Holland Taylor brings the late Texas Gov. Ann Richards' story to the stage one last time

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The name may take a minute to place, but point out Holland Taylor to anyone with discernment and acclaim is sure to follow. Lately, there's been plenty of opportunity to gush.

Taylor, who won a 1999 Emmy Award for playing a sexually forthright judge on the ABC series “The Practice,” has been thriving in this era of streaming television. In just the last year, she has stolen scenes as an old-guard feminist English professor who refuses to go gently into forced retirement on Netflix’s “The Chair” and as the network's unflappable chairwoman of the board on the second season of Apple TV+’s “The Morning Show."

A stage actress by temperament and training who found greater opportunities in television, Taylor is back in the theater these days, reprising her Tony-nominated performance as the late Texas governor Ann Richards. “Ann,” a one-person play she felt compelled to write, has its official opening at the Pasadena Playhouse on March 26. This West Coast premiere is the last time Taylor plans to perform the show.

Richards, a red-state Democrat with a folksy manner and a ready wisecrack, seemed made for television, as anyone familiar with her political speeches or occasional sit-downs with talk-show host Larry King can attest. For many, she was a voice of reason in a sea of partisan insanity. Her stylish crop of white hair announced the arrival of humorous common sense, a precious American resource that has been in limited supply since her death in 2006.

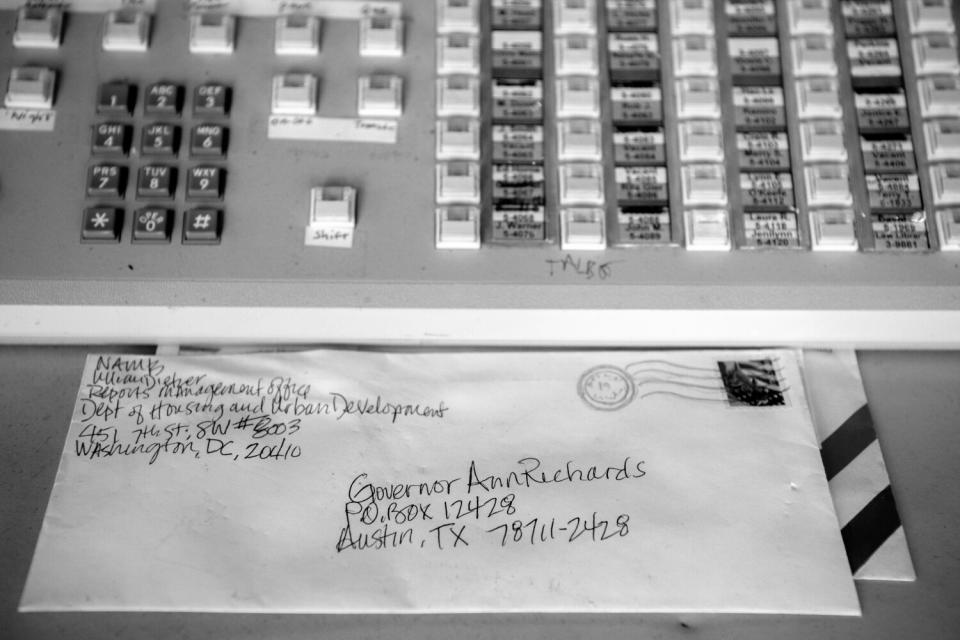

Speaking on a rehearsal break in the Playhouse's handsome library, Taylor acknowledges that it’s a good time to hear from Richards. Since “Ann” had its Broadway debut at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater in 2013, the world has seemingly gone to hell in a handbasket, suffering the twice-impeached presidency of Donald Trump, a deadly pandemic, an insurrection, and now a hot war in Europe.

It’s hard not to wonder what Richards would have made of this embarrassment of calamities or the recent alarming developments in her home state of Texas under a governor who never met a wedge issue he didn’t want to electorally exploit.

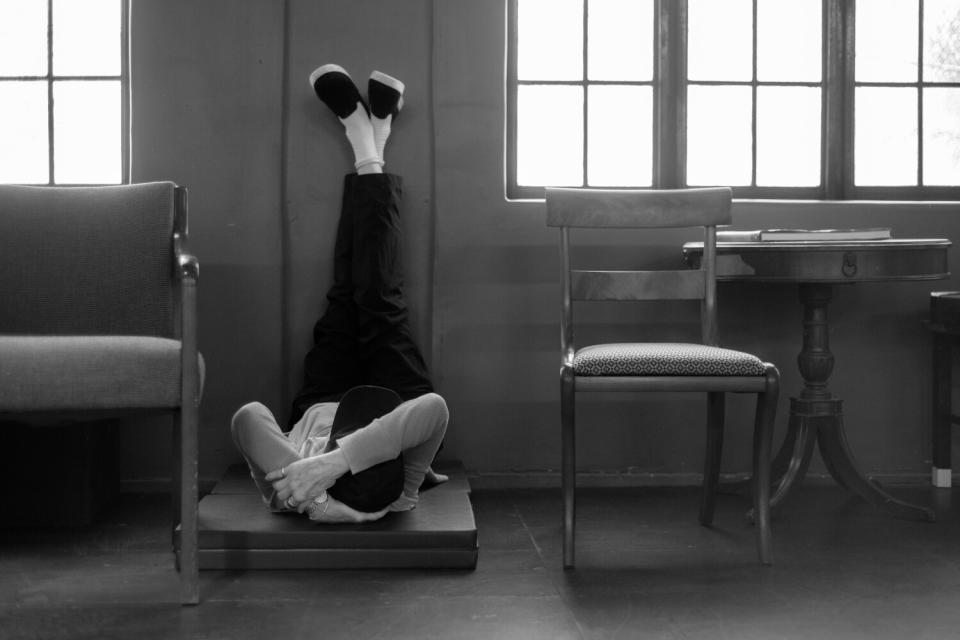

"Ann was very realistic," Taylor says. "She was like a general in the way she took in reality. I assure you she would be able to look coldly at everything that’s happening and say the disintegration of this, that and the other thing probably brought this about. Whereas I’m getting into bed and pulling the covers over my head.”

It’s remarkable the way Taylor drops into Richards' central Texas accent when speaking about her, as though she’s suddenly become possessed by the Lone Star icon. Taylor is not a mystical woo-woo type but talking about “Ann” brings out the latent Shirley MacLaine in her.

“I am not superstitious,” she says. “And I’m not particularly spiritual either. Except in this instance, I think I was drafted.”

Taylor looks vaguely heavenward as she says this. She has no other explanation. She had never written a play before, and she knows that she and Richards come from different worlds.

Born in Philadelphia and educated at Bennington College, Taylor has excelled at playing characters with a certain sandpapery sangfroid. But she shares Richards' passion for equality as well as her indefatigable work ethic.

She did her homework. After years of extensive research, she told herself she'd better start writing or she wouldn’t be ambulatory when it came time to perform the play, which tells the story of Richards' political rise while giving us a glimpse of the governor breathlessly at work to restore faith in democracy.

“Once I started creating the world, stuff would come to me that, I swear to God, I had a back channel,” she says. "I’m no Ann Richards, but I get her for some reason."

Taylor remembers her one meeting with Richards vividly. “I had lunch with her and [gossip columnist] Liz Smith, who was her great old friend from Texas. This was long before I was interested in playing her. I was so excited when I met her, I hardly knew what to do with myself. We were already at the table at Le Cirque when she walked in with that shock of white hair. Heads snapped. She might as well have been Mick Jagger.”

When Richards died, Taylor was devastated. “She was young, only 73,” she says. “I just thought she’d always be there, like that favorite aunt who gives you faith in the world. It struck me after a while that what was happening was unnatural, because I didn’t really know her. That’s when it came to me that I wanted to do something creative, because I was overwhelmed with so much feeling. If I were a religious person, I absolutely would have said that I was called by the heavenly angels to do this. But not being religious, I can still say it. Because how did this happen? People don’t decide they’re going to write a play and research it for three years when they’re in their 60s."

Nor do they typically opt not to renew their contract on a blockbuster sitcom so that they can pursue a project they're uncertain of realizing. Taylor was a regular on "Two and a Half Men" when the desire to write "Ann" seized hold of her.

"The show was a juggernaut hit," she recalls. "By the sixth year, when your contract ends, everybody assumes you're going to stay. And I did stay, but only as a visiting person. I was already focused on 'Ann,' which became my be-all and end-all, so I did not reup."

Taylor was driven to honor "a public servant who was in it for all the right reasons — to make people's lives better." But in creating the play, she also gave herself something long overdue — a Broadway role commensurate with her gifts.

Singlehandedly delivering this tour de force takes every ounce of her strength. After the New York run, Center Theatre Group was interested, but Taylor said she was too depleted to "walk across to Starbucks, much less to cross the stage of the Ahmanson."

The theater was Taylor's primary focus when she moved to New York after college. "I had no ambition to do movies," she says. "I didn't think I had the looks, but I wasn’t really even thinking of it. I read theatrical biographies when I was young, of Katharine Cornell and Eleonora Duse. I read about the theater life and fell in love with its traditions, the backstage society, the going out afterwards to your favorite boîte for a drink."

She was an experienced working actor before she studied acting in earnest with the one and only Stella Adler, Marlon Brando's teacher. "I was stunned, because I took some classes at her studio and saw that this woman really had a technique," she says. "She also had an extraordinary personality, the kind of personality that leaves such a dent on you. When they say something, it's forever."

It was Adler who encouraged Taylor to take the role on the sitcom "Bosom Buddies" that changed the trajectory of her career. "She told me that to be hired in the theater now — we're talking 1979, 1980 — you have to have a national name," Taylor recollects. "People want TV names, and that I should take the job and get known."

She temporarily settled in L.A. until, before she knew it, the city became her home and TV her main line of work. She has continued to do theater, but Hollywood has been a jealous taskmaster.

A jobbing actor of the most distinguished caliber, Taylor harks back to the modesty of her stage beginnings: "I didn’t have a big agent back in those days. I didn't come out of Juilliard or Yale. I stumbled into New York without knowing a soul, and without having a dime. I tell a lie. I had $2,000. And I stumbled along without any guidance into this or that job."

When Taylor won her Emmy for playing Judge Roberta Kittleson on "The Practice" in 1999, she walked up to the podium, lifted an eyebrow and, with an ironic wave of her hand, broke the audience up with one word: "Overnight!" Her success, of course, has been anything but.

Riding high at 79, she's finally able to pick and choose her projects. "There's so much work happening in television that actors have a chance to be in essentially a repertory situation, where they can play three or four quite different parts in one year and really build something."

She and her partner, Sarah Paulson, represent the best in class of this new acting era. Do they share trade secrets at dinner or swap intelligence on Ryan Murphy projects before bedtime?

"We don't talk about how we do what we do, but we'll admire some particular moment in each other's work that was unbelievably smart or touching or unique," she says. "I can tell you that she surpassed my highest expectation of her as Linda Tripp [in the FX series "Impeachment: American Crime Story"]. "I am still staggered by that performance. Every second counted. There was not a moment that wasn’t intentional, that wasn't filled with art and poetry."

When I praise the flawlessness of her performance as Professor Joan Hambling on "The Chair," Taylor beams with gratitude. "I love when I get the chance to play not a default Holland Taylor role," she says. "I’ve been so often cast as chilly, brainy, rich, mean, superior. First of all, I'm none of those things. But it's just so boring to always be cast that way, so when someone sees me another way I’m just thrilled."

Taylor found Joan, a Chaucer specialist who's been fighting against the patriarchy her entire career, especially exhilarating to play for her lack of vanity: "She doesn't touch comb to hair. She's an old lady who wears lipstick because that's the last thing to go. It was so incredible to be on a television show with a naked face. But holy God, when I saw how I looked!"

In person, Taylor's wit and matter-of-fact intelligence radiate warmth. She listens, one of the qualities that separates first-rate actors, even when she's not on set.

Relearning the script for "Ann" has been a Herculean task. This Pasadena Playhouse production was scheduled to take place in spring 2020. Taylor was memorizing the role when the COVID-19 pandemic forced theaters to close. She's understandably nervous about performing onstage again.

"I had held up Patti LuPone, who's a friend," she says. "She's playing in 'Company' now in New York. I went to the opening, and I thought, 'Patti’s staying safe.' Then she got COVID. I cannot get it, because no one can go on for me. The theater would suffer. And yet how can I necessarily save myself from it, if she couldn’t? It feels like a roll of the dice."

Bringing back Ann Richards is worth the risk for her. "In the past two years of this pandemic, I have thought what an image she is for the belief that there is goodness in leadership," she says. "Ann was of the point of view that leaders will come. Whenever anyone complained about the awful state of politics, she'd say, 'Quit that whining. Somebody's going to come, someone who's a real leader.'"

Taylor, inspired from above, slides into Richards' Texas drawl as though it were the sound of hope itself.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.