Hochul wants to require schools to teach phonics. Does 'science of reading' support it?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

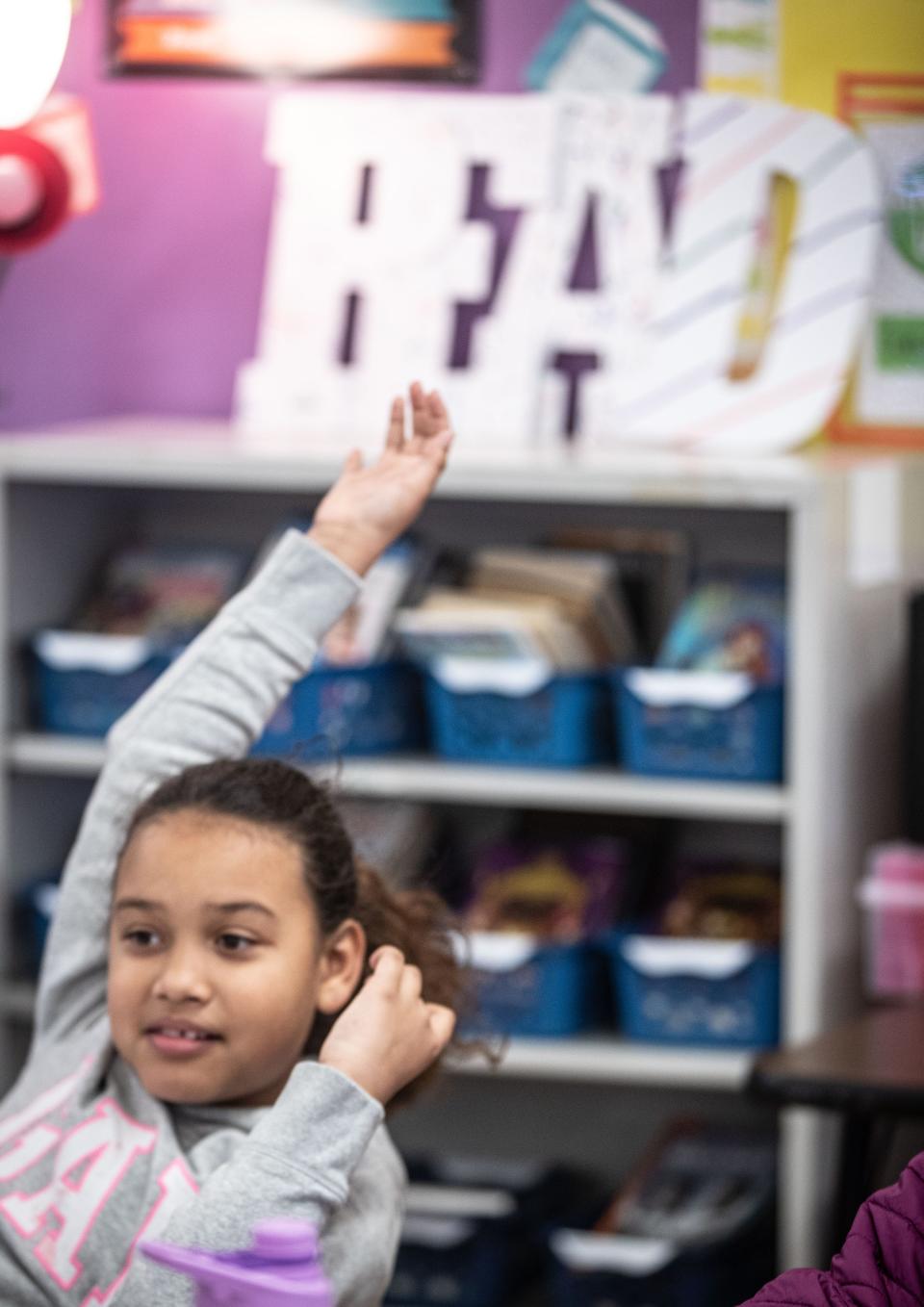

New York's youngest students may soon see a renewed focus on phonics, as the pendulum in the age-old debate over how to teach reading swings toward the so-called "science of reading."

Gov. Kathy Hochul has gotten behind a "back to basics" push, saying she'll propose legislation that would require New York's schools to use evidence-based, phonics-focused approaches for reading instruction. Among her proposals for the new year, she pledged $10 million in state money to train 20,000 teachers on these approaches.

"It's not just science. It's common sense," Hochul said last week of the science of reading.

Across the country, a mix of educators, parents and activists have insisted in recent years that research shows phonics — the systematic decoding of letters and sounds — is essential to effectively teach reading to most children, including those with reading disabilities.

This movement holds that other methods for teaching reading, which emphasize comprehension and developing a "love of reading," are responsible for students' poor reading scores across the country. Even if students get some phonics in those methods, many say it's not enough.

Hochul said New York students are also doing poorly, as only 48% of students in grades 3-8 were considered proficient after taking standardized English language arts tests this past spring.

In New York, school districts have the latitude to choose their own approaches to reading instruction.

When asked if the state Education Department supports Hochul introducing legislation requiring schools to use evidence-based approaches, a spokesperson said the department would wait until more details were shared to comment.

But the Education Department has gotten behind the science of reading push in other ways, joining a study to "transform early literacy instruction" and promising to share research at the local level on the science of reading.

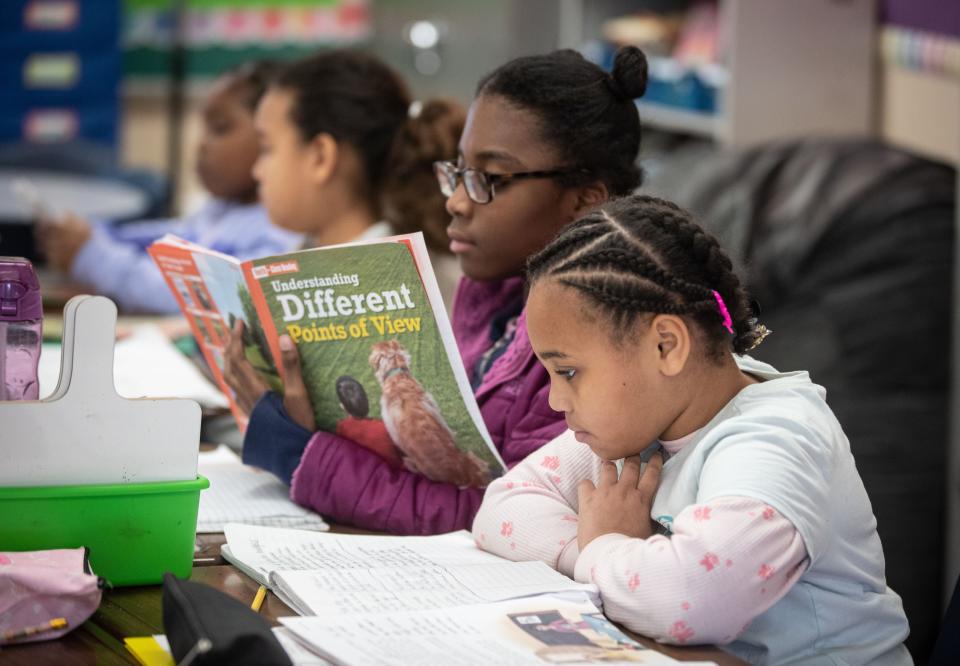

While Hochul emphasized phonics, educators in the Lower Hudson Valley say phonics is only one piece, albeit an important one, of the reading puzzle.

How we got here

Calls for an evidence-based return to the basics are, to some extent, a backlash against the "whole language" approach to reading instruction that became prominent during the 1980s and 1990s.

That approach focused on immersing students in reading of all kinds, positing that the decoding of letters, sounds and words comes naturally to kids.

Whole language is more of a top-down approach, starting with exposing children to rich language and stories, as opposed to the bottom-up approach of phonics, first learning letters and sounds, said Tracy McCarthy, managing director of the Rose Institute for Learning and Literacy at Manhattanville College.

"Envision them sort of on opposite ends of the paradigm," McCarthy said.

Then, in the 1990s, came the balanced literacy approach to reading instruction, which — as it sounds — kept elements of whole language but added back phonics.

"Balanced literacy comes after whole language, saying yeah, we need it all. We need decoding. We need phonics and we need great literature," said Mary Coakley-Fields, an associate professor in Manhattanville College's department of literacy and English education, and program coordinator for the Rose Institute for Learning and Literacy.

A balanced approach to teaching reading has been common in schools across New York for years. But the degree to which schools emphasize phonics has varied from district to district, even school to school.

Alyssa Colon-Garcia, executive director of English language arts for K-12 and early childhood education in Yonkers Public Schools, remembers reading instruction during the late 1990s that was supposed to be balanced, but lacked a focus on phonics.

"Sometimes there was a missing gap," Colon-Garcia said. She was helping students choose books they found interesting, but "what was absent was definitely that explicit instruction, especially when you're thinking about the phonics and building up fluency around what the student is reading."

In other words, the balance was off.

What is meant by 'the science of reading'?

Many who hail the science of reading take it for granted that the science points toward phonics instruction. But the term doesn't refer to a specific program or curriculum, or even an agreed-upon body of research. To some, the term is synonymous with phonics instruction.

In fact, educators in the Lower Hudson Valley say that decades of peer-reviewed research does not pit phonics against other reading approaches.

The terms science of reading and balanced literacy are often used as if they are in opposition, said Margaret Groninger, director of humanities for grades 4-12 in Mamaroneck. "They're really not."

Teachers have incorporated phonics even in balanced literacy or whole language classrooms. And the science of reading doesn't ignore comprehension.

The problem with the more balanced approach is when it doesn't consistently incorporate phonics, Coakley-Fields said.

"I think what's happened in the last year, year and a half, is it's become this idea that we've done it all wrong and there's this thing called the science of reading and if we can only just have that then all kids will learn how to read successfully on schedule," Groninger said. But, it's "obviously much more complex."

So what does the research show?

In the simplest terms, Coakley-Fields said, it shows children learning to read need both decoding and language comprehension to be skilled readers. It's not an either/or proposition, as some may believe.

She and several other educators referenced Scarborough's Reading Rope, created by Hollis Scarborough, a New Haven-based literacy expert, to explain the different facets of reading. The rope illustrates how two main strands, word recognition — which includes phonics — and language comprehension, work together in reading instruction, with each strand made up of smaller strands.

Strands within the word recognition rope include: recognizing the connection between letters and sounds; recognizing sounds that make up words; and recognizing words on sight.

Strands within the language comprehension rope include: having a strong vocabulary; understanding sentence structure; and understanding what a text says.

Research on reading points to six major pillars, only one of which is phonics, said Colon-Garcia. The others are: vocabulary, comprehension, fluency, oral language (being able to speak and listen), and phonemic awareness (hearing and understanding spoken words).

So research actually shows, said Jessica Brandel, a K-5 instructional coach in the Briarcliff Manor, that explicitly teaching kids about the structure of language is best.

Where does New York stand?

The state Education Department, which reports to the Board of Regents rather than the governor, has generally supported a focus on research-based practices for teaching reading, without endorsing a particular approach.

Education Commissioner Betty Rosa, in a statement released by Hochul's office, said that educators who use evidence-based teaching methods "provide a comprehensive approach that enhances literacy skills and equips learners with the tools needed for effective communication and lifelong learning."

Before endorsing Hochul's call for new requirements to teach phonics, though, the Education Department will await more details, department spokesperson Keshia Clukey said.

In response to questions about the Education Department's position on the science of reading and whether SED has the power to require it in schools, Clukey said the department creates learning standards that outline what students should learn and do. But curriculum decisions are up to local school boards so they can address their district's specific needs, she said.

Though Clukey wouldn't specifically say SED supports the science of reading, she said SED is committed to making sure teachers employ "evidence-based practices aligned with research about how students learn to read."

In October, the Education Department announced a partnership with the Hunt Institute "to transform early literacy instruction in New York State by embedding the science of reading into educator preparation." In a statement, Rosa said the partnership would ensure teachers "have the research-based tools and supports to bring the science of reading to life in their classrooms."

The news release also included a comment from state Assemblymember Jo Ann Simon, who said the literacy rate for kids in New York was "at a crisis level."

Clukey said SED is working to provide new literacy resources for schools.

"Together, early identification and early intervention can help educators to identify the specific supports that will meet the unique needs of each student," she said. "This may include targeted assistance. That is, research-based, specific reading instruction within a multi-tiered system of supports-integrated framework. These interventions need to be evidence-based and include the core principles of structured literacy and the Science of Reading."

Contact Diana Dombrowski at ddombrowski@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter at @domdomdiana.

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: NY schools teaching phonics, science of reading wanted by Hochul