How Donald Trump took over the World Bank

WASHINGTON — Though its headquarters are only two blocks from the White House, the World Bank managed to stay almost entirely out of President Trump’s view for the first two years of his administration, even as he continued to rail against other transnational arrangements, such as the United Nations and NATO.

But that changed in January when the unexpected departure of World Bank President Jim Yong Kim gave Trump the opportunity to remake the institution with his own pick.

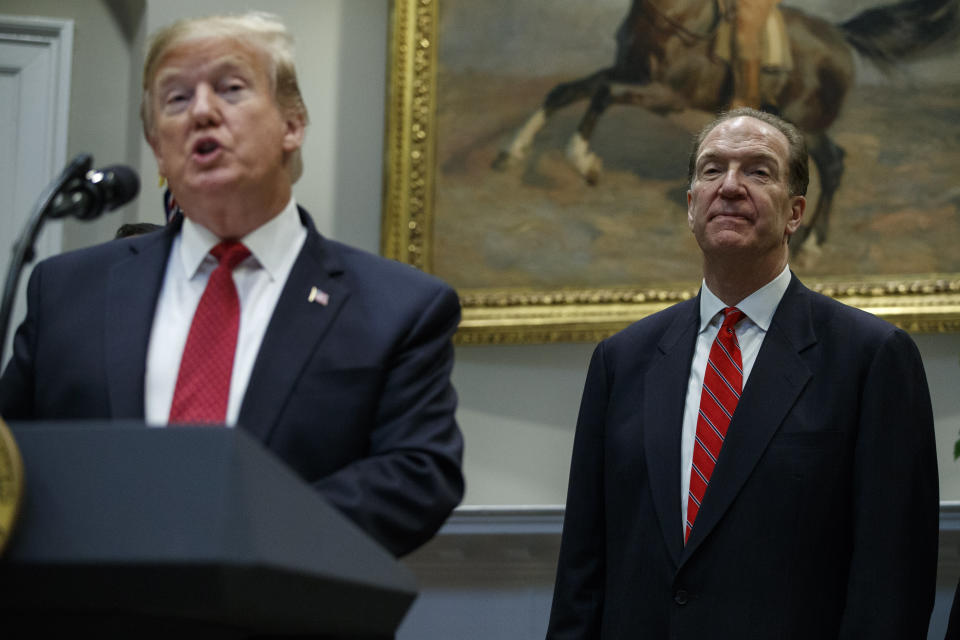

About a month after Kim announced his departure, Trump nominated Treasury Department official David Malpass to run the World Bank. In announcing the nomination in February, Trump said he hoped that Malpass would make sure that “U.S. taxpayers’ dollars are spent effectively and wisely” and that “financing is focused on the places and projects that truly need assistance.”

Once the chief economist at investment firm Bear Stearns, Malpass was best known for a 2007 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that infamously predicted that the unstable housing market — whose impending collapse would soon lead to a recession — posed no threat to the economy at large. An earnest and very public supporter of the Trump presidential campaign, Malpass never let his loyalty flag.

After his nomination was made public, some worried that Malpass would only weaken an institution that has struggled to fend off a criticism captured in a 2012 headline from the Financial Times: “The World Bank is flirting with irrelevance.”

“Our dream is a world free of poverty,” reads the bank’s motto, engraved in the airy atrium of its headquarters in downtown Washington. The World Bank seeks to achieve that mission by giving loans tendered on terms far more favorable than what the private marketplace has to offer, making for a curious mix of philanthropy and high finance.

The United States is the World Bank’s largest shareholder, and by longstanding agreement, the American president appoints its leader. Last year, Washington contributed about $1.1 billion to the bank, far more than any of its other 188 member nations. Trump, despite his antipathy to internationalism, can’t eviscerate the World Bank as if it were the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau or some other government agency hated by conservatives. That was why, even as Trump sought to remake the federal bureaucracy in the image of “America First,” the World Bank remained a redoubt of internationalism.

But with a Trump appointee now installed at the glass headquarters overlooking Pennsylvania Avenue, that could change. For many at the World Bank, a Trump takeover of a signature multilateral institution was exactly what those inside it wanted to avoid. But it was also facilitated by what was an already weakened institution after seven years of chaos under the previous World Bank president, according to nearly 20 current and former senior bank officials who spoke to Yahoo News for this article. Those officials describe those years as marked by self-aggrandizement and excess, confirming the worst Trumpian stereotypes about “globalists” while reinforcing long-standing criticisms of the World Bank.

When the World Bank was established in 1944 at the Bretton Woods Conference, international development was a new concept. There were still European colonies in Africa, while Europe’s own financial institutions were devastated by the soon-to-end war. That war’s aftermath would also sequester much of Eastern Europe behind the Iron Curtain, making institutions like the World Bank important weapons in the West’s Cold War arsenal.

But the institution has also suffered from ideological whiplash, not to mention a dose of scandal.

In the 1970s, the bank was run by Robert McNamara, who as defense secretary to John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson helped lead the nation into the Vietnam War. He “viewed the Bank presidency as a way to redeem himself after Vietnam,” wrote Patrick Allan Sharma, a historian of McNamara’s tenure at the World Bank, focusing explicitly on poverty reduction while expanding the bank’s “borrowing and lending portfolios, staff size, and research program.”

But as the bank grew, so did concerns about institutional excess, underscored by the contrast between well-paid bank employees and the poor countries they were supposed to be serving. In 1983, a Democratic lawmaker called the World Bank ''a fat-cat institution run for the benefit of the officers.” Whether fully fair or not, the image stuck.

Paul Wolfowitz — who as deputy defense secretary pushed George W. Bush into war with Iraq — made news at the World Bank for another reason altogether after becoming its president in 2005. Even as he vowed to eliminate corruption in the bank’s lending practices, Wolfowitz became ensnared in a scandal of his own, as it came to light that he had advocated for an improper pay raise for his partner Shaha Riza, an economist at the World Bank. Wolfowitz was forced to resign in 2007, after a contentious meeting with employees.

Today the World Bank does not enjoy the prominence it did in the second half of the 20th century, in large part because the kind of cross-border financing it pioneered has become commonplace. There is now a global finance system, one that has reached without trepidation into the developing world. Investment in emerging markets has risen steadily in recent years and now stands at more than $1 trillion annually. And there has been a smaller but also significant movement away from large institutions, toward smaller, nimble ones.

These forces conspired to turn the World Bank into a “vanishingly small institution,” says Scott Morris, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development.

President Barack Obama’s pick to lead the World Bank was supposed to change that. Obama nominated Kim in the spring of 2012 to be the bank’s first nonwhite president, as well as the first to come from the field of public health. The son of Korean immigrants, Kim rose to be the director of the AIDS/HIV program at the World Health Organization and, after that, a global health expert at Harvard Medical School. In 2009, he was named the president of Dartmouth College, making him the first Asian-American to lead an Ivy League institution.

Kim’s nomination was greeted with enthusiasm at a time when issues of income inequality and quality-of-life disparity were coming to the fore. “An inspired and groundbreaking move,” wrote editorial page editor Fred Hiatt of the Washington Post. He approvingly cited the fact that Kim would be “the first bank leader who has dedicated most of his professional life to working with and for the world’s poor.”

A month before Kim was nominated, the 1818 Society — the official World Bank alumni association — published a report that offered a grim assessment of the institution. “Predictions of Bank irrelevance are mounting,” the report noted in its opening paragraph. The report also noted that the bank was “under-performing,” that staff morale was bad and that its problems as a whole were so severe that the “institution runs the risk of being seen ... as seriously damaged and in decline.”

Kim only made things worse, according to several former high-ranking executives at the bank who frequently interacted with the new president early in his tenure. Upon coming to the bank, he had wanted the staff in the president’s office dismissed, because he believed they were loyal to previous heads, remembers one executive from that time. The dismissals were initially blocked, but Kim did eventually manage to fire several senior staffers, all women, none for clear reasons.

“It was like an execution squad,” says one person who witnessed the firings and the effect they had on staff morale.

Kim, through a World Bank spokesperson, declined to answer questions about his tenure.

For his critics, Kim seemed to embody many of the worst stereotypes about the bank. According to several former senior executives, Kim chafed at limits on his spending. He wanted to fly on charter jets and to stay at hotels that were priced far above the bank’s guidelines. “I have friends who have travel expenses that are higher than my salary,” he said, according to one person who worked with him closely at that time.

Kim also cited security concerns to use World Bank resources for what some staffers said appeared to be blatantly personal benefit. He deployed, for example, World Bank security personnel to chauffeur his children to and from school at prestigious Sidwell Friends, according to a former senior World Bank executive familiar with bank operations. That executive’s account was confirmed by several other high-ranking World Bank staffers.

“We do not publicly discuss issues related to security,” a World Bank spokesperson said.

Some of Kim’s requests struck career staffer as petty transgressions that were nevertheless indicative of his priorities. Kim asked for the World Bank to pay for tree removal at his Washington house, again citing security concerns (the request was denied). He used World Bank funds to purchase two tuxedos for the 2013 presidential inauguration. A World Bank official told Yahoo News that Kim, after being told that clothing purchases were not permitted by bank rules, reimbursed the bank for that expense.

Kim’s spending came in contrast to the priorities he espoused, such as cutting some $400 million from the bank’s annual budget that had risen to about $2 billion by 2012, while also reorganizing what even many of his critics saw a hidebound bureaucracy. The institution “really needed change by the time Jim arrived,” says one vice president from that time.

Under Kim, the bank also strove to engage China, which in 2014 had moved to create a World Bank of its own, called the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. With assets of only $50 billion, it would be a 10th of the World Bank’s size, but the geopolitical challenge was hard to miss. The Obama administration said it would have nothing to do with the new Asian bank, which found an eager courtier in Kim. “We would welcome any new player,” he said. Several months later — just as the presidential primaries were beginning in the United States — Kim went to Beijing, where he announced a $50 million joint anti-poverty fund and met with officials of the new infrastructure bank, praising them effusively.

At the same time, China continued to borrow from the World Bank at rates that seemed far too favorable for a full-scale superpower, according to Morris of the Center for Global Development. “Clearly they are getting a subsidy by taking advantage of bank lending,” Morris said of China,” he said. “There is a case for China to be borrowing, but they ought to pay more for it.”

Kim’s first term wasn’t scheduled to end until 2018, but as the 2016 presidential election approached, he lobbied for an early reappointment by using the threat of a potential Trump pick, according to people familiar with the matter. The campaign succeeded, and the board gave him a second term in the fall of 2016, presumably insulating the bank from the White House until 2022.

But on Jan. 8, 2019 — less than two years into his new term — Kim abruptly announced an end to his six-and-half-year tenure with a brief address to a surprised staff, which had learned of his departure from news reports the previous day. Kim’s new employer was Global Infrastructure Partners, or GIP, a private equity firm in New York with a portfolio of $40 billion. A spokesman for GIP declined to discuss Kim’s hiring.

GIP had recently bought an Indian firm that has done business with the World Bank, leading to questions about conflicts of interest. Asked at his departure address if he’d cleared his new employment with the World Bank board, Kim said that he had not. But he did say that, after a yearlong “cooling off” period, his new employer would become “the best partner the World Bank Group has ever had.”

A month later, Trump nominated Malpass, a choice greeted by skepticism from both the press and World Bank loyalists, who feared he would, like Trump appointees across the U.S. government, work to dismantle the very institution he was charged to run. “US makes a poor choice for World Bank chief,” ran the headline of an editorial in the influential Financial Times, which said Malpass was “deeply sceptical of multilateral institutions” and worried about the bank facing decline and even demise. (Malpass declined requests to be interviewed for this article.)

Malpass, who became the bank’s president earlier this month, is expected to take the bank in a direction more consistent with the Trump White House. Foremost in this category, for Malpass and Trump, is China, which has borrowed $60 billion from the World Bank for 416 projects. He has made clear that China will soon lose the favorable lending terms to which it became accustomed under his predecessors. At a recent event with reporters, he reiterated that China “will be a much smaller borrower” in the future while reiterating the fact that extreme poverty is concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa.

What else Malpass may do is not clear, but many World Bank insiders fear the worst. As one former senior official told Yahoo News in her assessment of Malpass, “I am hard pressed to think about any positives.”

Of course, the realities of governing, which have often blunted the more radical intentions of the Trump administration, will likely play out with Malpass at the World Bank. “It’s hard for me to imagine that we will get the most hardline version of Malpass,” says Morris of the Center for Global Development. Malpass has already made some conciliatory moves, such as announcing that no “restructuring” of the bank is forthcoming. In his remarks to the press upon assuming the presidency, Malpass mentioned women’s empowerment and climate change.

That has not engendered much enthusiasm from World Bank alumni. “A thoughtful approach to a greater strategic focus is welcome,” the former vice president added about Malpass, “but I don’t think we will get it with him.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Trump was ‘fighting for his political life,’ his former lawyer says

'It's already begun': Feedback loops will make climate change even worse, scientists say

Revealed: The U.S. military's 36 code-named operations in Africa

Video shows extensive fire damage inside Notre Dame Cathedral

Concerns mount over Jared Kushner's role in GOP money machine