'A huge advance': Dell Children's performs first fetal surgery on Austin mom expecting twins

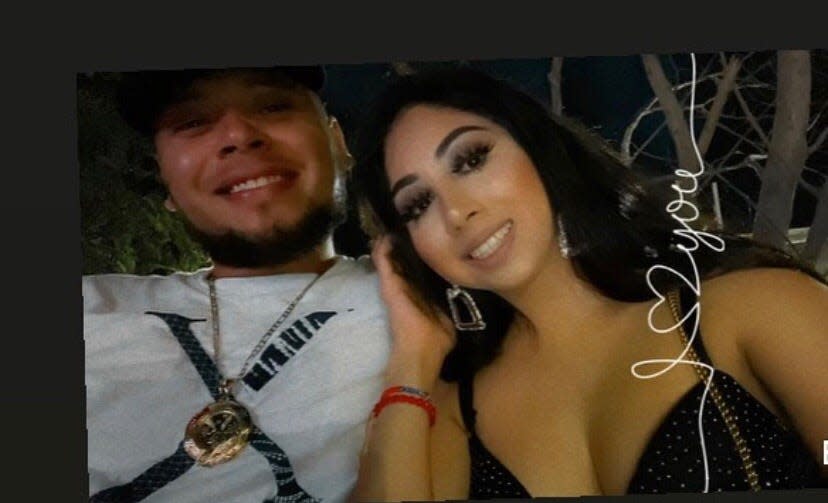

When the ultrasound at six weeks revealed that Jeanette Becerra was having twins, "we were really shocked," she said. None of her or her boyfriend's siblings had had twins.

"I was really scared," she said, but then she found some peace. "I know with God, I can do it. If God sends me two kids, I can do it."

That was in August.

Becerra didn't know there was more that she would need to handle. On Dec. 9, her babies underwent the first fetal surgery performed at Dell Children's Medical Center of Central Texas. Becerra was 22 weeks pregnant.

Twin-to-twin syndrome: Why her babies were at risk

In September and October, Becerra, 26, who lives in Cedar Park, was being sent from one specialist in Central Texas to another.

Her babies are identical twins who shared one placenta, and the same outer layer of the sack, while having separate inner layers. That happens when one embryo separates into two a few days later than is typical.

It put her babies at risk for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, when blood vessels from one baby are connected to the other baby. The blood from one baby then gets pumped to the other baby.

One baby effectively becomes the donor baby and has low amniotic fluid, less blood volume and a smaller bladder. The other baby, the recipient, has too much amniotic fluid, has an enlarged bladder and produces too much urine. While the donor baby is particularly at risk, both babies can die.

At one appointment, she was told it was almost 100% likely that her babies would develop twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and that Baby B was at risk of dying.

By November, Becerra was in the care of the new Comprehensive Fetal Care Center at Dell Children's. The center officially opened in May, though the co-director of the center, Dr. Kenneth Moise Jr., began working at Dell Children's and building the center in September 2020.

The center's goal is to offer more options to Central Texas babies diagnosed in utero with complications or disorders. Those options include fetal surgeries that previously would have required trips to Houston, Dallas or beyond.

"This is a huge advance for families in Central Texas," said Dr. Michael Bebbington, the center's other co-director, who arrived in July. "They don't have to leave home now."

A new center with experienced doctors

Moise and Bebbington have about 40 years of experience between them in caring for complicated babies in utero, including performing fetal surgeries. Moise joined Dell Children's from leading the Fetal Center at Children's Memorial Hermann Hospital in Houston. Bebbington had been the director at the fetal care center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and St. Louis Children's Hospital.

As with other recent areas of growth for Dell Children's, including cardiac and neurological care, the hospital is recruiting experienced physicians to start new programs here. Within the past two years, milestones have included the hospital's first cardiac ventricular assist device and first heart transplant.

Building a cardiac program: In first year of heart transplants, Dell Children's finds niche in cases other hospitals pass on

On the fetal care side, Dell Children's opened a labor and delivery unit inside the hospital in July to be able to deliver babies being cared for by the Comprehensive Fetal Care Center. The deliveries so far have been healthy patients with high-risk babies.

Next month, the Maternal Care Clinic will open. This will allow patients being seen by the fetal center to transfer their obstetric care to the Maternal Care Clinic at Dell Children's. Dell Children's is building toward being able to deliver mothers who are carrying complex babies and who have their own maternal pregnancy complications.

Dell Children's expects to do 250 deliveries a year.

New program begins: First baby born at Austin's Dell Children's hospital as labor and delivery unit opens

Next month, the Comprehensive Fetal Care Center expects to expand its fetal surgery to in utero surgeries for spina bifida. In that procedure, Bebbington or Moise and a neurosurgeon will open up the mother's abdomen, access the baby's back, repair the hole in the baby's spine and close everything back up.

"That is a whole other level of intensity," Bebbington said. It will require about three dozen people in the operating room for a three-hour surgery.

Doing that surgery in utero instead of waiting can allow the baby to be able to walk once it is a toddler instead of needing to use a wheelchair.

Bebbington said there will be nothing this center won't be able to do that other fetal care centers around the country are doing. The one exception, because of Texas laws, is the ability to offer a mother of a baby who will not be viable at birth the option not to carry the baby to term.

Starting a program: Even before official opening, Dell Children's fetal care center coordinating families' care

People are finding the Comprehensive Fetal Care Center. Bebbington and Moise are treating pregnant people from across Texas and around the country. They also get a lot of referrals from military families because of Austin's proximity to Fort Hood.

"Dell Children's has put in an incredible amount of resources," Bebbington said.

The new center: Dell Children's hospital opens new Specialty Pavilion with fetal care center, more family services

In the fetal center's care

Bebbington had been monitoring Becerra every week for weeks. Babies like hers, who share one placenta and one outer sack, have about a 15% chance of developing twin-to-twin syndrome, he said.

"We have to anticipate who is going to get into trouble," he said. Once they see the signs that it is happening, they usually try to operate within 24 hours. The earliest this happens is 15 weeks gestation. The latest is 26 weeks, but most cases of it happen earlier rather than later, Bebbington said.

Bebbington was looking for the telltale signs of the syndrome and that it had reached a stage that was putting the babies at risk. That is when the recipient baby is taking up most of the space and the donor baby is been crowded out and pushed up against the placenta. The difference in their amniotic fluid amounts is drastic. The recipient baby has 8 centimeters of amniotic fluid and the donor baby has only 2.

The syndrome also can happen in triplets and quadruplets or larger numbers of multiples when there is an identical twin set that shares the same placenta and outer sack.

When twin-to-twin transfusion happens, it carries an 85% mortality rate if left untreated, Bebbington said. The donor baby dies because it's not getting enough blood volume. The recipient twin can go into heart failure from having to pump the extra blood it receives. The death of one twin puts the other twin at a 40% risk of death, a 20% risk for stroke, Bebbington said.

For Becerra, the situation became critical Dec. 8. Doctors saw that dangerous shift in the amniotic fluid. By Dec. 9, Becerra was being wheeled into the operating room and put on conscious sedation.

"I didn't know how you could do surgery on a pregnant woman," Becerra said. If she had to rate her fear from 1 to 10, she said, she was a 10. "I did almost have like a panic attack. I cried because it was my babies' lives. I was really scared."

Before they start doing any new procedure at the hospital, staff members do several simulations to work out problems before a real patient is involved. On Dec. 1, Dell Children's knew it was ready for the real thing, but there had to be a first one, and Becerra would be it.

During the surgery, she could see all the doctors and nurses, but she couldn't feel anything. She would close her eyes, fall asleep and then wake up again.

Fixing the twins

Becerra was given medication to prevent preterm labor and infection. The doctors do an ultrasound to map out the blood vessels that are overlapping between the twins. They also figure out where they are going to enter the abdomen and uterine wall to reach the placenta. Then they repeat the ultrasound to make sure nothing has changed.

They put a tube that looks like a plastic straw through the abdomen and into the uterine wall. Then they can thread a scope inside the tube to see the blood vessels.

They start from one end of the placenta and work to the other. Using a tiny laser, they cauterize the blood vessels that are connected. Then they do the "Solomon technique," which is to use the laser to draw a line on the placenta between the two babies to try to prevent missing any tiny blood vessels that are connected that they can't see. The hope is that new connected blood vessels will not cross the line.

"No two placentas are the same," Moise said. Becerra's babies had 17 shared blood vessels that needed to be cauterized. That is considered a high number, but the most Bebbington has ever seen was 28.

The whole procedure takes about an hour. There are risks, including bleeding and infection. About 15% to 18% of the time both babies do not survive. Sometimes one baby won't make it but the other will. About 74% of the time both babies survive, which is better than the 85% death rate if doctors did nothing, Bebbington noted.

After the surgery, the babies begin to normalize with the recipient baby beginning to pump its own blood. The recipient baby's bladder size reduces, including how much it is urinating, and the baby has less amniotic fluid around it. The donor baby then pumps only its own blood and is able to urinate again if it stopped. The baby's bladder size increases, and the baby begins to take up its own space and have a normal amount of amniotic fluid.

Becerra's babies will be watched throughout the rest of the pregnancy, looking for signs that twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome is happening again. That's rare, but doctors can go back in with the laser to disconnect shared blood vessels.

Waiting for delivery: 'These are my first babies'

Becerra already has noticed a change. She was really swollen before with the excess amniotic fluid of Baby A (the recipient). She also had a lot of pain around her ribs because Baby B (the donor) was trying to create any kind of room he could and was pressed up against her ribs.

"I'm feeling much better," she said.

Every week she comes into the center to look at the babies by ultrasound. It's a relief when she hears their heartbeats. Already, they can tell that Baby B (the donor baby) is urinating again, and they can see his bladder and that he's now getting enough blood and nutrients.

There can be some lasting effects of the twin-to-twin transfusion, such as an impact on neurodevelopment, but not always.

"I know I'm in the right hands," Becerra said, "and he's doing everything he can. We're just waiting for delivery."

The babies are due April 15, but they will be delivered around 33 weeks to minimize late-term pregnancy complications. Until then Becerra will be on bed rest to make sure she doesn't go into labor early.

"I'm excited," Becerra said. "These are my first babies. I don't want to lose them."

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Dell Children's performs fetal surgery to fix twin-to-twin transfusion