As hurricane season approaches, experts say to beware of more rapidly intensifying storms

Maggie and Mike McKinney, their pets and a friend sought refuge in a bathroom of their home in Florida’s Panhandle on Oct. 10, 2018 with three shot glasses and a bottle of Jameson Irish whiskey.

They fled there when Hurricane Michael’s fiercest winds arrived and Maggie could feel their house and central brick fireplace swaying. The storm pummeled their century-old home in Econfina, north of Panama City, for about three hours, ripping away pieces of roof and allowing rain to pour in.

When it was over, the home was still standing. The Jameson bottle was almost empty.

They looked out the front door and Maggie spoke three words: “Oh, my God.”

Every tree was twisted, mangled, or ripped from the ground. "The smell of destruction" – a stench she’ll never forget – hit them from the crushed leaves and bark, tree sap and overturned earth.

Lifelong Floridians, the McKinneys had ridden out many hurricanes over 46 years of marriage, but this one was more intense than anything they’d ever seen and far worse than they expected 30 miles inland.

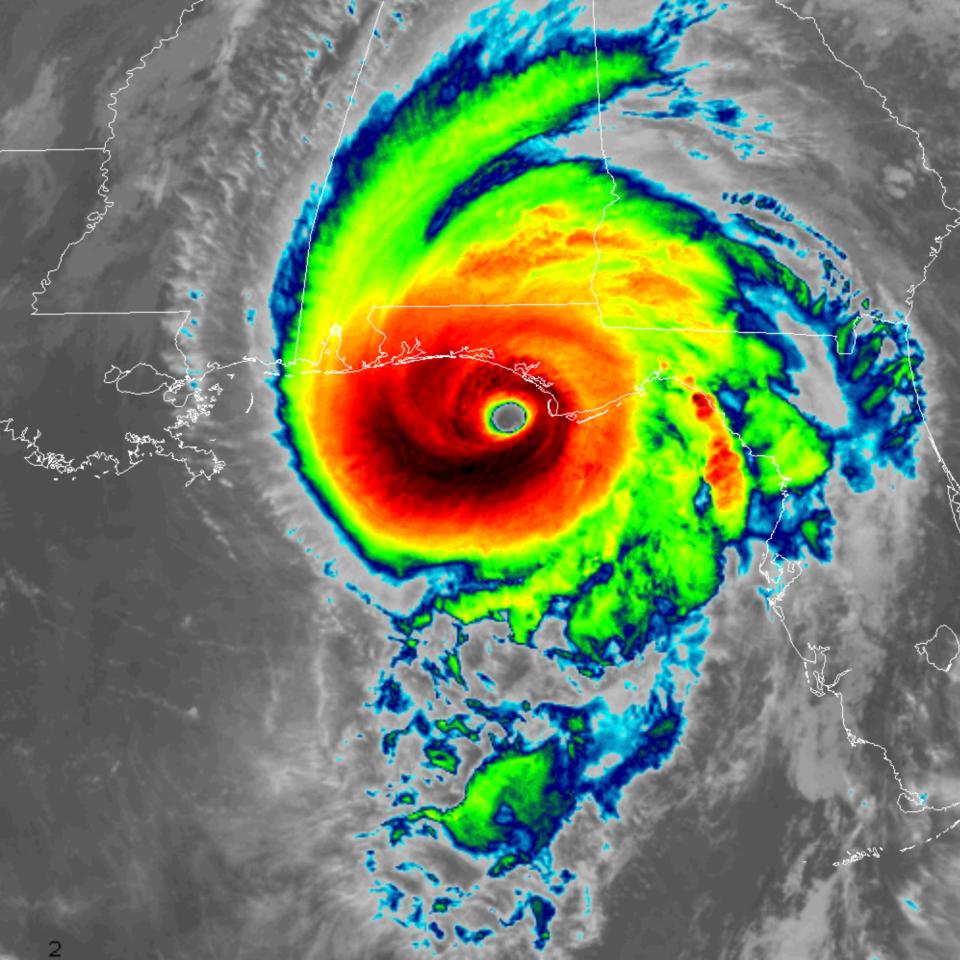

Michael had slammed into the coast between Tyndall Air Force Base and Mexico Beach as a Category 5 hurricane with sustained winds of 160 mph. Just 24 hours earlier, the hurricane’s sustained winds had been 110 mph, but the intensity exploded when warm waters and conditions in the Gulf of Mexico handed Michael the equivalent of a high-octane energy drink.

Such sudden spikes have been the hallmark of history’s most fearsome hurricanes, Ken Graham, director of the National Hurricane Center, told USA TODAY. Out of the nine hurricanes with winds of 150 mph or greater that struck the U.S. mainland over 103 years, all but one saw the explosion of force and power known as rapid intensification.

With the days ticking down to the start of this year’s Atlantic hurricane season on June 1, it’s worth noting that nearly half of those most powerful storms – Charley, Laura, Ida and Michael – made landfall in the U.S. just in the last 18 years. As rising global temperatures continue heating up the Gulf and other tropical waters, it’s a phenomenon some experts expect to see more often.

Given the rapidly morphing storms and the increased hurricane activity in recent years, Graham and others said it’s clear there’s a need for continued improvements to forecasting, evacuation preparation and ocean observation – and for residents in hurricane-prone areas to remain vigilant.

Already this year, water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are warmer than normal. And a rejuvenated La Nina current in the Pacific Ocean could mean more favorable conditions for hurricanes.

Last year’s season was the sixth in a row of above-normal hurricane activity, even after the 30-year normal was adjusted upward to 14 named storms rather than 12. Combined, the past two seasons produced 51 named storms and 21 hurricanes.

It’s the increased intensity in the strongest storms that most concerns forecasters. They’ve seen busy seasons before. But more Category 4 and Category 5 hurricanes slammed into the U.S. over the past five years than in the previous 54. "It's crazy," Graham said.

Five of last year’s storms experienced rapid intensification, including Grace and Ida, which strengthened right to the last minute, said Phil Klotzbach, research scientist and lead author of the seasonal Atlantic hurricane forecasts in Colorado State University's atmospheric science department. So did Laura and Zeta in 2020, when 10 storms underwent rapid intensification.

Warming sea surface temperatures aren’t the sole driver of rapid increases in intensity, but they do tend to load the dice toward extreme high-end storms, Klotzbach said during a recent tropical weather conference. Other factors such as a lack of wind shear, heavy moisture and the organization of the storm all have an influence.

In a study published five years ago, Kerry Emanuel, a meteorologist and climate scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, suggested rapid intensification would occur more frequently in the warmer climate. That trend might be showing up already, Emanuel said, but it will take years of data to be sure.

Better forecasts for hurricane intensity

Forecasters struggled for decades to improve intensity forecasts, in part, because so many factors can influence what happens in a storm. But thanks to significant strides in observations and modeling, they knew Michael had the potential to rapidly intensify.

Five days before Michael made landfall, the McKinneys, both musicians, had been out of town at a folk music festival when someone mentioned the storm in the Gulf of Mexico. For the 24 million people who live in counties that border the Gulf Coast that was cause to prepare but not necessarily to be alarmed.

When they returned home the next day, they started the familiar prep, checking their rain barrels, strapping a cover over the above-ground pool, and laying in supplies, including the Jameson.

By Tuesday, 24 hours before landfall, they were ready. They didn’t expect high winds to be a concern where they were. A friend’s kids didn’t want him to stay near Panama City Beach alone, so he drove up to stay with them.

But conditions in the Gulf were whipping up a recipe for disaster. Sea surface temperatures were 85 degrees. Vertical wind shear was decreasing. Hurricane center forecasters continued to warn that strengthening could occur until landfall.

Among the conditions that influenced Michael’s rapid intensification were the Gulf of Mexico loop current, a thick layer of warmer water that circulates into the Gulf from the Caribbean Sea. It also spins off eddies of warm water, said Matthieu Le Henaff, a physical oceanographer and associate scientist at the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies and the federal Atlantic Oceanographic Meteorological Laboratory.

The current and the westward-drifting eddies act as reservoirs for hurricane energy, Le Henaff said. Michael passed over the loop current and one of its warm eddies. It also passed over the plume of warm freshwater flowing out of the Mississippi River, he said. “During all those stages the intensity of the hurricane kept increasing.”

That makes observing and forecasting ocean conditions critically important, he said, and he’s encouraged by work underway by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to do just that.

Last summer, an autonomous ocean drone, called a Saildrone, launched in the Atlantic Ocean, captured video footage inside Hurricane Sam. It was part of an NOAA effort to better understand how the ocean’s interaction with storms affects intensification, by observing conditions such as water and air temperature, salinity, waves and air pressure.

This summer, the agency plans to pair surface Saildrones and underwater gliders for the second hurricane season in a row. By bringing the vehicles close to each other, the agency can capture measurements at the same place and time, painting a fuller picture of the dynamics that are known to influence hurricane strength, said Jennie Lyons, director of public affairs for NOAA’s National Ocean Service.

With so many storms undergoing rapid increases in intensity, Graham said it’s more important for people to know their risks and prepare earlier for evacuations.

“The perception of these big storms is you have lots of time. Five days, seven days, 10 days watching it across the Atlantic. That's not the case,” Graham said. People don’t always have time before they have to decide to do something, and that means you can’t wait until it’s too late.

Everyone in hurricane-prone areas should have a plan ready three days or less before a potential landfall, he said. That doesn’t mean they have to drive 100 miles. Sometimes people in storm surge zones and flood zones may need to drive only 5 to 10 miles to get away from the flood risk.

The McKinneys briefly considered leaving, but by the time they woke up Wednesday morning, she said the storm was too powerful to risk getting on the road. They knew they weren’t likely to flood. They had not expected such high winds and were more concerned about being stuck in traffic if they tried to flee.

Maggie does not regret staying home and would do it again, even though the 20 minutes they spent in the bathroom with their friend and pets – Zulu, the black Labrador retriever, and cats Nosmo and Cosmo – were intense.

Her husband, on the other hand, would never do it again, she said. “He said we would leave a month early.”

Dinah Voyles Pulver covers climate change and environmental issues for USA TODAY. You can contact her at dpulver@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 2022 hurricane season: Beware increase in rapidly intensifying storms