Humans Broke Up with Neanderthals Much Longer Ago Than We Thought

The exact point that humans and Neanderthals diverged from each other has long been a matter of intense debate among scientists. But thanks to an extensive dental analysis recently published in Science Advances, the split-off now looks like it happened at least 800,000 years ago.

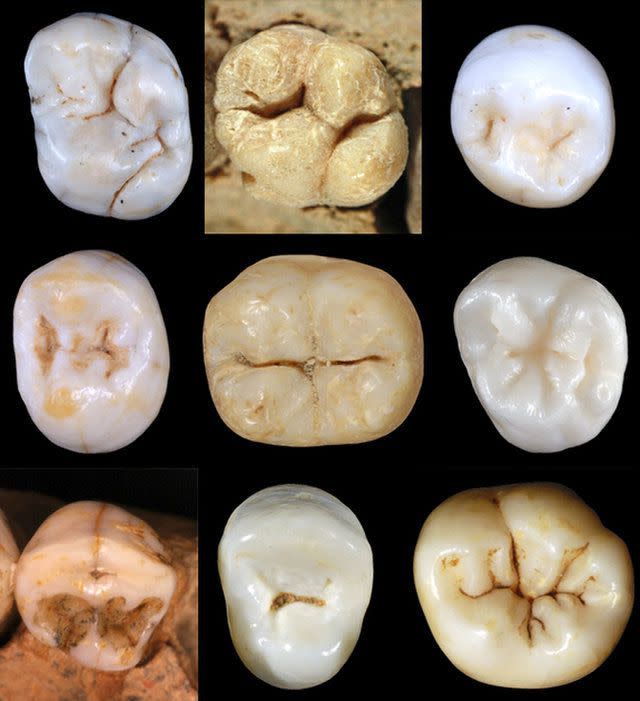

That's according to Aida Gómez-Robles, a paleoanthropologist at University College London, who examined nearly 1,000 teeth from humans and related species, like Neanderthals, to reach the conclusion. Specifically, Gómez-Robles looked at 931 teeth that belonged to a minimum of 122 individuals from eight groups; 164 of the teeth originated in the mouths of the early Neanderthals from the Sima de los Huesos ("Pit of the Bones") site in Spain.

Through her research, Gómez-Robles was able to track the evolutionary rates for dental shape change throughout history. From there, she estimated the divergence time between the final common ancestral link between humans and Neanderthals.

Many scientists think that link takes the form of Homo heidelbergensis, the first human ancestor to live in colder climates. But Gómez-Robles disagrees.

"H. heidelbergensis cannot occupy that evolutionary position because it postdates the divergence between Neanderthals and modern humans," Gómez-Robles tells the website Live Science in an email. "That means that we need to look at older species when looking for this common ancestral species."

Gómez-Robles says the study "has profound implications for the way we interpret the fossil record and the evolutionary relationships between species."

While outside scientists praise Gómez-Robles' work in setting the European timeline straight, they're cautious about global implications. The main challenge: If the two species broke apart at least 800,000 years ago, it doesn't quite gel with the fact that they were able to interbreed a mere 60,000 years ago.

"In other words, almost 1 million years of evolution was not enough to establish barriers (genetic, endocrinological, behavioral, etc.) to separate definitively these two species?" asks Fernando Ramirez Rozzi in an interview with LiveScience. Rozzi, the director of research specializing in human evolution at France's National Center for Scientific Research in Toulouse, was not involved in the study.

While parts of Europe might have "their own particularities," says Bruno Maureille, director of research at the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), in Paris, who was not involved in the study, the question remains: "Can we simply try to draw such global scenarios? [I'm] not so sure."

There are a lot of unknowns when it comes to the Neanderthals. For example, another relative of the ancient species, the Denisovans, were thought to have only lived in a single cave for all of their existence. But now, thanks to the recent discovery of a jawbone, we now know that they lived in Tibet and share DNA with the modern people who still live there.

Source: LiveScience

('You Might Also Like',)