Hurricane Laura slams into Louisiana, forecasters warn of wall of water

By Ernest Scheyder and Brad Brooks

PORT ARTHUR, Texas (Reuters) - Hurricane Laura made landfall early on Thursday in southwestern Louisiana as one of the most powerful storms to hit the state, with forecasters warning it could push a massive wall of water 40 miles inland from the sea.

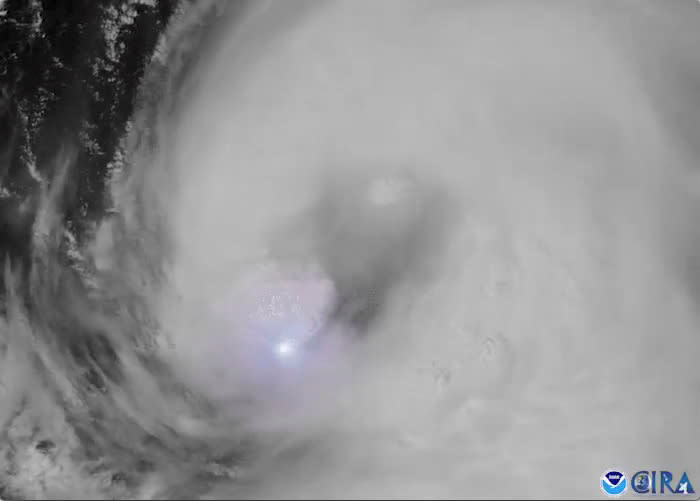

Laura made landfall just before 1 a.m. as a category 4 storm, packing winds of 150 mph (240 kph) in the small town of Cameron, Louisiana, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) said.

"The eyewall of Laura will continue to move inland across southwestern Louisiana during the next several hours," the NHC said in a early Thursday bulletin. "TAKE COVER NOW!"

The bulletin added that Lake Charles, Louisiana, was seeing sustained winds of 85 mph (137 kph) and gusts up to 128 mph (206 kph), in the hour after landfall.

Officials across the hard-hit area said it would be several hours before they could get out to begin search and rescue missions. Downed trees blocking roadways were expected to be the biggest immediate challenge for rescuers.

In Vermilion Parish, just east of Laura's landfall, the sheriff's office gave a stark warning to residents before the storm hit. "If you choose to stay and we can't get to you," read a statement on the sheriff's Facebook page, "write your name, address, social security number and next of kin and put it a ziplock bag in your pocket."

VODKA AND SHELTER

Hurricane-strength winds could blow as far as 200 miles inland to Shreveport, Louisiana, forecasters said.

The oil-refining town of Port Arthur was just west of where Laura made landfall. The city of 54,000 was a ghost town late on Wednesday, with just a couple of gas stations and a liquor store open for business.

"People need their vodka," said Janaka Balasooriya, a cashier, who said he lived a few blocks away and would ride out the storm at home.

The area where Laura made landfall is marshy and particularly vulnerable to the storm surge of ocean water.

"This is one of the strongest storms to impact that section of coastline," said David Roth, a forecaster with the National Weather Service. "We worry about that storm surge going so far inland there because it's basically all marshland north to Interstate 10. There is little to stop the water."

Just hours before Laura smashed into the coast, Port Arthur resident Eric Daw hustled to fill up his car at one of the few gas stations still open.

He said he had wanted to evacuate earlier but lacked money for gas as he was waiting on a disability payment. Daw was headed to a shelter in San Antonio, a 4-1/2-hour drive, where instead of worrying about the storm he has to contend with COVID-19, echoing concerns of many others.

"They say we are all supposed to socially distance now," he said. "But how am I supposed to socially distance in a shelter?"

'WALL OF WATER'

About 620,000 people were under mandatory evacuation orders in Louisiana and Texas.

The storm surge could penetrate inland from between Freeport, Texas, and the mouth of the Mississippi River, and could raise water levels as high as 20 feet (6 meters) in parts of Cameron Parish, Louisiana, the NHC said.

"To think that there would be a wall of water over two stories high coming on shore is very difficult for most to conceive, but that is what is going to happen," said National Weather Service meteorologist Benjamin Schott at a news conference. Most of Louisiana's Cameron Parish would be under water at some point, Schott added.

Temporary housing was hastily organized outside the surge zone for evacuated residents, and emergency teams were being strategically positioned, state and federal emergency management agencies said.

Laura was also expected to spawn tornadoes on Thursday over Louisiana, far southeastern Texas and southwestern Mississippi and drop 5 to 10 inches (127 to 254 mm) of rain over the region, the NHC said. It said there would likely be widespread flooding from far eastern Texas across Louisiana and Arkansas.

Big hurricanes like Harvey and Katrina have previously wreaked havoc on the oil industry sites dotting the Gulf Coast, where nearly half of the United States' oil refining capacity is located. There are concerns Laura may do the same.

When Harvey struck in 2017 there were oil and chemical spills, along with heavy air pollution from petrochemical plants and refineries.

"The storm and the direct damage and human life are the most important things, but pollution can be a double whammy and compound the risk to the community," said Luke Metzger, executive director of Environment Texas.

(Reporting by Ernest Scheyder and Julio-Cesar Chavez in Port Arthur; Jennifer Hiller and Gary McWilliams in Houston; Liz Hampton in Denver; Gabriella Borter in New York and Brad Brooks in Lubbock, Texas; Writing by Gabriella Borter and Brad Brooks; Editing by Leslie Adler and Stephen Coates)