A history of slavery at Harvard University and beyond

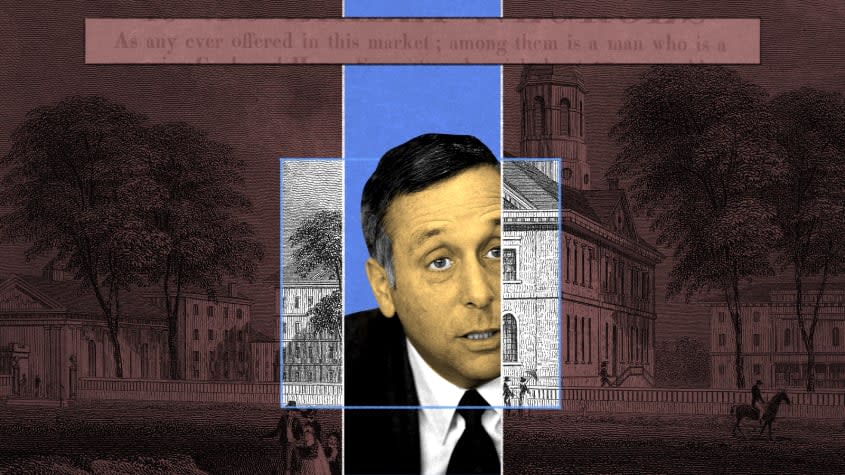

Harvard University President Lawrence Bacow said Tuesday that the prestigious school will set aside $100 million to study and redress its historic ties to slavery following the release of a committee report on the topic. Here's everything you need to know:

What are Harvard's ties to slavery?

In 2019, Bacow established the Presidential Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery to investigate "the University's historic ties to slavery — direct, financial, and intellectual."

The report states that from the founding of Harvard in 1636 until slavery was outlawed in Massachusetts in 1783, Harvard's faculty and staff enslaved 70 people. According to NPR, "[s]ome of those who were enslaved lived on campus and were responsible for providing care for Harvard's presidents, professors and students."

Harvard also profited from "the beneficence of donors who accumulated their wealth through slave trading; from the labor of enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean islands and in the American South; and from the Northern textile manufacturing industry, supplied with cotton grown by enslaved people held in bondage," the report reads. Isaac Royall Jr. (1719–1781), a wealthy merchant who owned and traded in slaves, left Harvard a bequest in his will that helped the school establish its first professorship in law. Harvard Law School even incorporated elements of Royall's coat of arms into its seal.

The report also notes that Harvard's leadership took steps to curb abolitionist sentiment on campus in the years before the Civil War and that the university's medical school admitted three Black students in 1850 but expelled them after some white students and alumni complained.

Racism continued to have an influence after the Civil War. Professors and administrators promoted the study of eugenics, and Harvard admitted only about three black students per year during the period between 1890 and 1940.

What steps is Harvard taking?

The report states that the committee's findings "not only reveal a chasm between the Harvard of the past and of the present but also point toward the work we must still undertake to live up to our highest ideals."

To fund that work, Harvard has created a $100 million Legacy of Slavery Fund. The report recommends that the fund be "preserved in an endowment, and strategically invested." Bacow confirmed Tuesday that some of the funds "will be available for current use, while the balance will be held in an endowment to support this work over time." He did provide a more specific breakdown.

According to CNN, the report's recommendations include "the expansion of educational opportunities for the descendants of enslaved people in the Southern U.S. and the Caribbean, establishing partnerships with historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), and identifying and building relationships with the direct descendants of enslaved people who labored at Harvard."

This fund is not Harvard's first attempt to atone for its historic ties to slavery, nor was Tuesday's report the first attempt to investigate them. A 2008 report shed light on Royall's ties to slavery, leading to the retirement of the law school's heraldic shield in 2016.

Also in 2016, then-President Drew Gilpin Faust publicly acknowledged that Harvard had been "complicit in America's system of racial bondage" and oversaw the installation of a plaque acknowledging the labor of four enslaved people who had served two of Harvard's presidents.

In 2020, Harvard Medical School's Oliver Wendell Holmes academic society was renamed due to Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.'s role in expelling the school's first Black students.

Do other American universities have historic ties to slavery?

Yes. Dozens of American universities have deep ties to slavery. The University of Virginia oversees a consortium known as Universities Studying Slavery (USS), which focuses on "sharing best practices and guiding principles about truth-telling projects addressing human bondage and racism in institutional histories." USS has 94 member schools.

UVA itself was founded by slave-owner Thomas Jefferson and benefitted from the labor of some 4,000 enslaved persons between 1817 and 1865. Dartmouth's founder, Eleazar Wheelock, owned slaves. So did Henry Rutgers, the namesake of the university in New Jersey. Yale is named after slave-trader Elihu Yale. Sixteen of the 23 founding trustees of Princeton were slave owners, as were its first nine presidents.

In 1838, Georgetown University sold 272 enslaved men, women, and children to plantations in the deep South to pay the cash-strapped Catholic college's debts. The enslaved people had previously worked on Jesuit-owned plantations in Maryland, where they were required to attend mass. Some priests expressed concerns that the slaves' new masters might prevent them from practicing their Catholic faith, but the sale still went ahead at the instigation of then-president Rev. Thomas F. Mulledy. In 2015, the university removed Mulledy's name from a campus building.

In 2019, Georgetown's student body voted overwhelmingly to increase tuition by $27.20 per semester to create a fund benefitting the descendants of those 272 slaves. The descendants are also considered legacy applicants by Georgetown's admissions office.

Other universities with historic ties to slavery have taken a variety of steps, including erecting plaques commemorating enslaved persons, re-naming colleges and campus buildings, and conducting further research.

In some cases, debates over the legacy of slavery have become contentious. School benefactor Johns Hopkins, the physician long touted as an abolitionist, was revealed in a 2020 report to have been a slave owner. The report found no evidence that Hopkins "held or acted upon antislavery or abolitionist beliefs." New York Times editor Steve Bell defended Hopkins, whom he argued was well respected by Baltimore's Black community and served alongside prominent abolitionists on the board of a school for Black girls. Bell also pointed out that Quakers like Hopkins frequently purchased slaves with the intent of freeing them, but were often required to maintain legal ownership — sometimes for years — due to laws regulating manumission.