Hurricane season starts soon. Here’s the exclusive Max Defender 8 early outlook

Jeff Berardelli is WFLA’s Chief Meteorologist and Climate Specialist Jeff Berardelli

TAMPA, Fla. (WFLA) — Hurricane season is now only one month away. And all signs are pointing to, not just an active season, but a hyperactive season.

In fact, it is not an exaggeration to say that early season parameters we look at to forecast seasonal activity are as robust as we have ever seen.

From Alberto to William: Here’s the list of 2024 hurricane names

Let’s look at the factors driving our concern.

First and foremost, the best correlation we have to Atlantic hurricane season activity is Tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures. When the Atlantic is warm, generally there are more and stronger storms.

For the past few months, sea surface temperatures in the main development region of the Atlantic have been running above record levels. They still are right now. In fact, the temperatures from the Caribbean east to Africa are at levels we would expect in late July.

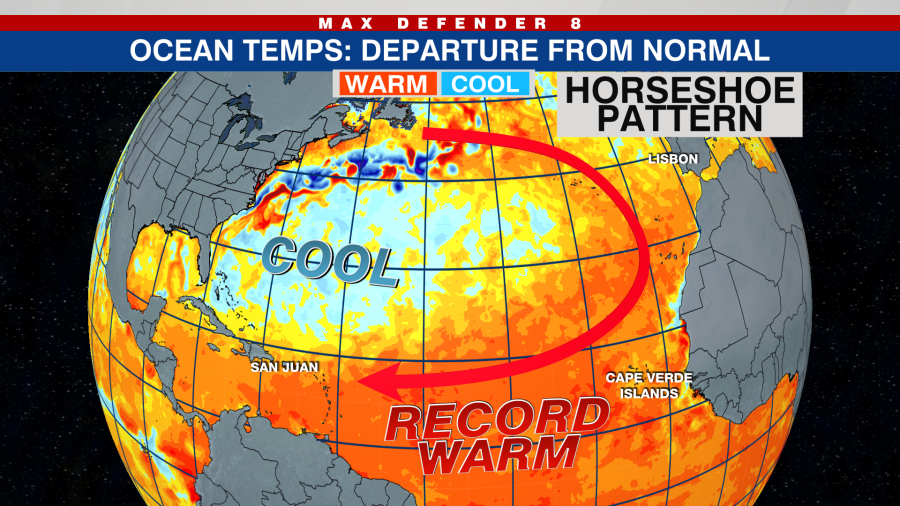

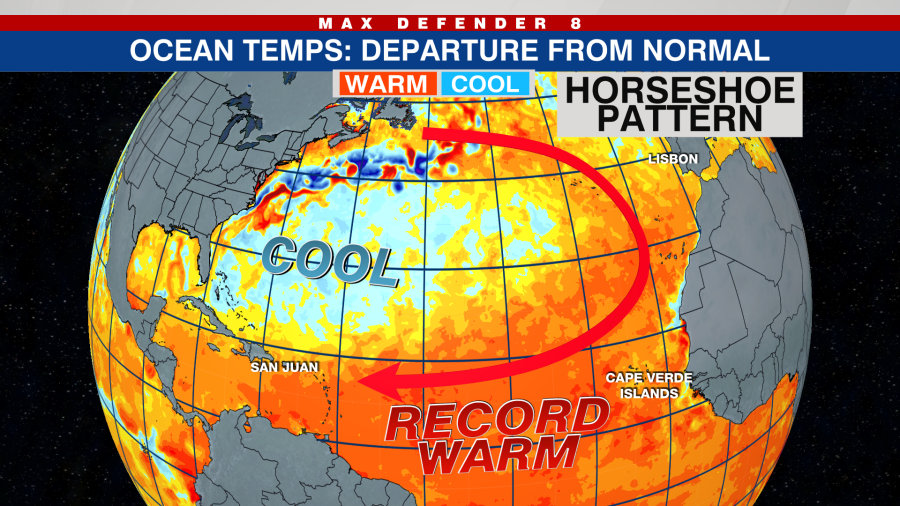

The pattern of sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic gives us a clue. This year they are arranged in a classic horseshoe pattern – this is well known to be associated with active Atlantic hurricane seasons.

Astronauts to launch from Cape Canaveral for its 1st human spaceflight in nearly 56 years

If you look at the graphic below you can see that the tropical regions are record warm, but the western Atlantic off the US Eastern Seaboard are cooler than normal. This is important because it means the tropical areas are concentrating heat and are warmer “relative to” the rest of the basin.

The word relative is important because oftentimes weather is regulated not by absolute warmth, but more so by relative warmth, ie. where it is relatively warmer than it should be.

Air trends rise over these relatively warm areas. This summer it appears that it will be over the main area where tropical systems form.

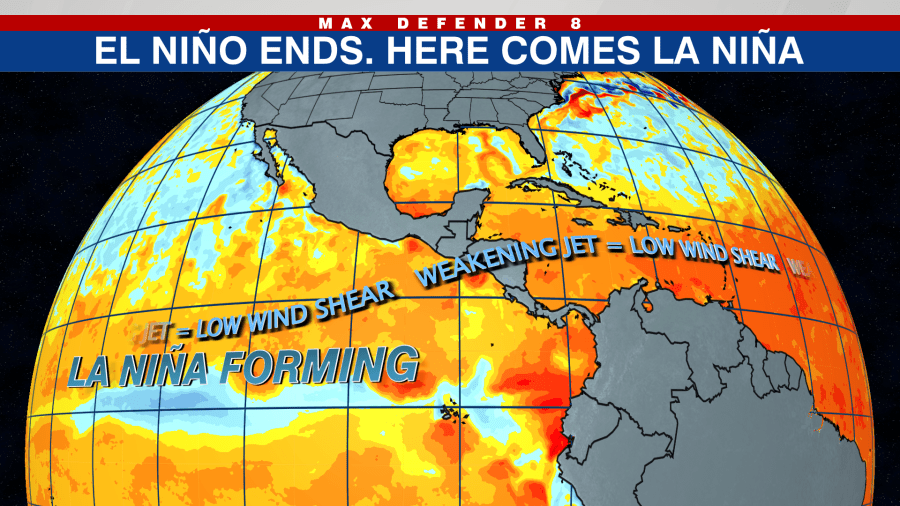

So the Atlantic is blinking red for development. But what about the Pacific Ocean’s influence on the Atlantic Basin, namely El Niño and La Niña? These oscillating phenomena have a big impact on hurricane season. La Niña’s tend to produce almost double the number of hurricanes and we are heading into a La Niña now.

Tampa, 2 other Florida cities among top 100 places to live, report says

You can see this in the following graphic. The sea surface around the Equator, which was bright red for warmer than normal this winter, has now turned blue, indicating cooler than normal water and the transition underway to La Niña.

Being that La Niña makes the tropical Pacific cooler it has two impacts. First, it is “relatively” cooler than the Atlantic, so air tends to rise (and form storms) over the relatively warmer basin, which is the Atlantic this season. Second, La Niña weakens the subtropical air flow and corresponding wind shear flowing into the Tropical Atlantic. This provides a less disturbed environment for storms to form and intensify.

Lastly, let’s talk about steering flow. Last spring the computer models forecast a steering flow that hinted at recurving storms during hurricane season – meaning most would recurve east of the U.S. and near Bermuda. Turns out they were correct.

This season the computer models are insistent that the storm track will point directly into the Caribbean. This is a more ominous sign for the Caribbean Islands, Central America and the U.S. mainland. This seems likely to be correct given the vast model agreement.

What we don’t know yet is how many of these storms will move north from the Caribbean and impact Florida or the Gulf Coast. That remains to be seen, but in La Niña summers, like it’s expected this season, Florida tends to be hit more often. As seen below, over the past 40 years, Florida hits – or near misses – are about 50% higher in La Niña summers.

So what does this mean in numbers for this upcoming season? Let’s start with the average or normal amount of systems. The 30-year average is 14 named storms. But the last five years have averaged 21 named storms.

Coast Guard pulls Carnival cruise crew member from ship off Florida coast

Last hurricane season – an El Niño season which should have been more quiet – the Atlantic had an impressive 20 storms. It seems likely we will see at least a few more this season. However, although 2023 had many named storms, it only had seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes, which is the 30-year normal. So El Niño was able to keep the storms weak, thus the seasonal energy (ACE) produced by these systems was only about 20% higher than normal.

This season, with no El Niño, we have a much more favorable pattern for storms to grow. Therefore we should see many more of those weaker systems strengthen to hurricanes and even major hurricanes.

This is not an official forecast, it is only meant to give a ballpark estimate. With that said, given the above evidence, it stands to reason that this season we should see named storms totaling in the middle 20s, 10+ hurricanes and at least five majors. What we can’t say is how many of these will hit the U.S.

Bottom line, given the stakes in the upcoming hurricane season, it would be prudent to start going over your hurricane plan and kit.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WFLA.