Hundreds in NC lose homes, equity after HOAs foreclose. Who protects homeowners?

When Eric Peper fell behind on paying his quarterly dues to his homeowner association, he had no idea the HOA could foreclose on him.

“I found out the hard way,” he said.

In 2019, after buying a three-bedroom house in southwest Charlotte for $210,000, Peper began replacing floors, putting in granite countertops, and, with a 3% mortgage interest rate, building equity.

But his job fixing machine tools slowed during the pandemic, and by July 2021, he was $435 behind on his dues to the Steelecroft Place Homeowners Association. He made sure he paid his mortgage on time, he said, but figured he’d pay the HOA when he got his next tax refund.

Instead, his HOA foreclosed on him. In 2022, a company named DEV Properties, LLC, bought the house out of foreclosure for $3,700. Peper lost his house, along with his equity, and had to move into a small, rented bedroom.

Hopes Foreclosed

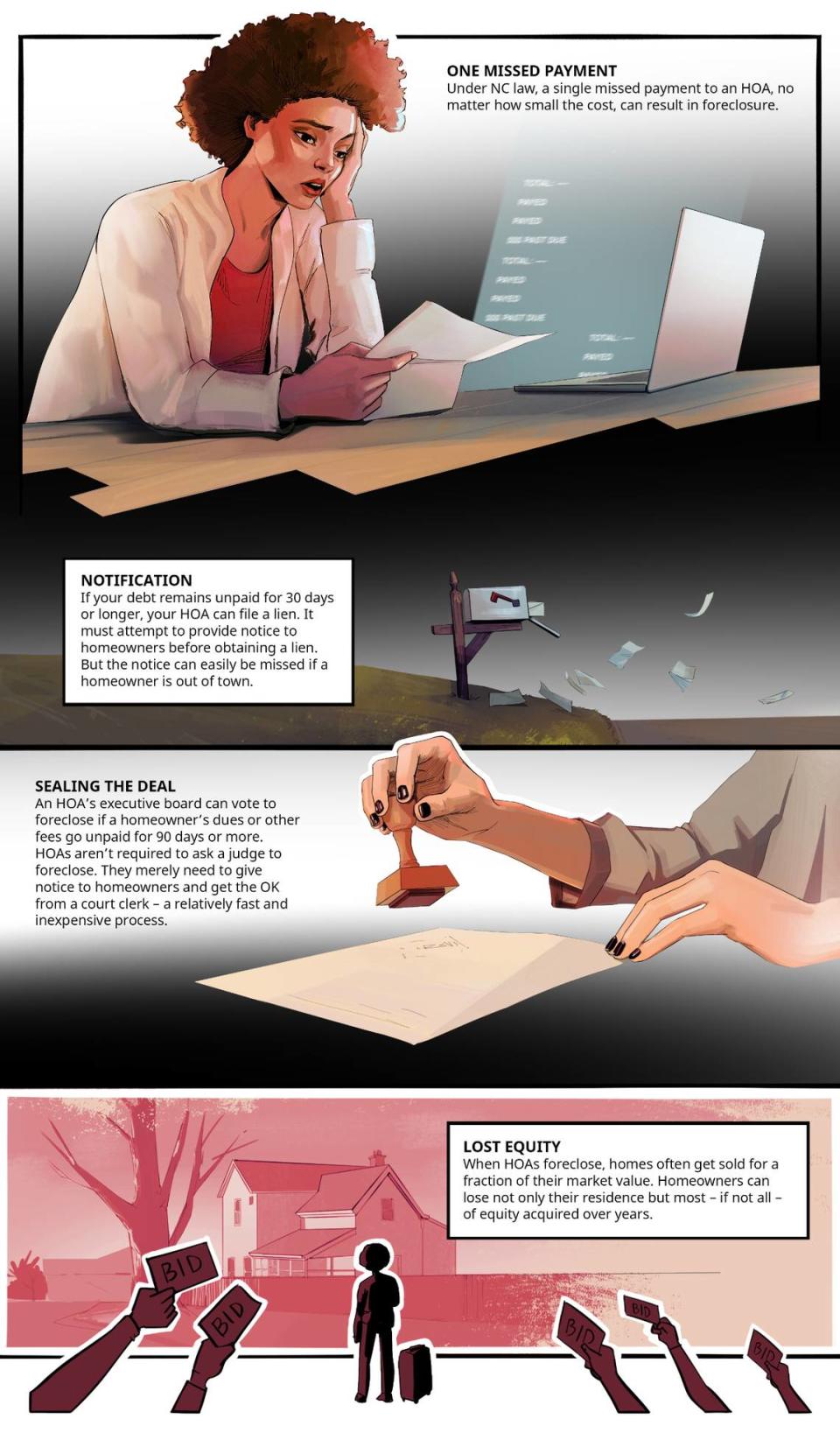

NC rules make it easy for HOAs to foreclose on homeowners. State law allows them to force the sale of homes for any amount of unpaid dues, no matter how small. Our investigation shows how often it's happening — and how it can be devastating to homeowners.

Hundreds in NC lose homes, equity after HOAs foreclose. Who protects homeowners?

Deceit, rigged bids and extortion: How HOA foreclosures can open the door to predators

‘Once. Twice. Sold for $4,400.’ How HOA foreclosure auctions cost owners their homes

Can an HOA sell your home? What NC law says, and how to challenge foreclosures

“I’ll never live in a neighborhood with an HOA again,” said Peper, now 55. “The HOA has all the power in North Carolina.”

Peper is among hundreds of North Carolina homeowners who lost their homes to HOA foreclosures since 2018.

North Carolina rules make it easy for HOAs to foreclose on homeowners. State law allows them to force the sale of homes for any amount of unpaid dues, no matter how small. They simply need to obtain approval from a court clerk — a relatively quick and inexpensive process.

The Charlotte Observer and The News & Observer pored over hundreds of court documents, analyzed state data and interviewed homeowners, experts and attorneys to conduct a first-of-its-kind investigation of HOA foreclosures in North Carolina. We found:

▪ HOAs in the state have filed to foreclose in more than 5,500 cases since 2018, against owners of houses, condominiums and time shares. In more than 600 cases, owners lost their property or time-share stakes. Forty-five percent of the state’s foreclosure filings happened in a single county: Mecklenburg.

▪ Small debts can result in big risks for homeowners. Our analysis of more than 100 HOA foreclosure cases showed that about half of the homeowners had debts of less than $2,000. Some owed less than $500 in dues.

▪ HOA foreclosures have opened doors to financial predators. One North Carolina firm engaged in bid-rigging to limit competition and help its investors buy foreclosed homes at lower prices, a federal jury found. It also encouraged investors to use the threat of taking homes as a way to shake down owners for tens of thousands of dollars.

▪ Those who lose homes to HOA foreclosures typically are stripped of most — if not all — of their equity. In a review of more than 250 cases from 2018 to 2022, the newspapers found that 62% of foreclosed homes sold for less than $10,000 — a fraction of their market value. That leaves little or no money for the homeowners.

Johnnie Larrie, Director of the Economic Justice Initiative for Legal Aid of North Carolina, said her office regularly hears from homeowners who’ve faced foreclosure over small debts. Most, she said, were current on their mortgage payments — or had paid off their mortgages — but fell behind on HOA dues.

“You can owe so little,” Larrie said. “And you can lose so much.”

State court records show a decline in foreclosure sales since the pandemic struck. The national group that advocates for HOAs — the Community Association Institute — recommended a pandemic-related moratorium on foreclosures from March 2020 until at least July 31, 2021. While many HOAs heeded that guidance, more than 550 HOAs in North Carolina filed foreclosure actions during that time period, the newspapers found.

Larrie and other homeowner advocates say they expect to see an uptick in foreclosures, now that federal housing aid that was available during the pandemic is nearly exhausted.

Behind on HOA dues? You could lose your home

HOAs: We need a way to pay our bills

More than a quarter of North Carolina residents live in HOA communities, and many of them are happy with their associations. In a 2022 survey by the HOA industry’s research arm, the Foundation for Community Association Research, 61% of homeowners in HOA communities here rated their experiences as good or very good.

Foreclosure filings represent just a tiny fraction of the more than 1 million homes in HOA communities.

North Carolina, the nation’s ninth-most populous state, has nearly 15,000 HOAs — more than all but four other states. The vast majority of those associations never move to foreclose on homeowners, state courts data shows.

Attorneys representing HOAs say the organizations need the power to foreclose so they can continue to pay for essential community services such as water and sewer without raising dues for others.

State law ensures that homeowners who fall behind on their dues are given plenty of notice — and many opportunities to pay their debts so they can avoid losing their homes, they say.

Cynthia Jones, president of the North Carolina chapter of the Community Associations Institute, said most HOA board members are hard-working volunteers who bear no ill will toward their neighbors.

“They don’t want to take anyone’s home,” she said. “They just need the money to pay their bills.”

But attorneys who’ve battled foreclosure actions say state law is tilted against homeowners. If owners feel an HOA’s actions are unwarranted, there is no state or federal agency they can turn to. One of the few things people can do is file a lawsuit — an expensive proposition that is beyond the reach of many.

HOAs, meanwhile, can recover their legal fees on foreclosure cases by billing the homeowners who owe them money.

And while federal rules require mortgage lenders to work with homeowners to avoid foreclosure, HOAs face no such requirement, notes Kara Fisher Moskowitz, who heads the Charlotte Center for Legal Advocacy’s consumer protection program.

“Homeowners are often taken by surprise, Moskowitz said. “And there’s not a lot they can do to curb abusive HOAs, other than hire an attorney.”

How foreclosures work

In North Carolina, if you’re 30 days behind on paying your HOA dues, the association can file a lien against your property. And if you fall 90 days behind, an HOA can move to foreclose — over any debt, no matter how small.

In more than a third of U.S. states, representatives for HOAs must appear before a judge to get the authority to foreclose on a home. But not in North Carolina. Here, attorneys who represent HOAs usually get the OK during a brief hearing with a clerk in a county courthouse.

Clerks check whether the homeowner failed to pay dues, whether the HOA filed a lien, whether the HOA board authorized foreclosure and whether the association has evidence that it made required efforts to notify homeowners about its plans to foreclose. If the answer to those questions is yes, approval is virtually assured.

It’s not a forum where homeowners are given a chance to argue against foreclosures for other reasons, even if they have evidence the HOA failed to properly handle finances or maintain the community, lawyers familiar with the process say.

When new buyers purchase HOA foreclosure homes, the associations and their attorneys are the first to collect. If a house is bought out of foreclosure for more than the HOA and its attorney are owed, the “surplus proceeds” must legally go to the homeowner. Usually, though, the property sells for such a low amount that the original homeowner collects little or nothing.

Any existing liens by mortgage lenders remain on the house after the foreclosure sale. But the foreclosure buyers can often turn a large profit because they typically buy the homes for less than $10,000 and sell them for much more than is needed to pay off the mortgage. The original homeowner sees none of the profit from the second sale.

Even if a case does not move all the way to foreclosure, the process often proves costly to homeowners. State law gives HOAs the right to bill homeowners for “reasonable” attorney fees — up to $1,200 in uncontested cases — as well as other costs associated with the collection of a debt.

Devastating losses

In interviews with six homeowners who lost their houses to HOA foreclosures, an Observer reporter heard a common refrain: The experience financially devastated them.

Todd Harris, a 59-year-old maintenance mechanic, doesn’t like to drive near his old neighborhood. It reminds him of all he has lost.

Almost 20 years ago, Harris borrowed from his 401(k) to make a down payment on a new two-story house that had everything he wanted: four bedrooms, 3,200 square feet of space and a two-car garage. It was in a tranquil, ethnically mixed neighborhood with two ponds, just 15 minutes northeast of downtown Raleigh. He’d planned to retire there.

But Harris fell behind on paying his dues to the Pine Hall Plantation HOA several years ago. In a letter sent to Harris in April 2019, the HOA’s management company demanded payment of $521 for past dues.

He’d planned to catch up on the payments, but the bills the HOA sent soon included large additional sums for attorney fees, he said. He didn’t have the money to pay it all off, he said, so he asked the HOA’s attorney if he could negotiate a repayment plan. He was told he couldn’t, he said. They wanted all of the money.

On June 9, 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, the directors of Harris’ HOA voted to foreclose on him.

In August of 2021, a sheriff’s deputy posted a notice of the foreclosure hearing at Harris’ home, records indicate. Harris said the foreclosure notices didn’t quickly come to his attention because he’d been spending most of his time at his girlfriend’s house at the time. No one tried to call or email him, he said.

“I should never have let it get to that extent,” he said. “But I also think there should have been a better effort by the HOA to let me know how serious the situation was.”

When Harris finally saw the notices, he called the HOA attorney. “But by that time, they said it was too late,” Harris recalled.

In 2022, a company called YL Properties bought the house out of foreclosure for $115,500. Harris was told he had two weeks to pack his things and leave.

Unlike many who lose their homes to HOA foreclosures, Harris did get a sizable check from the sale — a little over $100,000. But he lost much more than he gained.

He lost more than $200,000 of the equity he’d built, he said. He lost the home where he’d hoped to retire. He moved into a rented, 10-by-10-foot bedroom in Morrisville, where he sleeps on an air mattress.

His old house, meanwhile, was sold to new owners this April for $540,000.

“To take everything I worked for the last 20 years …” said Harris, now 59, leaving his sentence unfinished. “It’s been rough.”

Hope Derby Carmichael, a Raleigh lawyer who represented the HOA, said fair debt collection laws prohibit her from commenting on such cases.

HOAs don’t always try to take homes to settle debts. They must first file liens to pressure homeowners to pay up. If that doesn’t happen, liens allow HOAs to collect money owed when homes are sold. But a quarter of the roughly 5,600 HOAs that filed liens from 2018 to 2022 went on to file for foreclosure, the newspapers’ analysis found.

Harris said he understands the purpose of HOAs. They keep neighborhoods attractive. And he believes HOAs should be given tools to collect on what they are owed.

“But there should be more requirements in place before they can foreclose on your home,” he said.

Small debts, big losses

When North Carolina HOAs move to foreclose, they often do so over small debts, the newspapers’ investigation found. And overdue bills frequently mushroom because HOAs tack on attorney fees, late fees and other costs.

Keith Williams’ house troubles began about five years ago, when he said he forgot to pay his annual HOA bill.

In March of 2018, his HOA, Chastain of Raleigh Community Association, sent the Army veteran a notice saying he owed $192. Two months later, the HOA put a $526 lien on his house for late dues and attorney fees. The HOA board voted to pursue foreclosure in June, and by August his debt had grown to $1,590, according to a letter from the HOA’s attorney.

It kept climbing.

One morning in mid-2019, Williams responded to a knock on his front door and was met by a sheriff’s deputy and a locksmith. The deputy told him that the HOA had foreclosed on him and that he had five minutes to pack up his things and leave, he recalled.

“That is a pure disgrace,” Williams said. “You’re telling me you’re going to kick a veteran out of his house because he didn’t pay $300?”

Williams had bought the three-bedroom house in southeast Raleigh about 10 years earlier and estimated that he had about $30,000 in equity in it. But his HOA got possession of the house by bidding just $2,922 on it in the foreclosure sale.

With nowhere to go, Williams slept in his van in a Walmart parking lot for the next week. The HOA told him he could save his house if he quickly came up with about $4,000, Williams said. With the help of friends, family and viewers of a TV news story about his ordeal, he was able to raise the money and get his house back.

Since 2018, Chastain of Raleigh has filed at least 26 foreclosure actions, state courts records show. And the association kept pursuing foreclosures in 2020, after many HOAs put a pause on foreclosure actions because of the pandemic.

Kristina Bailey, a community manager for the HOA’s management company, declined to discuss Williams’ case, referring a reporter to Carmichael, the association’s lawyer. Carmichael also declined to talk about the matter.

Some lawmakers see a need to rein in HOAs.

An early version of North Carolina House Bill 542, introduced earlier this year, would have prevented HOAs from putting liens on homes and foreclosing for debts of less than $2,500, or one year of assessments. But the North Carolina HOA association opposed that measure, according to its legislative action committee. And the provision was removed from the bill.

A diluted version of the bill did not pass in this year’s legislative session, but lawmakers may take it up again next year.

Jones, the lawyer who heads the North Carolina advocacy group for HOAs, said that limiting foreclosures could put a financial strain on associations.

“If you have an association with a large number of people who are $2,500 behind, they are severely hurting,” she said.

Rep. Ya Liu, a Wake County Democrat who introduced House Bill 542, said she doesn’t buy the argument that such limits would cripple HOAs. A number of other states, including Georgia, have set dollar limits on HOA foreclosures, she noted.

“It’s been very hard to push any HOA legislation through,” Liu said. “Because HOAs have pretty strong arms and they can reach the leadership in the House and Senate.”

Did homeowners get adequate notice?

Some homeowners say they had no idea they were in danger of losing their homes until it was too late.

Gina Ackah owned a three-bedroom house in Raleigh, and began renting it out when she moved abroad for a new job, court records show.

She was current on her mortgage and had built up significant equity in the home. But she fell slightly behind on her HOA dues and in 2015, the HOA foreclosed on her to collect past dues of about $200, according to Ryan Adams, an attorney who represented her. The high bidder in the foreclosure auction bought the home for just $2,709.

Ackah was working for a petroleum company in Africa at the time and never received word of the foreclosure proceedings because the notices were forwarded to her uncle’s home in South Carolina — and not sent to the email address that the HOA had for Ackah, court records show.

Ackah took the case to court and won a hollow victory. Both a trial court and the state Court of Appeals agreed with her assertion that she did not receive notice of the HOA’s plan to foreclose.

But the appeals court declined to return the house to Ackah, leaving her with no remedy but to seek restitution from the HOA. She chose not to pursue that restitution because of the legal costs involved, Adams said.

“When you have contact information for a resident, it just seems like they should have to do everything reasonably in their power before starting a foreclosure and taking a home,” Adams said.

Lucian Cooke also contends his HOA provided insufficient notice before foreclosing.

In early 2020, he bought his first home — a three bedroom townhouse located in a quiet neighborhood in northeast Charlotte. The home quickly grew in value, and he was depending on the equity to help provide a comfortable retirement.

He said he had been paying dues to one HOA, but forgot that he also was responsible for paying dues to a second one. (Some homeowners have to pay dues for two HOAs — an umbrella association that oversees a large community and a sub-association governing a section of the community.)

Cooke took a job in Chicago for seven months so he said he didn’t see any of the mail his HOA had sent him during that time period.

“I got no emails, no phone calls, no certified mail,” he said.

One day, he recalled, his girlfriend was at his house when someone came to the door with disturbing news: “I own the house now. I’ve got the deed.”

The Davis Lake Community Association had foreclosed on the home to collect on a bill of $2,349. And in May 2022, a Charlotte LLC called DEV Properties bought the house at a foreclosure auction for $4,400.

Cooke said he contacted a lawyer, but it was too late. He had to move out of his house and into an apartment. In May 2023, the house was resold for nearly $310,000.

Since 2018, the Davis Lake Community Association has filed foreclosure actions against at least 26 of its more than 800 homeowners, state courts data shows.

Delton Russell, the former association president who signed the HOA’s foreclosure authorization form, declined to discuss the decision to foreclose on Cooke — and the HOA’s broader policy on when to foreclose. He no longer lives in the community, he said.

Jim Slaughter, a Greensboro lawyer whose firm has represented hundreds of HOAs, said North Carolina law requires associations to make extensive efforts to notify homeowners about delinquencies before billing them for attorney’s fees, filing liens and foreclosing.

The law doesn’t require that HOAs make contact with homeowners before filing foreclosure actions. But it does require that associations vigorously attempt to notify homeowners about a foreclosure hearing using the same procedures that are used to deliver a summons — either asking a sheriff’s deputy to personally serve the notice or sending it by registered or certified mail or a delivery service such as FedEx.

HOAs that can’t connect with homeowners can fulfill the notice requirements by publishing a legal notice in a newspaper.

“Seldom is it that the person doesn’t know,” said Slaughter, a past national president of the College of Community Association Lawyers.

Attorneys for HOAs also note that state law gives homeowners many chances to pay their debts and thereby prevent foreclosure sales. Ben Karb, a Charlotte attorney who has represented HOAs in many foreclosure cases, notes that homeowners have the opportunity to do that before a lien is filed, before the case reaches foreclosure, and even up until 10 days after the highest bid is placed on the house during a foreclosure sale.

“If the homeowner is trying to do something, then the county clerk will work with them,” Slaughter said.

But while the law requires that HOAs make efforts to notify homeowners, that doesn’t guarantee that owners actually receive notice.

Jim White, a Chapel Hill lawyer who regularly represents homeowners, said he has heard from many who weren’t aware their HOAs were foreclosing on them.

“The number of people who said they weren’t notified is remarkable,” he said.

House Bill 542 would strengthen notification requirements. State law doesn’t currently specify that HOAs must attempt to email homeowners about delinquencies. The bill would change that by requiring that HOAs send delinquency notice and liens to any email address designated by the homeowner.

The bill would also require the court clerks who authorize foreclosures to ask HOAs what efforts they’ve made to communicate with homeowners in an effort to resolve the matter.

But for now, it’s incumbent on homeowners to pay attention and make sure they pay their HOA bills, says James Galvin, a Charlotte lawyer who frequently represents homeowners.

“If you fall asleep on this, they can kick you out of your house,” he said.

A difficult goodbye

Peper, the former southwest Charlotte homeowner, understands that all too well.

During a visit to his former ranch-style house with an Observer reporter, he talked about the workshop he built in his garage, the landscaping he improved, the new hardwood floors he had installed.

“It was perfect for what I needed,” he said, a note of sadness in his voice.

The Steelecroft Place Homeowners Association, his former HOA, never reached out to him to offer a repayment plan before foreclosing, he said.

“Most people have no idea they can do that,” Peper said.

Officials for the HOA’s management company said they don’t discuss foreclosure cases. Robert Dortch, the lawyer who represented the HOA in the foreclosure, did not respond to emails from an Observer reporter who asked about the case.

When homeowners get behind on their dues, Peper contends, HOAs should be able to put liens on their homes and suspend their pool privileges — but not foreclose on them.

“The HOA has all the power in North Carolina,” he said. “I don’t think that’s fair.”

How we reported this story

To investigate HOA foreclosures in North Carolina, The Charlotte Observer and The News & Observer conducted a first-of-its-kind analysis of HOA foreclosures in North Carolina.

News & Observer data reporter David Raynor analyzed a North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts database of all civil cases from January 2018 to June 2023 to identify HOA-related foreclosure filings

Charlotte Observer investigative reporter Ames Alexander then reviewed court files in more than 100 foreclosure cases in Mecklenburg and Wake counties to gather more detailed information on each case.

Alexander interviewed six people who lost their homes to HOA foreclosures and more than 30 others, including attorneys who represent both HOAs and homeowners. And he observed a foreclosure auction at the Mecklenburg County Courthouse.

As part of the data analysis, Raynor discovered that 50,000 liens were filed by nearly 6,000 North Carolina HOAs between 2018 and mid-2023. In roughly 11% of those cases, HOAs started foreclosure proceedings.

To see more details on the analysis, click here.