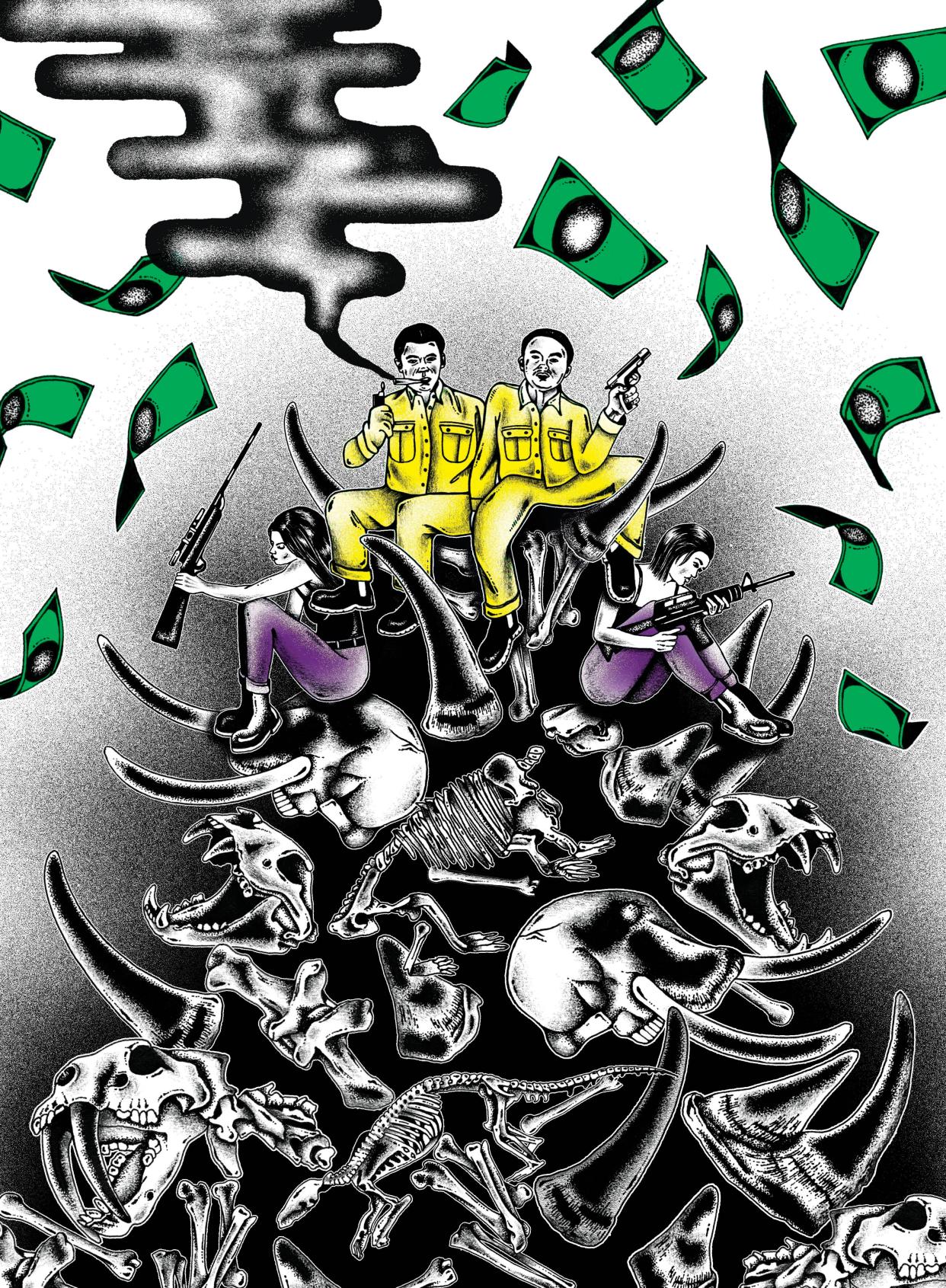

Hunting the Elusive Rhino-Horn Cartel of Thailand

The thunder crack of rifle shot hung for a faint second in the air. Then, with a tremendous tumble, the white rhino hit the dirt. It had taken five bullets to bring the animal down, the final one fired from near-point-blank range. Now, as Chumlong Lemtongthai watched the creature give up its last, pained breaths, he saw only one thing: money.

“Let's go,” he said, instructing his associates to clamber over the corpse, plant themselves astride the head, and remove the animal's twin horns with a few thrusts of a bone saw. Lemtongthai, who'd grown up in Thailand but had made his way to South Africa to strike it rich on hunts like this one, moved deliberately, keenly aware that the work that mattered most to him was just beginning. He knew that a small fortune was his to be won. But first he had to spirit the horns out of Africa and into the hands of his associates in Laos. Once there, they'd be fed down a supply chain that he helped control.

Hitting the black market in China or Vietnam, the horns would be shaved into a fine powder and packaged into tiny vials, and then sold to those who cling to ancient beliefs about their power to heal all manner of maladies—like rheumatism, perhaps, or maybe cancer. The price for such a specious remedy is steep. The rhino dust—sometimes stirred carefully into tea, other times ingested directly—can fetch $65,000 per kilogram. For Lemtongthai, that meant nearly $200,000 for a single horn.

Illicit though his scheme was, there was nothing particularly clandestine about Lemtongthai's behavior out here in the African bush. He motioned for a young lady—a Thai stripper named “Joy”—to approach the dead rhino. Joy had dressed for the hunt in tight jeans and a purple track jacket. She was given the rifle, and she moved in beside the animal, kneeling with the gun in hand. She flashed a wide smile for a waiting camera. It was critical that she appear to be the one who'd bagged the rhino. A photo of Joy and her prize would help with that.

Lemtongthai had been trafficking protected species for a dozen years—but lately had gathered an increasing degree of influence in a vast world of poachers, smugglers, and other merchants of animal death. He'd had a gritty start in life, selling fruit in a street market in Bangkok. But his fortunes turned around when he fell in with a pair of men who dealt in the bones of exotic cats, which can also be ground and are sold in vast quantities. Under their tutelage, Lemtongthai learned the tricks of the tiger-bone trade: procuring the carcasses, boiling them to separate flesh from bone, then wrapping the skeletons in plastic bags and shipping them to a major buyer in Laos for $450 a kilogram.

From there the bones would move east, across the Laotian border into Vietnam, or north, into China. Soon he set himself up in South Africa and used the same techniques to begin moving large quantities of lion bone back to Asia. He was rarely troubled by the government export quotas on lion bone—ranchers and local officials hardly enforced them—and Lemtongthai could earn $1,000 for a bag of bones. He found buyers for even the teeth and claws, which couriers smuggled on flights to Bangkok (thanks, allegedly, to the help of corrupt airline employees).

Lemtongthai drove a Hummer, smoked high-quality weed, gambled in the casinos at Sun City near Johannesburg, and became a regular customer at the Flamingo Gentlemen's Club in Pretoria—a strip club filled with dancers imported from northern Thailand.

Editor-in-Chief Will Welch on GQ's first-ever Summer Beach Reads issue.

But he wanted more. Demand for rhino horn was soaring in Asia, and in 2009 Lemtongthai leapt at the opportunity to expand his business. The work would be risky: South Africa imposed long jail terms for anyone caught poaching or trading the animals. But Lemtongthai knew about a game-changing loophole he could exploit. At the time, under South African law, sportsmen were permitted to hunt one rhino per year and take the head as a personal trophy.

And so it was that Lemtongthai cooked up a simple scheme: He'd hire ringers to pose as trophy hunters, obtain legal export certificates from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and ship the horns to Laos via Thailand. Rather than adorn somebody's wall, they'd be ground down to serve more lucrative purposes.

At first, Lemtongthai flew cronies from home, four or five at a time, to Johannesburg. He made deals with crooked ranch owners, and they in turn hired professionals to do the actual hunting and paid off rangers. Lemtongthai's even believed to have paid off a wildlife quarantine officer at Bangkok's Suvarnabhumi Airport to help ensure that his horns got through without a hitch.

Before long, Lemtongthai hit upon an even more efficient plan: He'd use sex workers and other South Africa-based Thai women instead. One day he showed up at the Flamingo and offered the girls about $500 apiece to join the charade. That's how several of the Flamingo strippers, including Joy, were transformed into the world's unlikeliest big-game hunters. Soon they were regularly shuttling in Lemtongthai's black Hummer from the strip club to a ranch a couple of hours away.

The grim business was booming, until the scheme hit a snag. In February of 2011, customs officials at Suvarnabhumi Airport stopped a package of rhino horns that had become separated from its CITES certificate. When the officials tracked down the document, they took a close look and noticed that the globe-trotting trophy hunter who'd supposedly nabbed this rhino was actually a 20-year-old woman originally from northeast Thailand. That seemed odd.

In all of Bangkok, nobody was more interested in this little customs anomaly than Steve Galster. A shrewd and determined American conservationist, he'd cultivated a cozy relationship with customs officials because he craved this sort of intel. When he was tipped off about the strange package, he knew exactly what was going on.

Galster had moved to Thailand a decade earlier, setting up his own cloak-and-dagger operation to map—and dismantle—the covert market for illegal animal parts. He had zeroed in on the networks that powered the illicit trade, devoting particular attention to an elaborate organization that he had dubbed Hydra, after the multiple-headed sea serpent of Greek mythology. The scheme that Lemtongthai was wrapped up in, Galster figured, looked like a Hydra operation.

The org chart of the Hydra cartel is a map of secrets: a field guide of “who's who in the zoo.”

Run by a handful of powerful gangsters based in Thailand and Laos, Hydra utilized an army of suppliers who would deliver rhino horns, elephant tusks, lion bones, tiger bones, bear bile, the spines of pangolins (anteaters found in dwindling numbers in Southeast Asia and Africa), and other parts harvested from protected wildlife. Hydra also maintained a network of corrupt cops, customs officials, and court officials to facilitate shipments and shield itself from prosecution. Lemtongthai, Galster grasped, appeared to be a major figure in the syndicate.

Indeed, Lemtongthai was feeding brisk demand at the time, according to Galster. On April 23, 2011, Lemtongthai's buyer in Laos placed an order for 50 sets of rhino horns and 300 lion skeletons, which would sell for a total of $15 million. Lemtongthai would clear $1.5 million on the deal.

While Galster was focused on Lemtongthai, officials in South Africa were gathering evidence on the staged hunts, too. In November 2011, as Lemtongthai stepped off a flight from Bangkok, cops stopped the trafficker at the airport. “We found [incriminating] documents and computer files, along with photos of dead rhinos he was posing with,” a South African investigator, Charles van Niekerk, told me. Faced with evidence compiled by both van Niekerk and Galster, Lemtongthai pleaded guilty to running the scam and was sent to prison for six years. For Galster, this victory was just the start. Determined to work up the shadowy Hydra chain, he paid close attention to the scurrying chaos and reorganization set off within the syndicate by Lemtongthai's capture. Galster wasn't going to rest, he vowed, until he had killed Hydra completely.

The nerve center of Steve Galster's operation is tucked inconspicuously into a back alley in central Bangkok, in a low-slung villa. The building's tranquil courtyard features a turtle-filled pond and a garden shaded by lush palms and hardwoods. Inside, where his Freeland Foundation does business, the mood is less serene.

In one windowless office, Galster's obsession is splayed across an entire wall—a tangled collage of data that represents the organizational structure of Hydra. Looking something like John Nash's wall of feverish scribblings in A Beautiful Mind, the diagram has taken Galster years to assemble and has required the service of high-powered analytic software as well as old-fashioned covert sleuthing. It's a blizzard of headshots, birth dates, maps, government ID numbers, biographical text blocks, and hundreds of crisscrossing lines that delineate pecking orders, family relationships, and criminal connections. It's a map of secrets: a field guide, Galster says, of “who's who in the zoo.”

The giant dossier is deadly serious for Galster. “They are mass, serial murderers,” he tells me. By way of example, he points to the rise in rhinos slaughtered in South Africa in the past two decades—from 13 in 2007 to 83 in 2008 to 1,028 in 2017, an average of nearly three a day—a spike that he attributes in large part to Hydra. “These guys are laying waste to the world's most iconic and precious species for a ton of money,” he says.

While the pace of the slaughter has quickened, the demand in Asia for illicit animal parts is nothing new. Ancient Chinese medical texts are replete with references to the medicinal properties of rhino horn, tiger bone, anteater scales, and bear gallbladders. Some of the powers are purely imaginary: The keratin that composes a rhino's horn has no proven medical value. Other products have uses a bit more grounded in science. Bear bile is rich in ursodeoxycholic acid, which is useful for treating liver and gallbladder conditions.

Scientific or not, the trade in animal parts has grown more complex. The market for tusks, bones, and pangolin scales—which are all hard, durable products that can be stashed away for years—now includes savvy commodities brokers who hold them in hopes of making big profits when prices spike.

For many wealthy elite in China and Vietnam, the reputed health benefits are almost beside the point. The products have become status symbols, hauled out at parties and business meetings—markers of taste and sophistication. And a fast-rising middle class in both countries is increasingly fueling the trade.

The effects have been devastating. Aside from the well-documented mass slaughter of Africa's rhinos and elephants, Asian tigers have declined from 100,000 over a century ago to fewer than 4,000 today, while the rhino population in Asia has plummeted to the brink of extinction during the same period. And the cruelty is near unimaginable: Bear bile “farmers,” who operate throughout Southeast Asia, often insert catheters into a captive live animal, a frequently agonizing procedure, to extract the precious fluid from its gallbladder. Sometimes traffickers save themselves the trouble and just kill the bear outright, cut out the organ for onetime use, and ship it on ice.

The Thai government has long known about the abuses, but for many years it turned a blind eye to them. “There have been no rewards, no bonuses, no incentives for fighting wildlife crime in Thailand,” Galster says. “Police would rather work in counternarcotics or counterterrorism. We're trying to change that.”

The Freeland Foundation routinely shares information and resources with the police. To a degree that's rare among public and private organizations, they even work together on tough cases.

Galster is 57 and speaks in the flat tones of a native midwesterner. He wears a no-nonsense expression and tends to move along in big, loping strides, as if he always has somewhere important to get to. On a recent afternoon, he introduces me to two ex-narcotics agents on his staff: There's “General Eddy,” who became famous in law-enforcement circles for arresting the fugitive Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout in 2008. Next I shake hands with “Poolsub,” who helped gather the evidence that put Chumlong Lemtongthai behind bars. In addition to the two dozen people working here in Bangkok, Galster also employs former military and law enforcement scattered around Southeast Asia—including “Nile,” a secretive character fluent in Vietnamese, whom I would later encounter at a beachside safe house and who has spent thousands of hours gathering surveillance photos and video footage of key Hydra players.

Galster's first glimpse at the highest rungs of Hydra leadership came over a decade ago. A wealthy and secretive Thai woman, whom Galster has never named, led him to a pair of poachers whom she persuaded to divulge their secrets. The men, Galster says, pointed to the figure who stood atop the organization: Vixay Keosavang, a former Laotian military officer. Soon after, Galster learned the identity of Keosavang's closest friend and alleged partner in crime: Bach Van Limh, a burly, gregarious Vietnamese immigrant to Thailand.

The two men lived opposite each other on the Mekong River—Bach on the Thai side, Keosavang in Laos. Bach's alleged expertise was in slipping contraband into the country. “He had people based at ports and airports; he had people in northern Thailand and in southern Thailand,” Galster says. “He had smugglers, people within the private sector, and government officers on his payroll.”

Keosavang, for his part, excelled in actually moving the product throughout Asia after it landed in Laos. He was aided in this enterprise, Galster says, by the import-export firms he ran across the river from Bach—legal businesses that are thought to have helped function as clearinghouses for illegal animal parts. He also owned several grim “zoos” in Laos, private menageries where an assortment of animals were raised for slaughter. Here, tigers, macaques, and other animals were allegedly held and then processed for shipment.

At the height of their business, around 2013, Keosavang and Bach Van Limh were said to be moving some 300 tons of wildlife parts a year—including 100 tons of live turtles, 100 tons of live snakes, 3 tons of lion and tiger bones, 75 tons of pangolin scales, and unknown quantities of elephant tusks and rhino horn. They were earning millions of dollars each year and using the proceeds to buy houses, hotels, expensive vehicles, and frequent trips together to Pattaya, the Thai beach resort famed for its sex industry.

But around 2014, Vixay Keosavang faded from the scene, seemingly done in by negative publicity from the arrest and guilty plea of Chumlong Lemtongthai, the architect of the faux rhino hunts in South Africa. That year, Galster says, Bach Van Limh also abruptly dropped out of view, returning to northern Vietnam. Perhaps he felt the walls beginning to close in. But wildlife contraband was still moving through the usual routes, leaving Galster to wonder: Who could be running Hydra now?

One night in Nakhon Phanom, where authorities were surveilling a group of suspected drug traffickers, an agent broke into the trunk of a suspect's vehicle. As he did, he caught the odor of urine and animal parts—a sign that the group might be moving wildlife as well. Galster was shown surveillance photos of some of the suspects and their associates, he says, and ran their names. They matched those of traders who had worked with Chumlong Lemtongthai. Galster also noticed something familiar in the photos, specifically the eyebrows and facial features of one of the men: He looked remarkably similar to the exiled Bach Van Limh.

In their bid to determine who was in charge of Hydra, Galster's team had, for months, been circling six shadowy figures. They all appeared to have overlapping friendships and business connections with one another. Curiously, the men also had similar names—Boonteung, Boon Chai, Mai Bach, Wanchai Bach, Bach My, and Chai. After analyzing Facebook data, depositions, and these new surveillance photos, Galster realized, in 2015, that he wasn't, in fact, chasing six ghosts. He and his team were pursuing only one. The names were aliases of a single person: a baby-faced resident of Nakhon Phanom named Boonchai Bach. He was the younger brother of Bach Van Limh—and he had apparently been anointed as his successor. “It was a ‘holy shit’ moment,” Galster says.

In addition to his profligate use of aliases, the younger Bach was a master of covert tradecraft. According to Galster, he fastidiously kept his name off bank accounts and property records, frequently changed his appearance, refrained from calling other members of the syndicate on his cell phone, and kept such a low profile that beyond his family, virtually nobody in Nakhon Phanom—a city roughly the size of Seattle—was aware of his existence. “He knew what he was doing,” Poolsub, the former Thai police officer, told me. Hunting Boonchai Bach wouldn't be easy, but bagging him, Galster knew, could upend Hydra.

Soon agents were scouring Nakhon Phanom, hunting for Boonchai Bach's headquarters. They cruised up and down the riverfront until they noticed something: a four-story residential structure that appeared to have an unusual security grille around the upper floors that obscured what was going on inside. The team surveilled the building and quickly spotted Boonchai Bach. They watched in the middle of the night as goods were loaded by henchmen, whom they followed to warehouses, hotels, and other properties. They identified a fleet of expensive vehicles that Bach used to travel back and forth across the Thai-Laotian border. But they couldn't catch him in a criminal act.

Then, on December 11, 2017, after two years in pursuit, Galster says, customs agents at Bangkok's Suvarnabhumi Airport received an alert that a Chinese national suspected of being a courier for wildlife traffickers would be arriving on a flight at noon. The customs men intercepted his suitcase before it reached the carousel—and found, wrapped in plastic, 14 rhino horns cut into 65 pieces. The shipment had a street value of more than $1 million. The officers sent the luggage along to baggage claim and waited to see what would happen next. They watched the Chinese man pluck the suitcase off the carousel and then stroll to the nearby office of Nikorn Wongprajan, a longtime airport quarantine officer. This was strange, they thought. The agents hustled over to Wongprajan's office, and there, stashed inside a locker, was the rhino horn.

Wongprajan—panicky and desperate to spare himself—agreed to help the police continue to follow the horn. The authorities trailed Wongprajan, and watched as he passed the package to one of Boonchai Bach's relatives. The cops swooped in.

About a month later, General Eddy and Poolsub interviewed Wongprajan at Samut Prakan Prison, on the outskirts of Bangkok. An officer accompanied them. At first, Wongprajan denied any connection to Hydra, says Galster. Then Poolsub pulled out photos obtained by Freeland showing Wongprajan and Chumlong Lemtongthai together beside a dead rhino in the bush. Wongprajan, it looked like, had been Lemtongthai's crony and plant at the airport—expediting delivery of rhino horns from the fake hunts in South Africa to Bangkok. With Lemtongthai in prison, Wongprajan had allegedly established new relationships in Hydra. “We know you know this guy. You went to South Africa to see him,” Poolsub said. Wongprajan confessed. Then Poolsub showed him a photo of Boonchai Bach.

“Do you know this guy?” he asked.

Wongprajan nodded.

“Was this the guy you were selling rhino horn to?” the officer pressed.

“Yes,” he replied.

“Write it down.”

According to Galster, Wongprajan scribbled a note naming Boonchai Bach as the sponsor of the rhino-horn-smuggling operation—and signed Bach's photo. “I've got what I need,” the officer said. Then he issued a warrant for Boonchai Bach's arrest.

On the afternoon of January 18, 2018, Thai provincial police apprehended the suspected Hydra kingpin near Nakhon Phanom and shipped him to Bangkok. Soon, likely dazed and in disbelief, Bach found himself inside a cell at Suvarnabhumi Airport, charged with wildlife trafficking.

Steve Galster received the news about Bach's arrest via a WhatsApp message while in England on a fund-raising trip. You've got to be shitting me, he thought, reading the text. All along, Galster had feared that the layers of protection surrounding Bach were impregnable, that the corruption and apathy of Thai government officials were too deeply ingrained to break through Bach's impunity. But now, against all odds, it seemed like the central pipeline had been ruptured. And with Nikorn Wongprajan prepared to swear at trial that he had been acting under Bach's orders, it looked like the supposed Hydra boss was going away for a long time. Galster had every reason to celebrate.

One warm evening earlier this year, I went with Galster to northeastern Thailand, to the epicenter of Hydra's illicit empire in the river town of Nakhon Phanom. At night, from the bank of the Mekong, we could hear the pulsing of pop music across the water, in Laos. I could also make out the putter of a motorized longboat slipping through the currents carrying who-knows-what—tiger parts, maybe, or methamphetamines or any of the innumerable commodities that journey stealthily through this part of Asia under the cover of darkness. “They always move at night,” Galster said.

Shortly before we arrived in Nakhon Phanom, Wild Animals Checkpoint agents just down the river in Mukdahan seized 182 baskets containing 2,730 rat snakes and cobras as they were about to be ferried out of Thailand and into Laos.

While we moved along the city's riverfront promenade, Galster pointed out Bach's apartment building, which is believed to have provided convenient accommodations to South African lion-bone dealers when they're in town. Galster says it also contains a back room that has played host to Hydra's meetings, making the operation the Nakhon Phanom equivalent of The Sopranos' Satriale's Pork Store. “All the Hydra players own hotels and resorts,” said Galster. “They're money-laundering machines.” Just down the street stands a bar owned until recently by Bach. A short drive from the center of town is the police station where a surveillance team observed Boonchai Bach's suspected bagman, making regular drop-offs in a zipped canvas sack.

The milieu is a natural one for Galster, who has spent his career investigating the illicit trade of drugs, arms, wildlife, and human beings. Raised in Wisconsin, Galster attended George Washington University in the 1980s and became interested in the Soviet war with Afghanistan. After graduation, he landed a job with an NGO that took him to the front, where he documented soldiers and Afghan mujahideen selling heroin to finance weapons purchases. Galster realized that opportunities abounded for a guy looking to mix high ideals with a taste for adventure.

In the early 1990s, he went undercover and joined Christian fundamentalists who were flying guns and Bibles to a rebel group in Mozambique. The dissidents were backed by the apartheid South African government, which was trying at the time to reopen the ivory trade. But the intelligence gathered by Galster and a colleague helped to derail the effort.

Two years later, Galster and another colleague, posing as his wife, infiltrated a trafficking gang in Zhanjiang, in southern China, where he earned the trust of dealers who showed off a stockpile of 500 rhino horns. He filmed the encounter, and before long, police in China swept up the gang, seized the horns, and burned the entire stock on live TV.

In 1994, Galster began investigating a litany of atrocities—cockatoo and scarlet-macaw trafficking in the Amazon, tiger poaching in the Russian Far East and Central Asia. If there were cartels threatening to wipe out animals, Galster made it his business to stop them.

In Thailand, in 2003, he met the turncoat poachers who showed him how the elaborate business worked—tracing for him the supply lines that led into Laos and then onward to Vietnam and China. “It was a free-for-all,” says Galster. “The attitude among traffickers was ‘Get it to Laos and we'll be fine.’ ”

That was the first time that Galster ever heard of Keosavang, the former military officer thought to be running Hydra. He quickly learned that the operation wasn't just relying on parts shipped from places like Africa. One of Hydra's suppliers, Galster discovered through informants, was the Tiger Temple, a zoo and meditation center near the famed bridge over the River Kwai in Kanchanaburi, Thailand. Western tourists flocked to the zoo to pet tiger cubs, learn mindfulness techniques, and walk along footpaths through the woods. Meanwhile, the Buddhist monks in charge were secretly spiriting live big cats to Laos. When Thai authorities shut down the Tiger Temple in 2016, they reportedly seized about 150 live tigers, the thawed carcasses of 40 dead cubs, 20 cubs in jars of formaldehyde, two tiger pelts, and 1,500 tiger-skin amulets.

Another suspected provider in what Galster was beginning to regard as the Hydra network was Daoreung Chaiyamat, who owned a wild-animal farm, the Star Tiger Zoo, in central Thailand. With the local police thought to be in her pocket, Galster says, she could dispatch trucks and boats to Hydra, shipments filled with tigers, as well as pangolins, turtles, snakes, ivory, and more. Freeland launched an investigation in 2009 that eventually helped police freeze $36.5 million of Chaiyamat's assets—including the tiger farm, houses, hotels, jewelry, cars, and cash. Photos obtained by Freeland showed Chaiyamat posing gleefully with a straw basket stuffed with Thai cash, and a toddler napping beneath stacks of Thai cash and American $100 bills.

The scene at the Sriracha Tiger Zoo is degrading and depressing: Tourists dangle raw chickens from fishing poles over a bleak pen where the cats snarl and fight for the food.

Although no criminal charges for animal trafficking were ever brought against Chaiyamat, Galster's research into her and her cohorts provided him with key insights into how the Hydra gang moved its product. He learned, for instance, that pangolin scales, easily mistaken for wood chips, are often smuggled inside potato sacks, while tiger and lion skeletons are frequently disassembled and crammed, skulls and all, into plastic body bags. (The putrid—and telltale—scent of lion and tiger bones can become an occupational unpleasantry for those who smuggle them.)

Rhino horn, hard as a block of wood, can be flown in suitcases or duffel bags—traveling either intact or chopped into pieces that get wrapped in tinfoil or bubble wrap and then surrounded by shampoo bottles or deodorant to mask the foul odor.

Elephant tusks travel in all sorts of ways: inside tin containers labeled “telecommunications equipment,” in hollowed-out logs at the bottom of a shipment of timber.

Some of the contraband reaches Thailand by cargo ship before journeying to Laos and onward to points north. To get it across the Thai border, the product is either hauled by truck across the handful of bridges on the Mekong River or packed onto what Galster calls “banana boats,” wooden longboats with a single outboard motor, and ferried through darkness.

“This is the mother ship of the zoos,” Galster tells me as we pull into the parking lot of the Sriracha Tiger Zoo, a popular tourist attraction and reputed big-cat-laundering center. We're two hours south of Bangkok, near the seaside city of Pattaya, a favored hangout for the Hydra gang.

For years, the Sriracha Tiger Zoo has appalled Galster. He claims that sources familiar with what goes on inside have painted a harrowing picture of slaughter.

He says he was told that after tigers outlived their usefulness, butchers routinely knocked out the beasts with powerful drugs, slit their throats and dismembered them, then packed the pieces into vehicles for transport to Laos. The zoo always kept about 500 tigers on hand, one source told him, so that nobody would notice if a few went missing. The place was under police investigation for a while, but the attention faded away. Still, Galster suspects the zoo may be laundering tigers. Demand for tiger parts remains strong in Vietnam and China; the hottest new product on the market is a supposed aphrodisiac, extracted from the bones and sold in capsule form for $300 per pill.

Near midnight, in the heart of the city's red-light district, Steve Galster ducks into three clubs in rapid succession—hoping to pick up clues about the syndicate's latest activities.

We follow walkways lined with flowering trees, past throngs of tourists, almost all of them Chinese. The scene was degrading and depressing: At the Shoot 'N' Feed attraction, young men armed with pellet guns attempted to bring down chunks of raw meat suspended in tin boxes over a stark concrete enclosure filled with hungry, pacing adult tigers. Farther down the path, tourists dangled raw chickens from fishing poles over another bleak pen containing a dozen more of the huge, beautiful animals. To the delight of their tormentors, the cats snarled and fought one another for the food. Undercover investigations by wildlife advocates here and at a similar zoo in Thailand have produced videos that show what tourists apparently come to experience: chained tigers being forced to roar for photos, cubs separated from their mothers being bottle-fed by visitors.

Such zoos have been able to flourish in Thailand because of the wealth and political influence of those who run them—and the hopelessness of the public. “You don't have people power here,” Galster tells me. “You've got corrupt rich people getting away with it.” Nobody knows exactly how many tiger “sanctuaries” exist in the country, and it took a massive media campaign, including an investigative article in National Geographic, to prod the government in 2016 to shut down the Tiger Temple.

Later that night, Galster tells me that there's another piece of business he wants to check on while he's in Pattaya. He's been trying to track down a target he refers to as “Jayhawk,” a top Hydra associate who has dropped out of sight for months. Galster knows that Jayhawk is an enthusiastic patron of the beach town's tawdry sex clubs, favoring several bars and strippers in particular. Galster, who speaks Thai and knows the scene well, is hoping to find out whether Jayhawk has changed his patterns—and perhaps pick up clues about the syndicate's latest activities.

The taxi drops us off near midnight on Walking Street, the heart of the red-light district. Galster ducks into three clubs in rapid succession, each with a similar motif: a dozen Thai women dancing desultorily to techno music on a mirrored stage beneath strobe lights, surrounded by libidinous foreigners. At the fourth, after making inquiries with the bar hostess and the girls, Galster finds the woman he's looking for: “Doll,” one of Jayhawk's regulars. She's emerged from the dressing room and perches on a stool beside him. She's skinny, wears braces, and looks to be about 16. In a whisper, Galster tells me she's in her 30s. “She had the orthodontia to make herself look young,” he tells me.

Galster and Doll make small talk in Thai, and then he cuts to the chase: “Has the big, scary-looking Vietnamese thug who likes you been around lately?” he asks.

“Yeah, we were together last weekend,” she replies. He was here with a younger friend, Doll tells Galster.

As we head for the door, Galster tells me that he'll try to identify the young companion through his police contacts. But he's gleaned one important fact from the encounter with Doll: Jayhawk is back in the game.

After cops hauled Boonchai Bach off to jail in 2018, Hydra appeared derailed. Conservationists around the world cheered the development. Bach faced charges of rhino-horn trafficking and was eyeing four years in prison if convicted.

As the trial began last year in a provincial courtroom in Samut Prakan, Bach's lawyers insisted that their client was a victim of mistaken identity, Galster recalls. The prosecution, seemingly short on initiative, decided to rely predominantly on the testimony of its star witness, Nikorn Wongprajan, the airport quarantine officer. As long as he stuck to his story and told the court what he had already told cops—namely, that he'd been a key cog in a Bach-hatched scheme to move horns through the airport—the man believed to be running Hydra would end up in prison.

Galster is still chasing the man who he suspects sits atop the Hydra cartel. But he's trying a new approach—a Hail Mary attempt to appeal to the smuggler's conscience.

But when it came time for Wongprajan to identify the head of the organization, he refused to point at Bach, seated in the defendant's chair. Maybe he was thrown off by Bach's changed appearance—he had let his hair grow out and wore glasses. But it might have been out of pure fear. “I'm not sure,” he said nervously. “I don't know who this guy is.” On January 29, 2019, as Galster and Poolsub looked on in dismay, the judge dismissed all the charges. The suspected Hydra boss was immediately hustled out of the courtroom by two escorts, one of whom veered off and took Poolsub aside.

“I remember you,” he said in a faux-polite tone.

“Oh yeah? How's that?” Poolsub shot back.

The two men exchanged a few more tense words. Then the escort slipped into a vehicle with Bach and drove away.

After that, Bach disappeared from circulation. Meanwhile, Wongprajan was returned to a jail cell to await his own trial for his role in the rhino-horn scheme. Galster wasn't shocked. “They either threatened Wongprajan or promised him money,” he says.

Galster is still chasing Boonchai Bach. But he's refraining, for now, from trying to put him behind bars. Instead he's testing a new approach—a Hail Mary attempt born of frustration. During our stopover in Nakhon Phanom, Galster wrote a message to Boonchai Bach on Freeland letterhead. The note, a quixotic appeal to the smuggler's conscience, invited him to contribute to Project RECOVER, an initiative recently put together by Freeland and IBM. It aims to use confiscated funds from traffickers to set up programs that help beleaguered populations of elephants, tigers, rhinos, and other wildlife recover from poaching. “We would like you to consider joining this program,” Galster wrote in Thai. “Here is a chance to be on the right side.”

Galster dropped the letter with a clerk at the reception desk at Bach's apartments on our way to Nakhon Phanom airport. Three months later, he is still waiting for a reply.

Joshua Hammer wrote about a Ukrainian assassination mystery in the March 2018 issue of GQ.

A version of this story originally appeared in the June/July 2019 issue with the title "Hunting The Rhino-Horn Cartel."

Originally Appeared on GQ