We should honor this Japanese American biochemist interned during WWII in Sacramento | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On a June day in 1942, UC Berkeley President Robert Sproul spoke before the newest class of graduates. As the country had just entered World War II, the atmosphere was tinged with uncertainty about the future. When it came to announcing the class valedictorian, Sproul told the audience that the young man, Harvey Akio Itano, could not accept the award because “his country had called him elsewhere.”

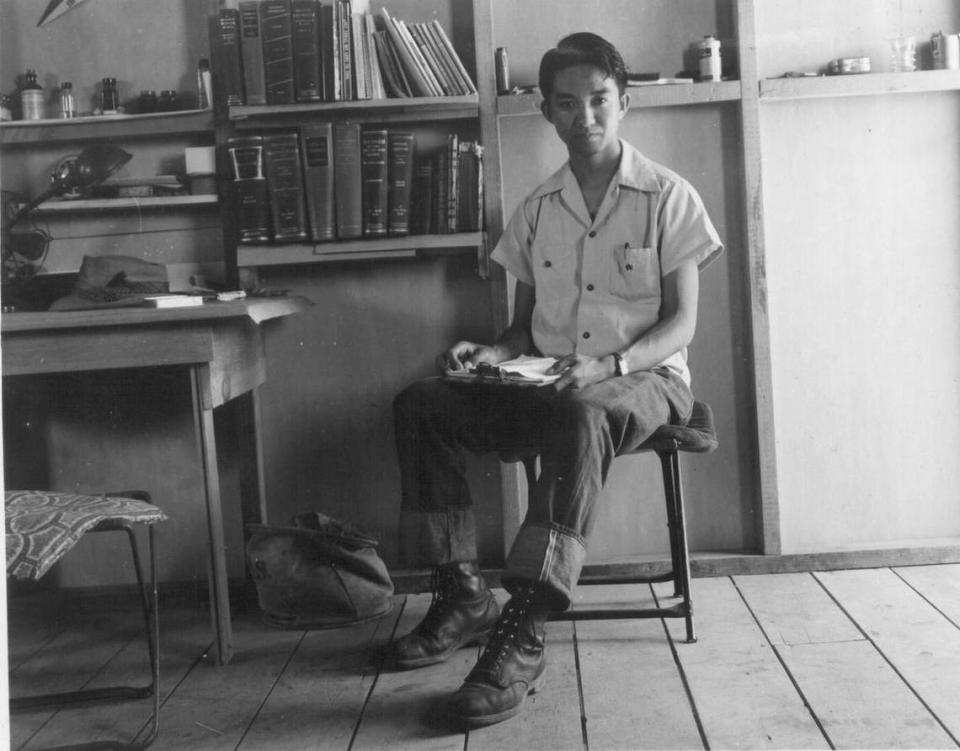

Elsewhere, however, meant an incarceration camp for Japanese Americans. While his classmates graduated, Itano was imprisoned at a U.S. Army assembly center in northeast Sacramento County (later called Camp Kohler).

Opinion

Feb. 19 marked the Day of Remembrance to honor Japanese Americans interned during World War II. We should also honor the legacy of Harvey Itano.

A Sacramento native, Itano was a pioneering scientist who made several major contributions to medicine working alongside Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling. Their greatest accomplishment, discovering the nature of sickle cell anemia, saved thousands of lives. For much of his career, Itano dedicated himself to working in public health as a researcher at the National Institute of Health and as a professor of medicine at UC San Diego.

Born on November 3, 1920, Itano grew up on N Street in Sacramento’s Japantown. After attending Sacramento High School, Itano went to UC Berkeley, where he majored in chemistry and served on the student health committee. In 1942, following President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, Itano and other Japanese Americans on the West Coast were sent to detention camps across the country. Shortly before UC Berkeley’s commencement, Itano joined his family at the Sacramento Assembly Center, and they were later sent to the Tule Lake camp in Northern California.

Even after arriving in camp, Itano received offers from several Midwestern universities to continue his studies. With help from President Sproul, the U.S. Army granted Itano permission to leave camp and enroll at St. Louis University Medical School in June of 1942. Itano became the first student to leave the camp, and soon thousands more followed him to universities across the Midwest and the East Coast.

At St. Louis University, Itano worked under Nobel Prize winner Edward Doisy. A biochemist who discovered Vitamin K, Doisy encouraged Itano to pursue biomedical research. With Doisy’s recommendation, Itano successfully applied to work with Pauling at the California Institute of Technology.

Pauling, who was already famous for his work on chemical bonds, worked closely with Itano on studying the proteins in blood. Through their research, they discovered the causes of sickle cell anemia using electrophoresis. Itano, Pauling and two co-authors published their findings in 1949, and their report influenced the field of molecular genetics. In 1954, Pauling received a Nobel Prize for his contributions to biochemistry. Even after leaving CalTech, Itano and Pauling remained close friends throughout their lives.

After graduating from Cal Tech with a PhD in chemistry, Itano spent the next 20 years continuing his research on sickle cell anemia at the National Institute of Health. His work on sickle cell anemia garnered widespread acclaim among Black Americans, as many members of the community were disproportionately affected. In 1972, Itano received the Martin Luther King, Jr. Award from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for his work on the disease.

In 1970, Itano left the National Institute of Health to become a professor of medicine at UC San Diego Medical School. In 1979, Itano became one of the first Asian Americans inducted into the National Academy of Sciences. He died on May 8, 2010, after a long struggle with Parkinson’s Disease.

Among the many heroes in Sacramento’s history, Itano should be remembered as one of them. Despite his country betraying him by incarcerating Japanese Americans like himself on the basis of race, Itano chose to give back to his country through his lifelong career in public health.

Jonathan van Harmelen is a PhD candidate in history at UC Santa Cruz. He is a columnist for the Japanese American National Museum’s blog Discover Nikkei. His latest book, “The Unknown Great,” is co-authored with Greg Robinson and is out with University of Washington Press.