Homebound and scared in the coronavirus outbreak? This podcast helps me face my fears

The podcast I've been listening to lately isn't exactly light entertainment. It can be funny but it dives deep fast. It grabs my coronavirus-jumpy attention.

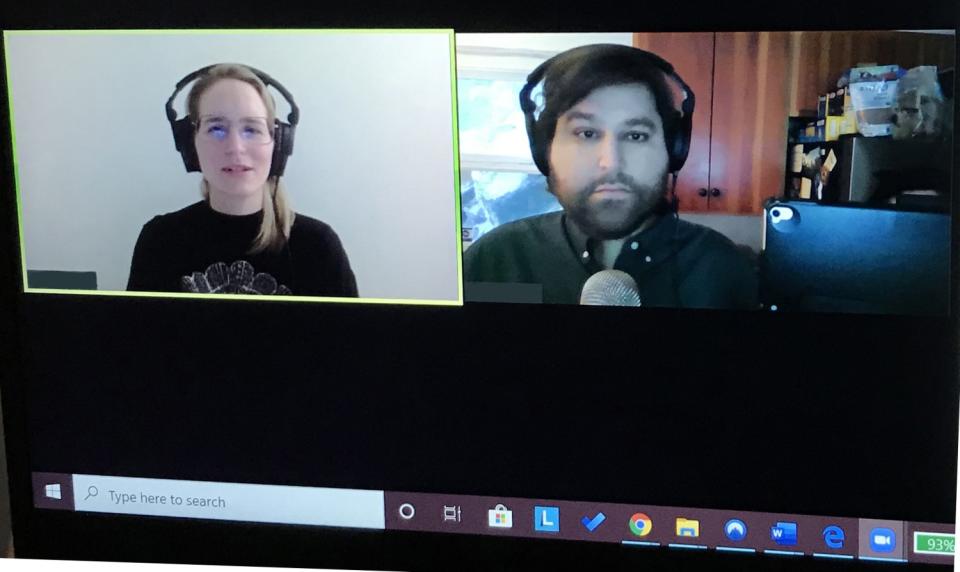

In the midst of a pandemic, two talented writers on opposite sides of our shuttered country speak to each other intimately. They cut right to the emotional quick.

How can we come to terms with not knowing how this pandemic story will end? How can we be real and not just say, "We're all going to be fine"?

The hosts of "Recoup" are still pretty young, but they have been through wars — and they're very familiar with the isolated, twitchy territory most of us have just entered.

Eva Hagberg, who lives in New York, had a brain hemorrhage at 31 and numerous serious health crises since have made her repeatedly "pop out of society."

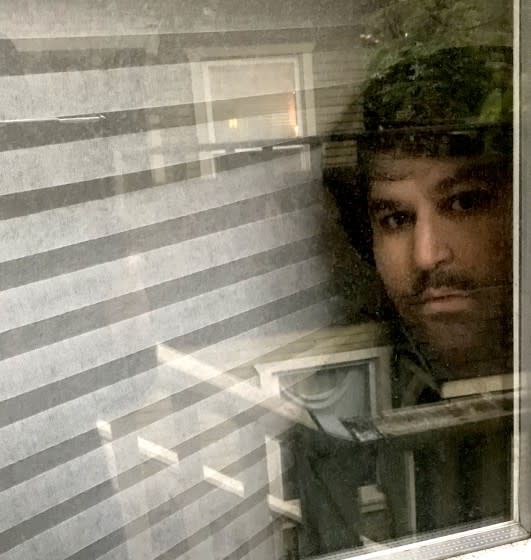

Adam Baer, who lives in Los Angeles, was diagnosed as a teenager with the first of a string of cancers and rare genetic diseases. For the past five years, Baer's been more or less homebound, except for doctor's appointments. It's hard for him even to get to them because he can stand or lie down but he can no longer sit.

Baer and Hagberg have spent so much time out of sync with others, knowing a lot of life was whooshing by all around them, without them. They've learned how to be comfortable with frequently being alone. They've learned how to find their own rhythms for getting through each day. They've learned to sit with terror and uncertainty while those around them say, "I can't imagine what you're going through," and mostly don't bother to try.

Now suddenly, we're all shut in and scared and bereft of the noise of life. We're novices. They are old hands.

"I feel like I finally fit in," Baer says.

"Your time has come, right?" Hagberg replies.

Their hope is to offer the rest of us access to their hard-earned tool kit. I soak up their coping strategies. I collect them like I'm gathering twigs in the woods to help me light a fire when I need to stay warm.

Uncertainty is hard. It's keeping me up nights. Baer and Hagberg have found ways of facing the unknowable that I find particularly comforting. I won't necessarily remember who said which thing when, but I know I will remember what helped me.

Hagberg describes a delicious cake she's ordered for herself. Each day, she's eating a slice. Will she be able to get the same cake again? It depends on whether the place she got it from stays open.

As people, we adapt to the unknown, she says, expanding our "window of tolerance day by day and finding the things that are certain. Like the cake that I ordered is delicious. That is a certainty. I don't know when I’ll have it again. So I’ll really enjoy it."

Baer says that after years of MRIs and tests, he's learned more or less to surrender to not knowing what will happen next.

"It's surfing. It's floating. It's like everything that somebody has said in a movie from the '90s." he says, laughing. "We don't know what's going to happen and we have to become OK with that. And yes, it's a hard transition for so many people."

Baer is the one who first tells me to try the podcast. It takes me a while to make the time to sit down and tune in. It is only after I have done so, when he and I speak on the phone, that I learn that he and his cohost have never met in person. They grew friendly years ago on social media. They found they had a lot of common ground.

This is another thing they've learned through their circumstances to be good at: cutting through the static and getting to the heart of things with people even when they can't be with them in person.

On the podcast, Baer describes his usual prepandemic routine of talking by phone to friends and relatives on their commutes when they are traveling between home and work. At home, he could make room for them most anytime. Their schedules were more rigid.

Both see good in the more meaningful long-distance connecting that a lot of people are doing now.

"I just hope that it leads to a major resurgence in active, very long phone conversations," Baer says.

"I'm with you," Hagberg replies.

He and Hagberg discuss the wider world's struggle with new stay-at-home rhythms, the initial crazed effort to stay perpetually productive and busy even when so much has changed. Hagberg says it's as if they've just transferred the work pressures home. But over time, people probably will adjust, they say, and learn to become less frenetic.

They may also come to see clearly, they say, that you don't have to be present at a workplace to do plenty of work well. It's an argument that Baer has been making passionately for a long time — one that has often been ignored. He hasn't been able to finish a master's degree in creative writing because of a residency requirement he can't fulfill. He's been rejected for staff jobs on similar grounds. Maybe this kind of bias will fall away too.

I listen and am soothed to hear the good along with the bad. Baer is happy his wife is working mostly from home now. He gets to see her more. He's alone less. He tells me later that he so rarely is able to be with his family on the East Coast so it's especially lovely for him to get to join in a Passover seder held on Zoom because everyone else is now in his boat too.

In the most recent episode of the podcast, Hagberg wasn't present. Baer spoke with his wife, Lina D'Orazio, a USC neuropsychologist and clinical psychologist, in part about their changed life, together at home.

Only later did I learn that Hagberg was absent because she had the virus, which in the end provided the biggest comfort of all.

I spoke with her on the phone. She'd survived a brain hemorrhage. She'd survived this, too, in her apartment, even though she'd had some really rough days. She thought at one point that if an ambulance arrived, she'd send it away because she wouldn't want to move. Still, she'd come out the other side.

It reminded me of one of my favorite moments in the podcast so far, when Hagberg describes how she used to be scared to confront her darkest fears. When her brain began misbehaving seven years ago, she just wanted to hear that she would be OK. Then a friend of hers who had terminal cancer told her that maybe she wouldn't be OK, but that learning that would not be the end.

"I thought that was the last house on the block, but actually there’s this whole neighborhood and that’s a neighborhood that you and I have moved into," she tells Baer. "We’ve been living out here on the edge of the abyss having a picnic … fully inhabiting this world of the unknown."

"But let's not call it an abyss, right?" he replies. "Let's just say there is no abyss. Somehow everybody thinks there is one, but they're wrong."

"Yeah, there's actually just more," Hagberg says.

Life changes. It sometimes gets scary. You figure it out as it comes.