Hopes for end of drought hinge on spring rains

Cool, wet conditions throughout the winter and an above average snowpack in the western mountains hold the promise of bringing an end to one of the worst droughts in living memory, but whether Montana emerges from the historically dry soil moisture conditions that have plagued the state for the past three years still depends upon this spring rains. And at this point it’s just too early to early to tell if they will arrive at the time and in the quantity that is hoped for.

That was the message from Zach Hoylman, assistant state climatologist for Montana. During Thursday’s U.S. Climate and Drought Summary and Outlook presentation, Hoylman noted that while soil moisture conditions are certainly better today than they were a year ago, longstanding moisture deficits make it “nearly impossible” to forecast whether long-suffering farmers and cattlemen can bank on a return to the productive seasons they last saw in 2020

“That’s the million-dollar question right there,” Hoylman said of the uncertainty of forecasting the ag production year. “There’s certainly been improvement across Montana, and this year’s snowpack especially in the southwest and some of those tributaries going into the Missouri River are pretty good. That being said, there’s still longstanding moisture deficits across many portions of the state.”

“What we’ve learned over the last several years is the springtime recharge of soil moisture conditions are absolutely critical,” he continued. “Depending upon how much precipitation we get in April, May and June has a huge impact on soil moisture driving pasture and range conditions going into the summer. It’s going to be hard to say.”

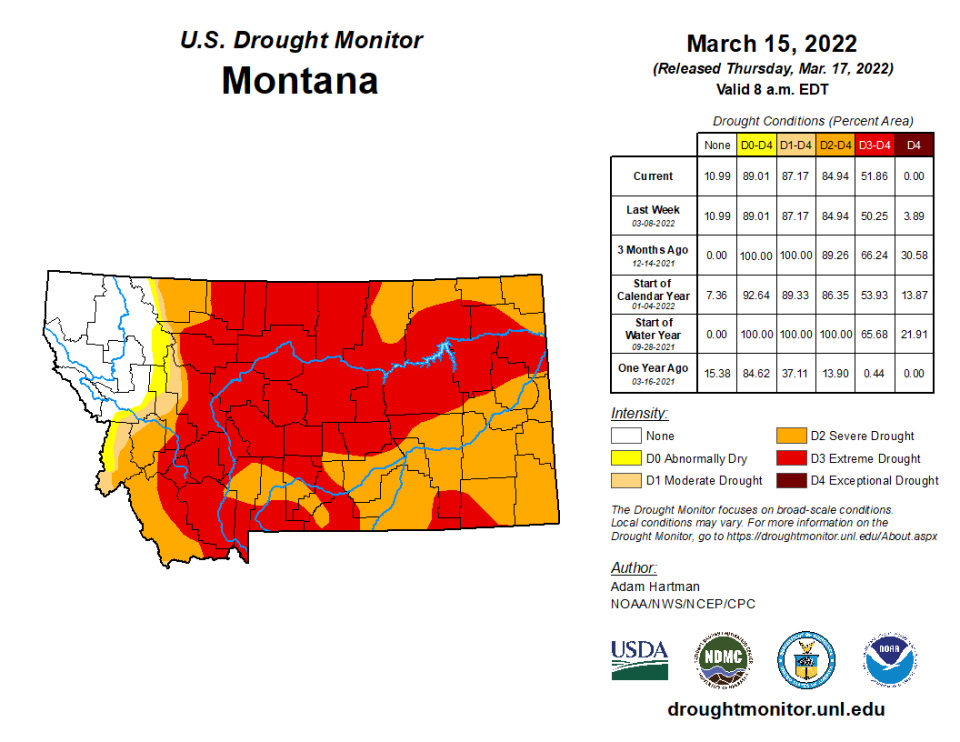

What can be said with certainty is that Montana is far better off today than it was a year ago. In March 2022, 85% of the state was reporting severe to extreme drought conditions. One year later, less than 20% of Montana’s fields, streams, rangeland, and pastures are experiencing the same level of drought, with most of those conditions concentrated along the Hi-line from Havre to the North Dakota border.

“It’s better than it was last year at this same time,” Hoylman acknowledged, “but we still didn’t see the recharge of soil moisture storage that we were hoping for last fall before the freeze up.”

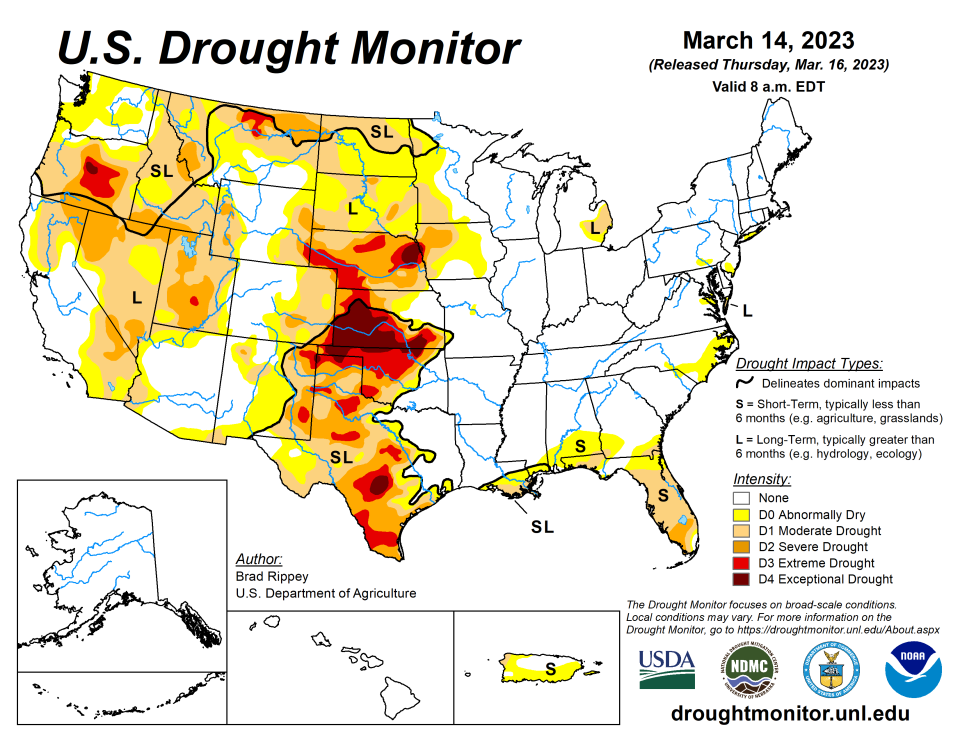

While the seasonal outlook remains positive for most of Montana the same cannot be said for other parts of the Midwest. Much of Nebraska and nearly all of Kansas remain under the pressure of extreme drought conditions, while Wisconsin and Minnesota remained buried under near record snowfall.

“The 2022-2023 winter has been one for the record books,” Hoylman noted.

“Drought remains a pervasive component of this landscape, especially in Kansas,” added Dennis Todey, executive director of the USDA’s Climate Hub in Ames, Iowa. According to the U.S. Drought Mitigation Center, the majority of the central region is classified as experiencing long-term with drought conditions.

In some places precipitation deficits are reflective of more than three years of drought. Extreme drought has appeared in portions of the central region since early 2020. We have a long way to go before this region is fully out of this multi-year drought.”

Some areas in Kansas received record-low annual precipitation totals during 2022 and have not received much, if any, cold-season drought relief. Besides damaged rangeland, pastures and poor crop conditions, the worst hit areas have been exposed to frequent dust storms with streams and ponds completely devoid of water.

Three-hundred miles to the north things could not be more different.

“It’s been exceptionally wet in the upper reaches of the Mississippi and along the western Great Lakes states,” Hoylman said. “In fact, according to NOAA, Wisconsin experienced the wettest winter period on record going back 128 years, and Minnesota experienced its second wettest winter.”

“At least a component of this moisture can be attributed to a series of atmospheric rivers that paraded through the United States this winter season starting from the California coast and moving all the way north and east to the Great Lakes region,” he added. “The extreme wetness that has been observed between December through February in the western Great Lakes states has continued into March.”

Snow has been on the ground in much of North Dakota and portions of the neighboring states since November, with recent cold weather maintaining impressive snow depths even as snow continues to fall. Bismarck, North Dakota, reported at least a trace of snow on 11 of the first 13 days of March, totaling 22.5 inches. All this leads to increased chances of flooding as the weather begins to warm.

“According to the National Weather Service flood risk along the mainstem Mississippi River from the Twin Cities area down through about Keokuk, Iowa (near the Missouri/Illinois border) is well above normal,” said Hoylman. “There are enhanced chances of major flooding that will occur along the mainstem of the Mississippi in many locations.”

“Flooding is not expected across the upper reaches of the Missouri River; however, the mainstem of the Missouri is likely to experience episodic floods from about Nebraska City downstream to the mouth of the river (at St. Louis).

“All of this not a forgone conclusion,” Todey added. “It matters on how the snow comes off. The later we go into the season, the later we hold on to a snowpack, the more likelihood there is for a fast warm up. We’ve seen that many a time. We like to see it slowly melt away. The risk of that not happening increases with time as we get later into the warm season.”

“We have a ton of water that’s going to produce potential flooding, but a lot of this has fallen on top of frozen soils,” Todey continued. “A lot of that water is going to run off and go someplace else and not enter the soil profile. Despite all that snowfall we’re still going to have some relatively dry soils that are not going to be fixed by that snowfall. We’re still going to need some more rains after the snow melts.”

This article originally appeared on Great Falls Tribune: A cool, wet winter raises hopes Montana drought is at its end