The Humana Tower was an architectural marvel, its place in Louisville history must be remembered

The 27-story Humana Tower, with its pink granite, marble, bronze and steel design rising above cast-iron Main Street for almost 40 years, became a Louisville landmark and a national architectural icon.

It’s design came after a contest among five of the country’s leading architects. Their role was to meld Louisville’s past—its Ohio River waterfront and steel bridges—into a future mix of art, architecture and poetry.

The tower cost more than $60 million in early 1980s money. It inspired praise and was ridiculed as a giant pink cash register. What mattered most was it inspired conversation, tourists, Main Street development and a hopeful push for other iconic buildings to follow. The Humana Tower’s 24th floor balcony offers a literal and figurative view of Louisville’s possibilities.

Then came the news that the home-grown, Fortune 500 Humana will abandon the tower to consolidate its employees at Humana Waterside and Clocktower buildings renovated at what had been the old Belknap Company nearer the river.

Company officials explained the move was needed because of the roughly 10,000 Humana employees in the area, only about 2,500 were working in the downtown offices daily. The consolidation will allow all those employees to work at Waterside or Clocktower.

Humana Tower is an integral part of Louisville history

No decision has been made about what will happen with the Humana Tower, but it’s design, construction and place in Louisville history need to be remembered. It’s a good story: Think local. Dream big. The tower’s prime creators and dreamers—and also very pragmatic men—were Humana founders David Jones and Wendell Cherry. They became best friends, with each bringing specific talents and backgrounds, if not geography, to the job.

Jones grew up one of six children in a small, blue-collar West Louisville house on Garland Avenue, four boys in one bedroom. He lived at home while attending the University of Louisville on a Navy ROTC scholarship, serving three active and cherished years in the Navy afterward. He went on to Yale law school in New Haven, Connecticut while working three part-time jobs. He and his wife, Betty Lee Ashbury Jones, his U of L sweetheart, lived at Yale in half of a steel-domed Quonset hut with their first two children. They came back to Louisville in an old station wagon, having to post-date a $15 check to buy gas in Covington.

Wendell Cherry was the son of a grocery wholesaler from Horse Cave Kentucky. He led his Caverna High School basketball team to the state high school semi-finals, earned a law degree from the University of Kentucky, became an international art collector and was nicknamed “Horse Cave Harry” by his friends. In 1981, only 20 years after he and Jones each borrowed $1,000 to build a nursing home that would evolve into Humana with $90 billion in sales, Cherry purchased a Picasso painting for $5.8 million. Eight years later he sold it for $47.9 million.

The Humana Tower rising above 500 W. Main Street came along with that success. Jones, who died in 2019, would explain that he and Cherry, who died in 1991, wanted a unique, environmentally-friendly building reaching well beyond anything the city skyline had to offer. It’s goal was to promote Humana nationally, but also to set local architectural standards to be exceeded by newer buildings.

Humana building began with a design competition

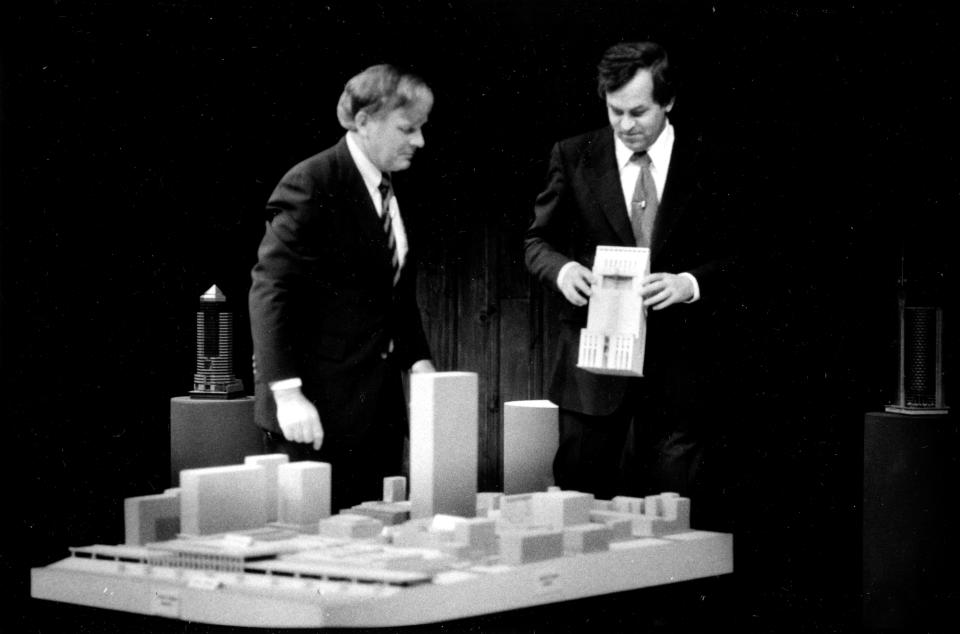

It began in 1981 when the two men held a design competition that originally included about 35 names. That was reduced to five of the world’s most eminent architects, Norman Foster, Ulrich Franzen, Helmut Jahn, Cesar Pelli and Michael Graves. Each was paid $7,500 to come up with a design, a technique not used since a 1920s design contest to build the Tribune Building in Chicago.

Jones and Cherry further wrote about their hopes a preface to a book about the building:

“Our desire was for the participants to focus on its location: the 19th century architecture, the mix of other buildings in the immediate area, the imposing geographic prominence in the city, and most important, the Ohio River – where the city’s life began. We further desired that the building enhance the overall visual impression of the Louisville skyline.”

Louisville architect and Bravura Corporation founder Jim Walters worked with David Jones on many Louisville projects, including the 4,000-acre Parklands of Floyds Fork. He, along with architect Bob Harris, were involved in the initial phases and interior of the Humana Tower.

At one point all the Humana Tower candidates were brought to Louisville together. They walked Main Street, with its cast-iron-fronted buildings and the city riverfront, with Louisville historian Tom Owens to get a feel for city.

Jones and Cherry made the final selection a little bit of a game. Each had a favorite but didn’t tell the other until the end. Both picked Michael Graves, the least known of the five men, an architect with a post-modern vision to get away from the tall, slick, glassy buildings then so prominent in most American cities..

Grave’s 650,000-square-foot design with built-in fountains came with its now familiar eight-story base of pink granite, and an open arcade of red granite. Above it, but set back, was the main slab of the tower sheathed in pink granite and punctuated by small windows. The windows gave way to a large expanse of glass leading to a huge metal truss, then a large balcony/observation deck. The building’s fountains to bring the Ohio River into play, the trusses a reminder of its bridges. Its marbled lobby welcoming, it’s many offices nicely-lit, it’s amenities including a cafeteria, sitting spaces and gym facilities handy and useful.

Walters said one immediate problem with the building construction was the initial bid from an American source for the almost 33,000 pieces of five-different colors of granite required came in at about three times the projection.

By sheer luck Walters was at an architectural conference in New York when he heard of a granite vendor in Carrara, Italy who might be able to help. The next Monday Walters was off to Italy. He visited three quarry companies talking with the vendor, who lined up the granite from five different countries: Finland (pink), Brazil (green), Angola (black), India (red) and Sardinia (gray). Each source shipped the granite to Carrara where it was cut, metal fasteners were attached and shipped and trucked to Louisville to be placed on the tower.

Construction began in October 1982 and was completed in May 1985. Walters said the construction workers, mindful of the scope, scale and source of materials, took special pride in the building. Some acrobatic moments were required. The installation work was often very complex, one worker saying they were using modern tools and equipment but methods more reminded of his grandfather.

Despite critics, Humana Tower was an architectural marvel and an inviting place for all

The Humana Tower was not without its critics, among them calling it a cash register, a big pink razor, a hindrance to pedestrians and just plain awkward. There were complaints that no local architectural firms had been invited to compete.

A future Louisville: Ditch the business-focused downtown model for the mixed use urban neighborhood

On the other side, some Humana employees wrote of the personal joy of working in such a building, of finding quiet sunny places to gather and talk. Others complained of parking in the basement where street people might hang out.

For all that, Time Magazine labeled it one of the top ten buildings constructed in the 1980s. It received a National Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects in 1987.

Paul Goldberger of the New York Times wrote in 1985, “Humana is a striking example of a large, prosperous corporation seeking to build a headquarters structure that would stand as a statement against conventional, modernist corporate architecture.

“Humana is a warm and inviting building. Perhaps the first skyscraper of our time to be both serious and visually alive. Far too long architecture has taken itself quite seriously and has been a deadly bore, and architecture that has been lively has tended to be frivolous.

But Humana is neither boring nor silly—it is at once a building of great dignity and a building of great energy and passion.”

The future of Humana tower is unknown

The Human Tower’s future is, well, up in the air. Suggestions in a recent on-line survey included mixed income apartments, a broad-based-library, an arts and tech high school, condos, a hotel and, this being Kentucky, some sort of basketball facility or a car wash.

Humana officials said the building will be vacated over the next 18 to 24 months. The company has not decided if it will sell the building. It has engaged in conversations with Mayor Craig Greenberg looking for uses that will help the city. Greenberg said the city will be pushing for a strong vibrant future for the building. Creating more downtown problems, Fifth Third Bank has announced it will leave its offices in the Fifth Third Tower that bears its name at 401 S. Fourth Street to move to NuLu. No other information was released.

Gerth: Humana Tower's closure is another death knell for downtown Louisville

One possible problem with the Humana move is a lawsuit the company filed last March against Michael Graves firm as well others involved in its construction, citing structural defects in some welds. Humana said the building is safe to occupy, but has garnered significant costs to fix these defects, which could take four or five years. The defects were only discovered in a 2019 building renovation.

Somewhat ironically, the Waterside building which will take in many of the Humana Tower employees, was once part of Belknap Hardware. It was an historic, but financially-strapped, hardware giant David Jones purchased in 1984 for $35 million trying to save it for the city from an outside buyer. Belknap went bankrupt in 1986. Jones put up another $25 million of his own money—which he didn’t have to do—to pay all the Belknap creditors and save the pensions of the employees.

Bob Hill was a Louisville Times and Courier Journal feature writer and columnist for 33 years.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: The rich history beauty of the Humana Tower must be remembered