and early 1950s all failed as sidewalks were available at the Nanticoke Avenue underpass. Everyone agreed these appeared to be a good idea, and the cost of each one would be approximately $80,000. While it seemed to be good, problems began shortly after completion.

By the 1940s and into the 1950s, graffiti was painted on the walls. Users were often accosted by drunks, and at least one rape occurred in one Binghamton underpass. In Vestal, the tracks were abandoned and the underpass was closed in 1960s. In Binghamton and Johnson City, the underpasses were closed with gates to prevent access and to prevent even more crimes from occurring. What was a good idea had become a serious problem only a few years in existence, yet the closures took up to four decades to occur.

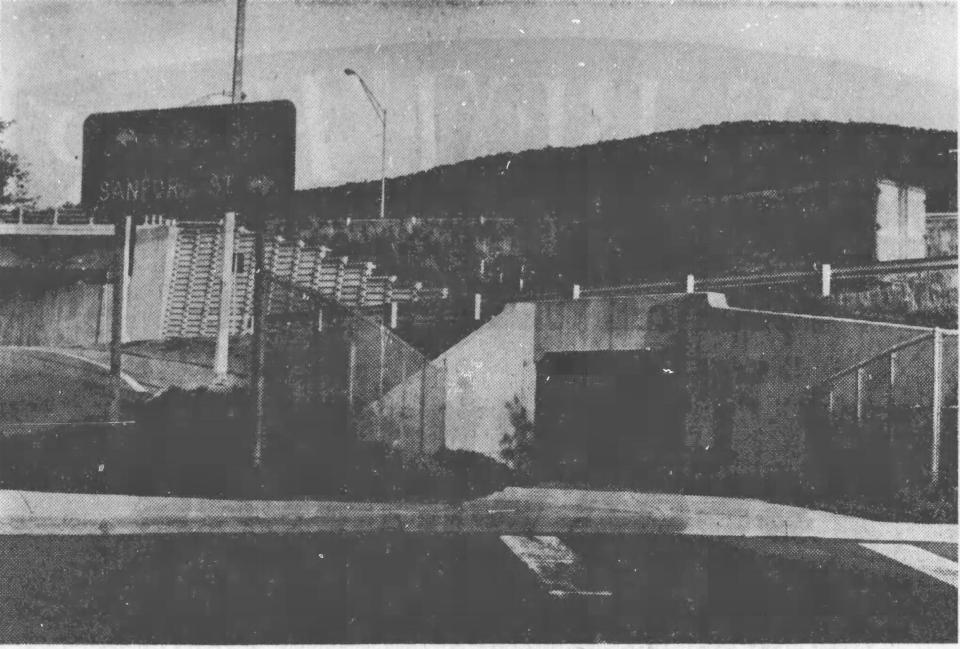

While all this was happening, we were not done with pedestrian underpasses, as two more were constructed in the 1960s. The first was located at the end of Carroll Street and under the then newly constructed North Shore Drive. While better in design, fencing had to be placed to prevent drivers of small cars from using the underpass to avoid the police. In Endwell, a large tube-like underpass was built at the end of Davis Street and under Route 17 to take walkers toward the Susquehanna River. It remains to be seen if these are any more successful than those built in the 1930s. Only time will tell.

This article originally appeared on Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin: Binghamton history includes short-lived plan to build underpasses