Honestly, Sam Bankman-Fried Was Very Annoying From the Stand

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Slate’s daily coverage of the intricacies and intrigues of the Sam Bankman-Fried trial, from the consequential to the absurd. Sign up for the Slatest to get our latest updates on the trial and the state of the tech industry—and the rest of the day’s top stories—and support our work when you join Slate Plus.

At first, Thursday seemed as if it would be a monumental installment of this fall’s hottest tech drama, The United States v. Samuel Bankman-Fried. The trial was resuming after a weeklong recess, the prosecution was planning to introduce its last witnesses and rest its case, the defense was set to unveil its grand plan, and Sam Bankman-Fried himself was really, actually going to testify. The hype was so intense that by the time I got to the Southern District of New York early—like, really early—Thursday morning, 38 of my fellow reporters/crypto analysts/SBF obsessives had beat me to the premises; more than a few had arrived before 4 a.m. I had snoozed, and I had lost: Not only did I not snag a seat in the actual courtroom, but the media-overflow room was the most packed it’s been the entire trial. (Among the attendees I spotted? Michael Lewis.)

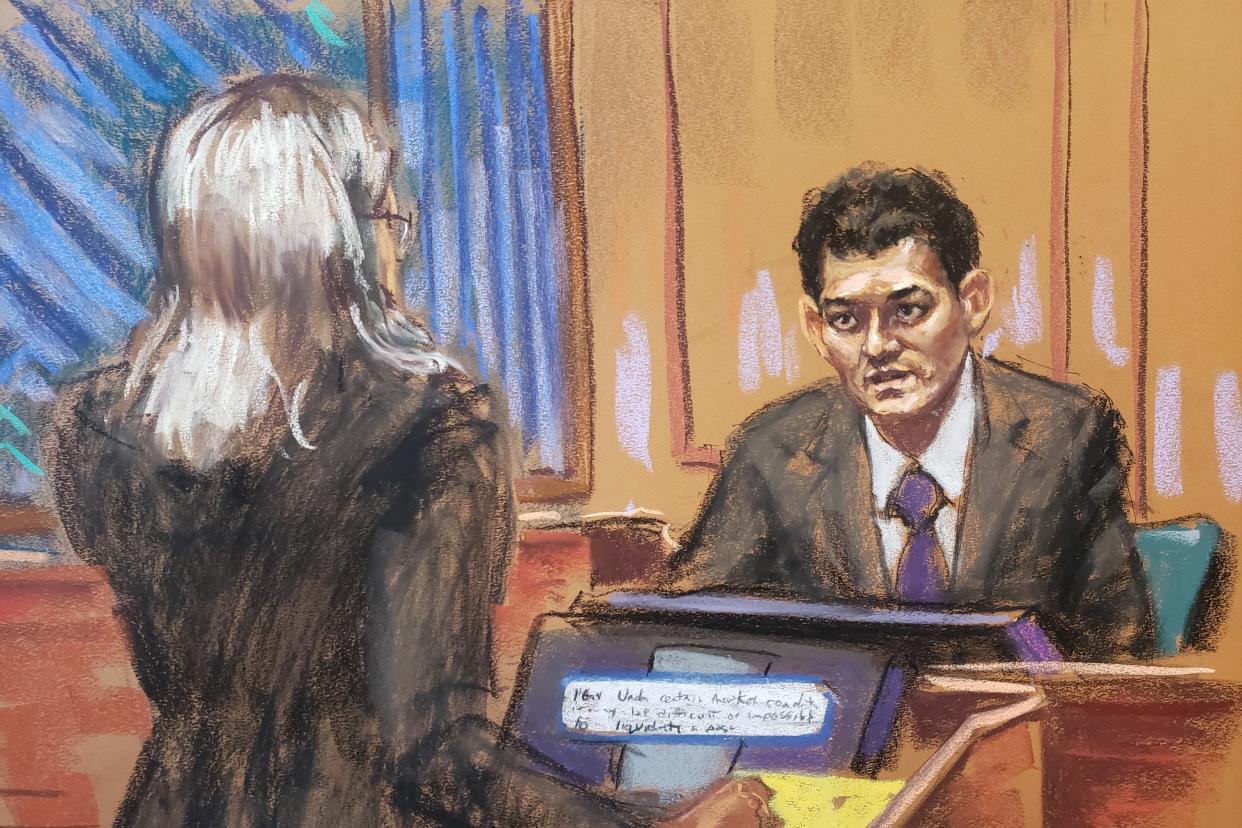

Here’s what you should know upfront: SBF did speak from the stand on Thursday, under oath, but none of his words reached the tired ears of the jury. The real action will occur on Friday, when SBF may finally testify for the jurors’ benefit.

What happened Thursday? The court did get back to business, and the prosecution did rest its case, bringing on just one final witness—Marc Troiano, an FBI special agent specializing in corporate commodities and securities fraud. Troiano went over his retrieval of damning, undeleted Signal chat messages from Gary Wang’s laptop and Caroline Ellison’s phone. This was mostly to show that this evidence had been obtained in a sound manner.

Now the defense’s turn. It ushered in Krystal Rolle, a Bahamian attorney who’d advised SBF when regulators came a-callin’. After FTX’s bankruptcy, Rolle had accompanied SBF to and from his meetings with the Bahamas Securities Commission, joined by a group that included the defendant’s father, Joseph Bankman. This led to an understated defense point that Wang’s prior testimony about how SBF directed him to keep transferring FTX assets to Bahamas regulators, instead of to the United States, missed a key factor: that the former CEO was served a Bahamas Supreme Court order regarding FTX assets, as Rolle confirmed. Had he disobeyed, he would’ve been subject to contempt of court and/or imprisonment. Fair enough (though SBF ended up getting jailed there anyway). The prosecution then made a subtle dig at another one of the defense’s main implications—that the government had all but coached its witnesses into saying certain things to support its case. “There’s nothing irregular about meeting with lawyers in advance of testifying, right?” asked Assistant U.S. Attorney Nicolas Roos. Multiple objections from the defense didn’t prevent Rolle from proffering her answer: “Absolutely not, no.” She was soon dismissed.

Up stepped Joseph Pimbley, a longtime financial consultant fluent in physics, software code, mathematics, and quant trades—kinda like SBF and his friends. At the defense’s request, Pimbley yanked out data from FTX’s code base on Amazon Web Services, covering the lines of credit afforded to entities under Alameda Research (FTX’s sister hedge fund), FTX’s total customer-only assets, and the percentages of users who’d opted in to spot trading, margin trading, or futures trading on FTX. The veteran analyst put up custom-made charts to show 1) how Alameda’s line of credit on FTX increased from October 2021 through November 2022; 2) the customer-exclusive balances on the platform; and 3) the shares of users who’d voluntarily put up for spot and margin and futures trading. That final graph appeared to demonstrate that a lot of FTX vendors had in fact agreed to put up their deposits as collateral for other traders—although, as the prosecution later tried to point out, the relevant terms for futures trading were different from those for spot and spot margin trading. Not the most representative sample of FTX users who were ostensibly fine with SBF splurging their money on ginormous political donations and various other things.

Pimbley offered a dry, technically proficient, ultimately narrow story, explaining that he had done just what he was told to do, and didn’t know much else about the case except for what he’d gleaned from “headlines.” The prosecution did clarify that Pimbley’s numbers were an incomplete picture, through no fault of his own, thanks to wackadoodle accounting from FTX that left out many important disclosures. The complexity, though, made it hard for the prosecution to hammer in the points it wished to without repeating questions about the charts. This culminated, shortly before Pimbley left, in a spontaneous, vivid story from Judge Lewis Kaplan:

You know, when I was a kid, I worked in my father’s deli, and if he gave me the assignment to go add up the column that showed how many pounds of smoked fish we sold last month and I gave him a number, it means pastrami is not included; neither is coleslaw or macaroni salad. We can keep on going through everything in the deli. But we’re not taking the time to do that.

The conclusion: Stop asking the poor witness about what his analysis is missing and get on with it. It wouldn’t be the only time the judge carried out “the full Kaplan.”

OK, but you wanna know about the full SBF. Here’s what happened.

After the lunch break, Bankman-Fried preemptively sat himself in the witness box, smirking and shifting back and forth in his chair before getting pulled away—he hadn’t been formally summoned. Then, the eager crowd learned we wouldn’t be getting admissible testimony from Bankman-Fried yet. Instead, we would settle an ongoing dispute between the prosecution and the defense over what testimony from SBF could be presented to the jury. We still don’t have an answer to that. But we did hear what arguments were at play, as well as what SBF would sound like when put under prosecutorial duress. Spoiler: It ain’t that different from how he sounded under journalistic duress. Except his answers were even more crazy-making.

The topics revolved around the defendant’s secretive workplace communications, his conversations with lawyers preceding the collapse of his companies, and whether/how/why SBF felt entitled to FTX customer funds. He sounded rather confident and straitlaced when responding to his attorneys’ questions, something that was jarring enough considering how long it’s been since we last heard from the guy. He spun out long-winded responses to the softballs—basically, all leading to the argument that SBF didn’t do anything wrong willingly, and was just going along with his counsel’s approval when it came to taking out personal loans, funneling FTX customer cash to Alameda’s North Dimension bank account, and deleting his group chats. Kaplan was not impressed, scolding lead SBF lawyer Mark Cohen after his queries over FTX’s document-retention policies and the role of corporate attorneys in dictating their terms: “This would be a lot more helpful to you if I was not getting just vague generalities about what he understood.” (Emphasis mine, but I’m willing to say under oath that I heard the italics in Kaplan’s voice.)

Bankman-Fried’s confidence receded just a bit during cross-examination. It wasn’t long after Assistant U.S. Attorney Danielle Sassoon took charge that we started hearing constant pauses (some much longer than others), plenty of “uhhhhs,” layers of caveats, and circular answers that recycled myriad stock phrases: A) “I don’t remember what was said contemporaneously,” B) “That may have happened,” C) “I’m not sure,” D) “I apologize,” E) “I wish I could tell you,” F) “I had conversations,” G) “I don’t have the policy in front of me,” H) “That is not how I would characterize it,” I) “[insert lawyer’s name here],” J) “I don’t specifically recall, but …”

An image long familiar to financial reporters manifested yet again: the once-powerful crypto wonder under fire. Let us now match each of the above replies with its respective question. (I’m paraphrasing.) Did you discuss your Signal use, your auto-deletion policy, and your transmission of business documents like balance-sheet drafts over the platform, even though your own policy seems to say you weren’t supposed to do that? (C, E, F, G, H, I, J.) What did you know about Alameda’s North Dimension account, and when? Who approved the transfer of customer funds? What was the formal arrangement? (A, C, H, I, J.) What did you understand from the FTX terms of service in all its incarnations? What did they say about safeguarding customer assets? What did you know about Alameda’s negative balance on FTX? Did you discuss your personal loans with your lawyers? (A, B, C, D, E, G, H, I, J.)

I really can’t convey this any more effectively: It was highly repetitive and very frustrating. The tropes were frequent enough that Kaplan quipped about them to Bankman-Fried: “I take it that the answer is you don’t remember. Is that about it?” Even Sassoon was visibly annoyed, explaining that SBF wasn’t giving direct answers. As Kaplan himself noted, “The witness has what I’ll call an interesting way of answering questions.” One telling moment saw SBF saying “I don’t recall” something, taking a sip of water, and then rushing to set his bottle down when Sassoon followed up, “What do you recall?”

Cohen was unhappy about how this was playing out for his client, and he complained to the judge that the government was going “beyond the mark” in needling SBF about whether and when he’d consulted his lawyers. “To each of the topics, Mr. Bankman-Fried testified that he consulted with counsel and he took comfort from those consultations, which is all we have ever taken as a position,” Cohen remarked. “We have never advanced the formal advice-of-counsel defense, as Your Honor knows.” Now it was Cohen’s turn to receive a Kaplan Hypothetical Monologue:

Kaplan: Let’s assume that somebody robs a bank, knocks over Walmart, whatever, and comes upon a large sum of illegally obtained money, and the person decides it might be a good idea to salt this away and make sure nobody is going to discover it. Do we agree that engaging in a transaction, an object of which is to conceal the source of the money, is money laundering?

Cohen: In Your Honor’s hypothetical, yes.

Kaplan: The next step is the guy says, “Let me figure out how to do this,” and he goes to a lawyer. He says to the lawyer, “I want to buy an expensive condo on Billionaires’ Row and I want to form a limited liability company, which we ought to call Gold Dust. I’ve got just the apartment and I’d like you to prepare a contract of sale.” The lawyer is not told where the money came from, not one word about what the objective is—to hide the money or the source. The lawyer incorporates the LLC, the lawyer prepares the contract of sale, the lawyer represents Gold Dust. Now the defendant is apprehended and charged with money laundering. And the defense is: “Well, I had a lawyer who organized the LLC. I had a lawyer who did the contract of sale. I had a lawyer at the closing. And I offer this as evidence that I didn’t have a criminal intent in hiding the money.” … How is that different from what you are trying to do, in principle?

Kaplan clarified, “I am not saying anything about your client’s guilt or innocence,” but the message seemed pretty clear. Anyway, this is why we don’t have a firm clue about what’s going to happen on Friday. Stay tuned!