Hooked on History: Twin City clay industry prospered in post-World War II era

When the New York stock market crashed in October 1929, it helped to spark the Great Depression. One of the first industries to suffer was the clay industry, which was dependent on construction and an expanding economy.

One after another, the clay plants in the Twin Cities closed down. Most were only able to operate sporadically during the 1930s.

Hundreds of workers in Uhrichsville and Dennison found themselves unemployed — with no prospective of finding jobs elsewhere.

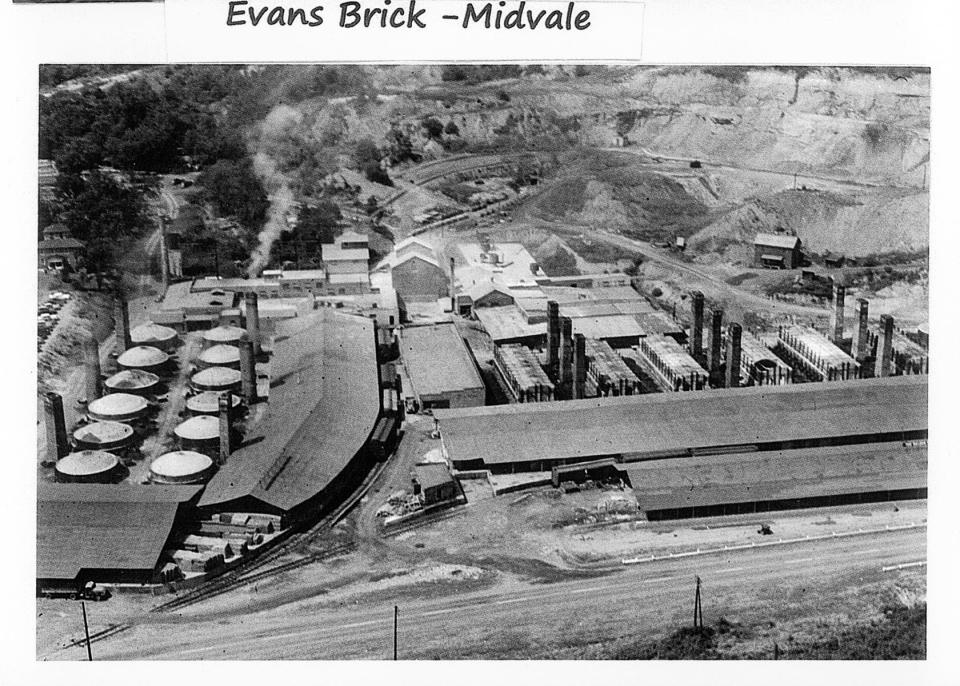

The late Milan “Mike” Borojevich Jr. of Uhrichsville recalled that his father, Milan Sr., who worked at the Royal plant near Midvale, was out of work for 50 months during the Depression. The Borojevich family lived in a company-owned home at the Royal Settlement next to the plant. They were allowed to continue living in the house without paying rent. But when Milan Sr. returned to work, the back rent was deducted from his pay a little at a time.

The local clay industry saw several changes during the late 1930s.

On Feb. 18, 1936, the McClave family, which had ties to the clay industry in Uhrichsville dating back to 1909, formed the Superior Clay Corp., one of the city’s enduring businesses.

The company started by purchasing the old Buckeye sewer pipe plant in Maple Grove west of town. Three years later, it bought the Wolf-Lanning plant east of Dennison. It was a bold move to purchase the shuttered plants in the midst of the Depression, but the McClave family succeeded.

Fires also plagued the industry.

In just 40 minutes, fire reduced to ruins the Stillwater Clay Products Co. plant on the Newport Road south of Uhrichsville on April 14, 1938. The fire started in the northwest corner of a building were the engine room was located. Defective wiring was suspected as the cause.

About 200 men were thrown out of work.

The company announced plans to rebuild, hoping to be back in operation within 60 to 90 days.

The Stillwater plant was back in operation by the time that Plant No. 1 of the Ross Clay Co. east of Dennison was destroyed by fire on May 12, 1939.

The blaze broke out shortly after 9 a.m. and quickly spread through the three-story factory building. A local paper said the building was transformed “into a huge, raging furnace which sent heavy clouds of black smoke into the sky which attracted several hundred spectators from Uhrichsville and Dennison whose automobiles jammed roads leading into the plant.”

The plant had been operating on a part-time basis, and company officials had planned to resume full-time production.

Plant No. 1 was never rebuilt. Ross Clay Products consolidated operations at its other plant in Lock Seventeen.

The clay industry began the postwar period in good shape. In July 1946, F.E. Gintz, manager of the New Philadelphia office of the United States Employment Service, reported that 2,550 people worked in the clay products industry in Tuscarawas County.

That June, the 12 sewer pipe plants in the county produced 32,000 tons of clay sewer pipe and were operating at 95% capacity. They were 7% above the production in June 1940.

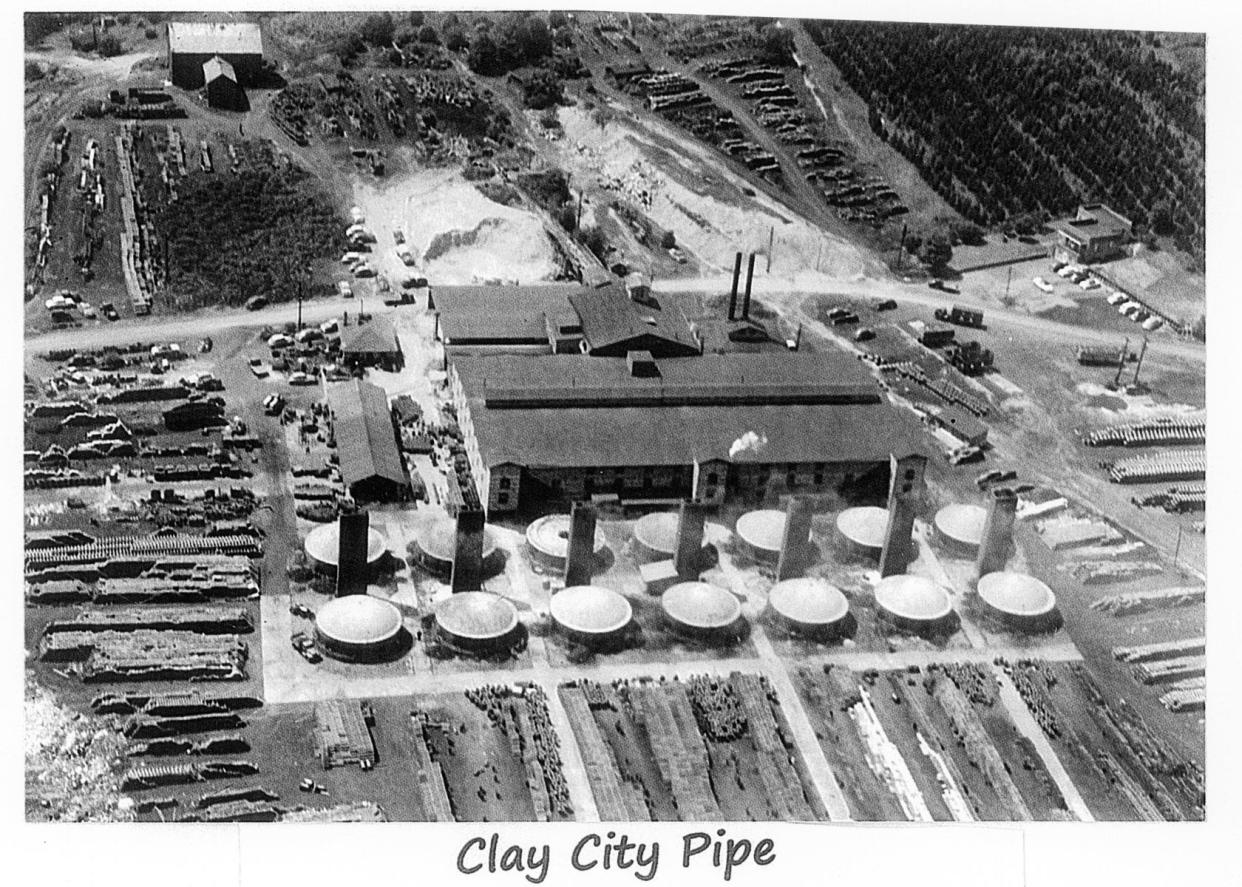

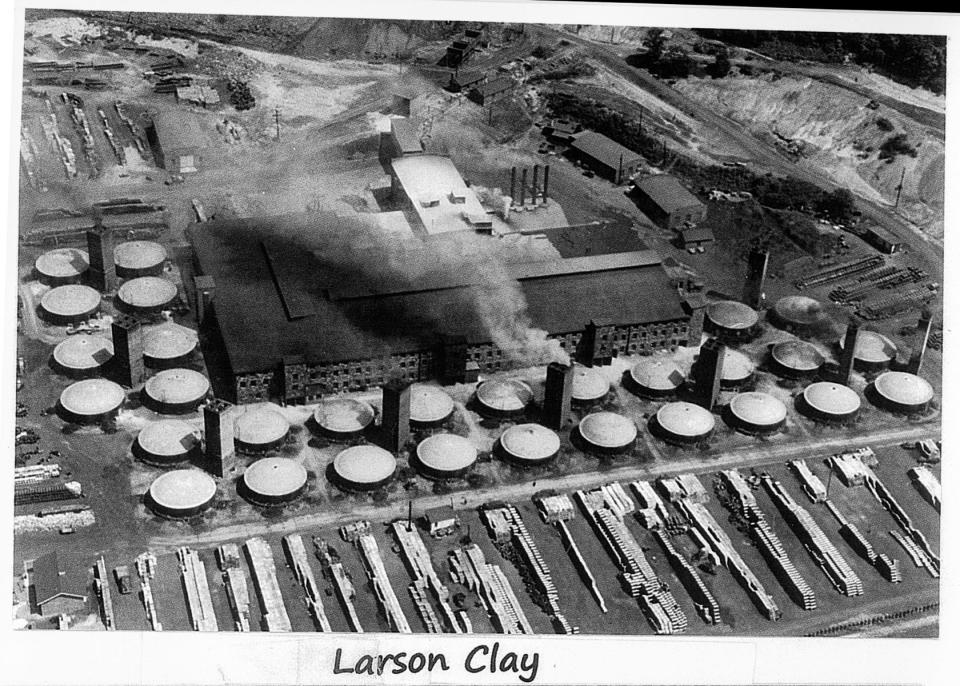

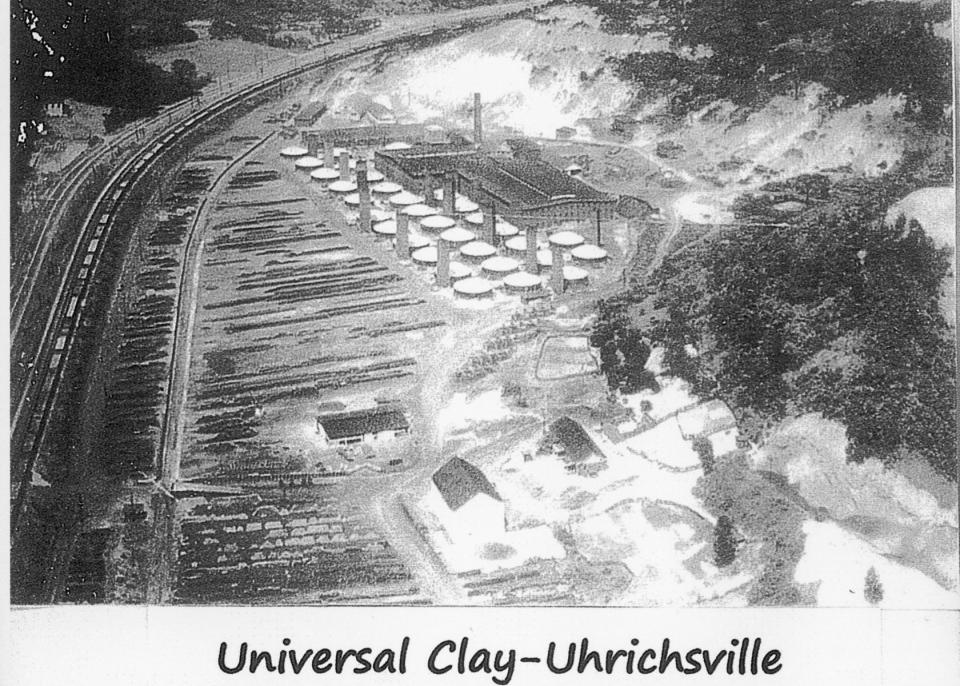

When the first National Clay Week was held in Uhrichsville in 1950, there were 32 plants in the county manufacturing sewer pipe, brick, or pottery out of clay. Local plants included Universal Sewer Pipe Corp., Evans Pipe Co., Larson Clay Pipe Co., Robinson and Sons Clay Product Co., American Vitrified Products Co., Stillwater Clay Products Co., Superior Clay Corp., Dennison Sewer Pipe Co., Belden Brick Co., Ross Clay Product Co., Robinson Clay Product Co., and the Clay City Pipe Co.

The Clay Week program that year noted optimistically, “What is the future of the clay industry? At the moment the industry ranks among the leaders, an industry which has grown tremendously in the past decade. And the end is hardly in sight. Clay research authorities are continually introducing new markets, markets which assure the industry of even greater success, financially and otherwise. What’s more, clay pipe is going to war if necessary and clay manufacturers are alerting themselves to their growing stature in the national defense program.”

In the Twin Cities, several generations of one family would find work in the clay plants.

The late Tom Heakin worked for Superior Clay Corp. from 1947 until he retired around 1989-90. His great-grandfather, James Caldwell, came to America from Scotland when he was in his 20s and eventually became the first superintendent of the Royal sewer pipe plant near Midvale. Heakin’s father, Harry, worked at the Wolf-Lanning plant east of Dennison as a molder and a brancher beginning in the 1930s. The elder Heakin made folk art out of clay, items such as piggy banks, dogs, ash trashes that looked like kittens, horses and frogs.

Heakin worked one summer at the Royal plant when he was 15. It was during World War II. “They would hire you off the street because they couldn’t get men,” he remembered.

As soon as Heakin graduated from Uhrichsville High School in 1947, he went to work at the Wolf-Lanning plant.

His first job was as a laborer. “I did a little bit of everything,” he said. “Later on I became an extra man in the drawing and setting crew.

“It was hot work. In the summer, you would just about wilt. In the winter, I used to get a job driving a tractor for the drawing crew. You couldn’t wait to get back inside.”

When he first worked at the plant, all of the kilns were fired with coal. “That’s when it got really hot,” he said. “But you could get warm in the winter.” In the 1960s, the plants in the area started using natural gas.

People in the two towns lived their lives around the clay plants. “People in town used to time their lunches by the whistles at the plants,” Heakin said, noting that the whistles sounded at 11 a.m.

The workers always had a dog at the Wolf-Lanning. Heakin remembered one in particular that was a part collie mix. When the whistle blew at the plant to signal lunchtime, the dog would make the rounds to beg for food from the workers. “The dog took care of itself, but we fed it good,” he said.

“One time, some guys stopped at the plant with two German shepherds,” he said. “The collie sent them whining back to the truck.”

Fire remained a persistent danger for the clay plants of the Twin Cities.

On June 9, 1956, a fire caused $500,000 in damages at the Clay City Pipe Co. plant near Newport. The main building at the plant — which was three stories high and covered 35,000 square feet (about 2 acres) — was destroyed in about an hour, along with an annex. The cause of the fire was undetermined.

Clay City was rebuilt at a cost of $2 million and reopened in March 1958. The Uhrichsville Evening Chronicle hailed it as one of the nation’s most modern clay products plants. By June 1958, 138 men worked there.

On Sept. 12, 1959, the nearby Stillwater Clay Products Co. plant was destroyed by fire. The loss was estimated at $750,000.

The fire was caused when a heating machine exploded, burning a worker on his leg and arm. The machine, a portable gas heating device, was being used on the third floor on the west side of the building.

The blaze destroyed virtually the entire plant, except for the office and the kilns.

The story of the Twin City clay industry will conclude in July.

Jon Baker is a reporter for The Times-Reporter and can be reached at jon.baker@timesreporter.com.

This article originally appeared on The Times-Reporter: History: Twin City clay industry prospered in post-World War II era