On World AIDS Day, here's how 2 Ohioans are trying to help end the epidemic

Marko Phillips and Jet Jama have never met each other.

They grew up decades apart. And they're from completely different parts of the world.

But the two share a lot in common, including a medical diagnosis.

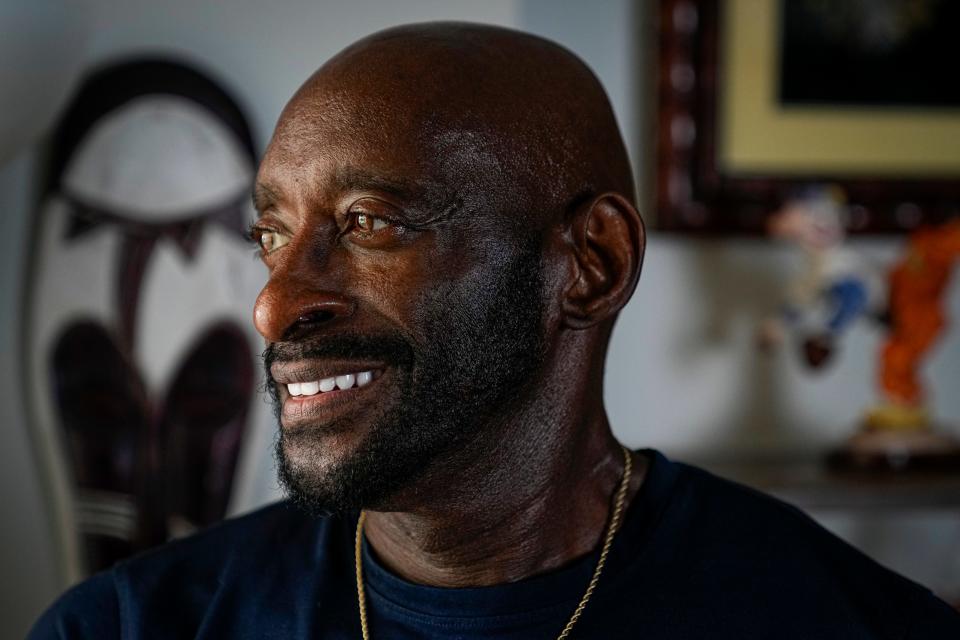

Both are members of the LGBTQ community; both are Black Ohioans now living in Greater Columbus; and both have HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Phillips, who identifies as a gay man, was diagnosed in 1994 while Jama, who identifies as gay and nonbinary and uses "they/them" pronouns, was diagnosed in 2022.

"It's a journey," said Phillips when asked what he would tell Jama about living with the disease.

"When I do talk to people, I give them the truth about how it is. I don't sugarcoat anything. It's rough," he said. "But the best power you can have is support, whether it is through a group of people or a friend or a family member. Finding support is most important."

Read More: Should you get the new COVID booster? Here's what OhioHealth's Dr. Joe Gastaldo says

As Black Americans, both Phillips and Jama are part of a group of people that carries the greatest burden of HIV.

Black Americans make up 12% of the U.S. population, but accounted for 40% — 13,000 cases — of the 32,100 new HIV diagnoses nationwide in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That disparity persists more than 40 years after the first case of AIDS showed up in the U.S. and since the first Ohioan died of the disease in 1981, according to the CDC and the Ohio Department of Health. The U.S. has set a goal of ending the HIV and AIDS epidemic nationwide by 2030.

With that deadline looming, bringing an end to new cases in the Black community faces an uphill battle fueled by a lack of access to care, homophobia, and racism, said Dr. Carlos Malvestutto, an infectious disease specialist at Ohio State University's Wexner Medical Center.

But the two most pressing causes for the disparity, he said, are the stigma associated with it and a lack of trust in health care providers.

"Part of that is: 'I don't want to get tested. I don't want to have to deal with this. I'm just not even going to pay attention to that because that's the way I protect myself. I don't trust that the system is there to take care of me,'" Malvestutto said.

Both Jama and Phillips wanted to share their stories in an attempt to shatter the stigma among Black Ohioans. It's why each decided to talk with The Dispatch about getting diagnosed, despite the painful memories associated with that time in their lives.

"It's just a stigma. I am healthy. I'm trying to be happy," Jama said. "That's why I decided to share my story at the end of the day, because it is not a death sentence anymore. It really isn't."

A chance diagnosis

Jama sat in their doctor's office overcome with anxiety.

It was early October 2022, and Jama had been feeling sick for a few weeks and was seeing a doctor for a routine checkup.

The doctor had ordered some lab work for Jama, who was worried they'd be diagnosed with something far worse than a run-of-the-mill illness.

As Jama waited for what felt like an eternity for the doctor to enter the exam room, they became convinced they already knew what the diagnosis would be. When the doctor came in, Jama said they panicked and word-vomited before the doctor could even speak.

"He came in and I told him right away: don't sugarcoat it," Jama said. "He didn't get like two words out before I started crying really, really hard."

Jama broke down.

In that moment, Jama had a million thoughts running through their head.

Read More: What does it mean to be a Native American tribe? In Ohio, the answer is complicated

Getting diagnosed with what could be a lifelong illness was just one more thing in a long line of challenges that Jama said they've faced.

On top of the diagnosis, Jama had just come out days earlier. What should have been an exciting milestone now felt like one of the toughest weeks Jama had in a long time.

Being nonbinary and gay is not something that is widely accepted in Jama's Somali Muslim community. When Jama came out earlier that week, they received death threats online from their own people.

Now, sitting in the doctor's office, Jama worried what the Somali community would think when it found out about their HIV diagnosis. Jama felt like the virus was "a curse" someone had placed on them.

"I was just hearing the words of people on social media telling me I should be struck down," Jama said. "I thought, maybe this is me being struck down. There was just a lot going through my head."

But as the days passed after that doctor's appointment, Jama said reality set in.

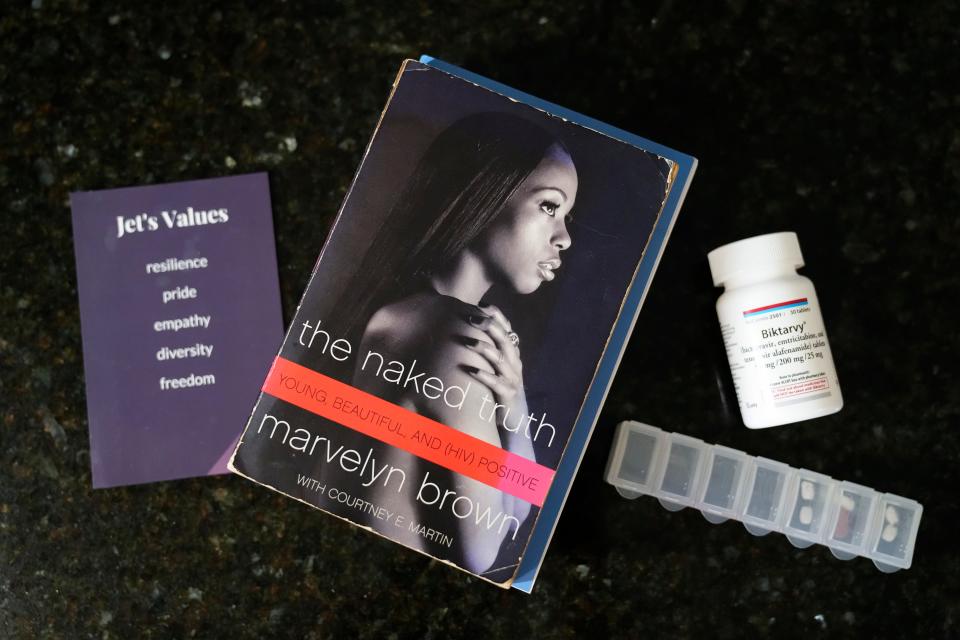

The diagnosis was still difficult to accept, but they went to work learning as much as they could. Jama started reading books about HIV and AIDS and met with doctors.

Jama got on a medication called Biktarvy, a drug commonly prescribed to make HIV undetectable in people with the virus.

And Jama began looking at enrolling in clinical trials for treatments rather than waiting for something new to become available years or even decades down the road.

Jama, who was afraid of getting tested for HIV, is now encouraging others to get tested and treated.

It's a complete turnabout from that day in the doctor's office when Jama felt afraid of what their doctor would diagnose them with and what it would mean.

"What scares me more than HIV is that if I didn't have that doctor's appointment, I wouldn't have known," Jama said. "I might never have known."

'My world just stopped and turned into a nightmare'

Phillips felt like his life was over.

It was 1999 and he was holed up in a hospital bed in the Cleveland area.

Phillips had been diagnosed with HIV five years earlier. But instead of getting the treatment he needed, Phillips ignored his illness and often didn't take his medication.

"I became sick. I became depressed ... I started to withdraw from life. I became bitter and angry and upset and as time went on, I started changing physically," Phillips said of the virus' toll on his body and his mental health. "It was like my world just stopped and turned into a nightmare."

Unable to really walk on his own, Phillip was largely confined to that Cleveland hospital bed.

Confined there one day, he had an epiphany. He finally realized he needed to make a change or else he wouldn't be around much longer.

Once he was released from the hospital, Phillips said he focused his attention on getting healthy.

He forced himself to take more than a dozen pills daily and eventually, his health returned.

He began seeing a psychiatrist and looking for support — a difficult task for Phillips, who felt like society had cast aside many people diagnosed with HIV and AIDS.

"I was just sad, and my thing was I stayed away from people," Philips said. "I did that because I was ashamed of who I was and (thought) nobody wants to be around somebody who has a disease."

But Phillips made a close friend in a support group. Having someone to lean on and hearing the stories of others who were going through the same thing caused Phillips to start "waking up."

Instead of feeling depressed, Phillips began telling himself: "I'm going to fight this. I'm going to survive this."

After years of living with the virus, Phillips began to see that he needed to do something to help others overcome its stigma.

It started with a speaking engagement at Cleveland State University, and has since led to speaking and advocating for people with HIV and AIDS around Ohio.

Today, Phillips said he's still speaking out when he can to make sure Ohioans know people like him are still here.

"I've learned so much and I have dedicated so much of my life to this," Phillips said. "People don't recognize we're still here. People don't know there are long-term survivors."

How to get tested for HIV

Testing is available at various locations throughout the greater Columbus area at little to no cost to patients. To find a testing site or book an appointment, visit the links below.

CDC Testing locator: gettested.cdc.gov

Columbus Public Health: columbus.gov/publichealth/programs/hiv-testing-and-care/

Equitas Health: equitashealth.com/our-services/hiv-advocacy/hiv-sti-testing-sexual-health-clinics/

mfilby@dispatch.com

@MaxFilby

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: On World AIDS Day, Black Americans carry heaviest burden of epidemic