Hurricane Lee's projected path to bring big surf, dangerous currents to US East Coast

As a lifelong surfer, Josh Wagner always appreciated the swells from distant hurricanes off Florida’s coast that can bring in clean, beautiful, rolling waves.

As a beachfront homeowner on the state’s Atlantic coast – who might have lost his home south of Daytona Beach without hopping on a tractor in the middle of the night during Hurricane Nicole last fall – he now fears the erosion and destruction a hurricane can bring.

Hurricane Lee could be the worst of both, Wagner told USA TODAY. Its waves are forecast to be choppy, lousy for surfing, and come with a high risk of rip currents. Any big, rough waves could rip away the little bit of sand that returned to the beaches near Ponce Inlet since Nicole.

Similar fears will ripple northward along the entire Atlantic coast this week. Lee is forecast to move northward parallel to shore a few hundred miles to the east, bringing huge waves and hazardous surf from Florida to Maine.

As of Monday evening, the hurricane maintained its "major" Category 3 status, with sustained winds of 115 mph. and its hurricane-force winds widened considerably, now up to 75 miles from the center.

Though the significant winds are likely to stay offshore for most of the U.S. coast, rip currents and dangerous surf are expected, according to the National Hurricane Center and National Weather Service offices along the coast. Bigger waves and rip currents already have begun to reach East Coast beaches, the weather service said Monday, and that's only expected to increase.

"It’s going to produce a tremendous amount of energy in the ocean in the form of traditional ocean waves," Jamie Rhome, the hurricane center's deputy director, told USA TODAY. “When that energy strikes the coast, it produces this huge rip current risk.”

Where is Hurricane Lee right now?

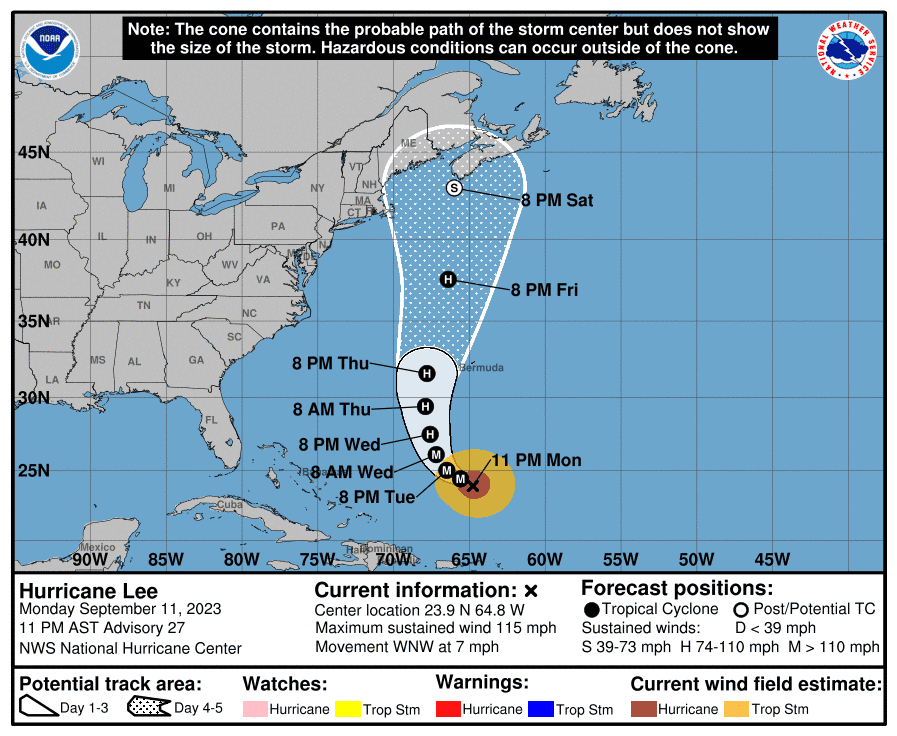

At 11 p.m. Monday, Lee remained a major hurricane, with 115-mph winds.

The storm was about 580 miles south of Bermuda and 410 miles north-northwest of the northern Leeward Islands, moving west-northwest at 7 mph.

A Saildrone – one of several deployed in the ocean along Lee's path – 40 miles south-southeast of Lee's center reported a sustained wind speed of 77 mph and a gust of 105 mph, the hurricane center said Monday at 11 p.m.

A buoy between Lee and San Salvador Island in the Bahamas reported significant wave heights of 17.7 feet.

Lee is forecast to strengthen to 120 mph winds overnight Monday, then begin weakening as it's buffeted by wind shear later in the week and encounters areas of colder water left by hurricanes Idalia and Franklin.

What is the hurricane's path? Will Lee hit the Northeast or Canada?

It's too soon to know how Lee might affect the northeastern U.S. and Canada's Atlantic coast, the hurricane center said Monday, especially because the hurricane is expected to slow considerably.

Hurricane Lee is forecast to make a gradual turn to the north by Wednesday and pass between the U.S. mid-Atlantic and Bermuda on Friday.

Lee could bring strong winds, rainfall, and high surf impacts to Bermuda later this week.

In Maine and along the coast of New England, the National Weather Service said Monday that the "track, intensity, and impacts (if any) from Lee remain uncertain."

The hurricane center's track forecast cone calls for the center of Lee to be offshore somewhere between the coast of New England and southeast of Nova Scotia on Saturday night.

As of 11 p.m., much of eastern New England was in the "cone of uncertainty" in the hurricane center's forecast map for Lee. This includes a portion of the Boston metro area, along with Cape Cod and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket.

"Dangerous surf and life-threatening rip currents" continue to hit the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico and the Bahamas and will affect most of the U.S. East Coast this week as Lee grows and moves northward.

What's the rip current concern?

Rip currents are particularly worrisome for weather officials because 2023 has already been a deadly year: At least 75 deaths are thought to be attributed to rip currents and hazardous surf conditions, the third-highest year since record-keeping started in 2002.

A report published by the American Meteorological Society in August concluded the percentage of direct fatalities attributed to tropical-cyclone-related rip currents has doubled. The authors found:

Direct fatalities during tropical cyclone landfalls rose from 6% from 1963-2012 to 15% from 2013-2022.

Fatalities often occur one or two at a time from distant storms hundreds of miles offshore.

Florida, North Carolina and New Jersey experienced the highest number of tropical-cyclone-related surf and rip current deaths.

“The reason rip currents are so deadly is because all the other hazards in a hurricane have a visual cue,” Rhome said. “Even if you don’t believe the forecasters, you’ll believe your own eyes.

"The air surrounding a hurricane sinks, and that sinking air creates cloud-free conditions and warm days,” he said. “That’s near-perfect beach weather. People flock to the beach and there’s no visual clue that anything is wrong. There’s nothing to see that may tell you you need to be cautious."

Wagner said rip currents seem to be more prevalent in the soft sand offshore since the hurricanes. He advises people enter the water near lifeguards.

"People think this beautiful beach is safe, and it’s not," Wagner said. "People don’t respect Mother Nature. You’re in the ocean, you’re not in a pool."

What's the forecast for Lee along the coast?

Swells from Hurricane Lee already are arriving between Florida and North Carolina.

Melbourne, Florida: "Surf will become increasingly rough as larger breaking waves arrive later this week."

Wilmington, North Carolina: Surf heights could reach 5 feet by Monday afternoon and will "continue increasing the next several days."

Outer Banks, North Carolina: Seas will be "a very dangerous 10-15 feet during the day Friday," gradually subsiding through the weekend. There is a potential for "significant beach erosion, ocean overwash and coastal flooding."

Sep 11, 11 AM EDT | Major Hurricane Lee peak seas near the center are ~48 ft!

Large swells associated with Lee will move through the Caribbean Passages & into the Caribbean waters between the Leeward Islands & the Mona Passage today through Thu. pic.twitter.com/8dlnSu9QvR— NHC_TAFB (@NHC_TAFB) September 11, 2023

What to do if you’re caught in a rip current:

"These rip currents grab and your first primal reaction to that is to swim back to shore. That’s hard-wired to your brain,” Rhome said. “Unfortunately the rip current is harder than people can swim. Most people can swim and swim and swim and can't overpower the rip current.

"Your only option is to swim parallel to the shore and try to get out of it,” he said. The other option is to relax and float until you're out of the current.

What’s next?

It’s not just this storm that worries Wagner. It’s the other storm the hurricane center is watching off the west coast of Africa, which already has surf forecasts calling for 20-foot swells in about two weeks.

“If we get hit by another storm, we’ve got no defense,” said Wagner, an attorney and former county councilman. Communities along the beach between Daytona Beach and Ponce Inlet were hit hard by Hurricane Ian and then by Hurricane Nicole.

Wagner’s family lost their backyard and a sea wall, which they've since been able to replace. Because the sand loss revealed his property had a coquina rock revetment, he was able to get a state permit to add rock to the wall.

They have not been able to replace the 11-foot elevation of sand and dune behind their home they lost during the two hurricanes. Others along the stretch of beach haven't been able to replace sea walls or add rock and some lost homes.

“Up until November I used to look at storms and get excited … for people like me that experienced this for the first time ever, it really changes you.”

His entire beachfront community is at risk if they get a slow-moving storm or a couple of storms, he said. "This storm could be really, really catastrophic."

Whatever storm hits, we're going to be punched "like Mike Tyson fighting Evander Holyfield," he said.

Contributing: Doyle Rice, USA TODAY

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Hurricane Lee's path uncertain in Northeast; rip currents a concern