My Husband Became a Poster Child of the Post-Antibiotic Era

As an infectious disease epidemiologist, you’d think that I would have known that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a more immediate threat to global health than climate change. But it took a superbug that was resistant to all antibiotics to attack my husband, who nearly died after seven cases of septic shock and nine months of hospitalization, to give me the biggest wake-up call of my life.

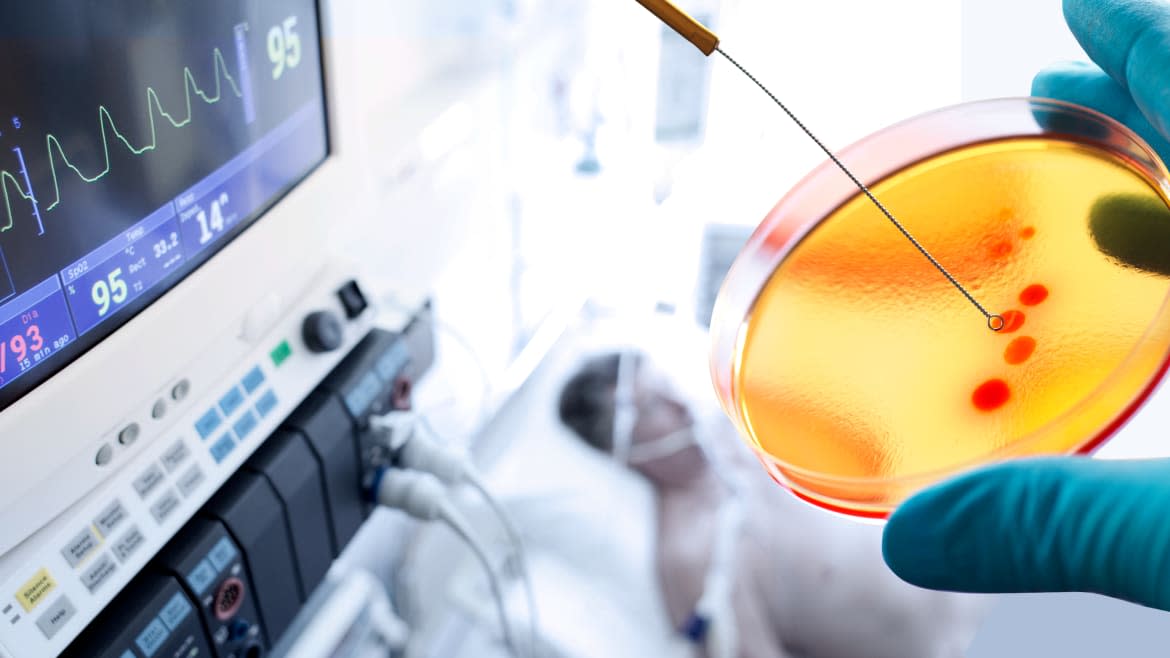

In November 2015, Tom and I were on a bucket list holiday in Egypt when he came down with what first resembled a stomach bug. Only it wasn’t. After being medevacked to a hospital in Germany, doctors discovered that a gallstone had lodged inside his bile duct causing an abscess the size of a football to grow inside his abdomen. Tom was delirious and semi-conscious in the ICU when the doctor entered, fully gowned and gloved, and showed us a flask filled with putrid brown fluid that had been sampled from Tom’s abscess. Gallstones were the least of Tom’s problems, he said. Something was growing inside the abscess; the lab was culturing it to find out.

Two days later, the doctor re-entered Tom’s room in the ICU, donning new gloves and a gown but also a face mask showing only his eyes. They were wide with alarm. “The abscess is infected with the worst bacteria on the planet”, he told us. Acinetobacter baumannii.

I vaguely recalled streaking A.baumannii on petri plates when I was in college back in the 1980s. It was considered relatively harmless then, not requiring any special handling other than a lab coat and gloves. Since then, it had earned the nickname ‘Iraqibacter’ because it had hitchhiked on the military’s evacuation system from the Middle East, infiltrating hospitals in Europe and the US along the way. Many vets survived their injuries, only to succumb to Iraqibacter. Over the last few decades, A.baumannii has become a bacterial kleptomaniac, adept at stealing antibiotic-resistance genes from other bacteria, earning the dubious distinction of being public enemy No. 1 on the World Health Organization’s list of the deadliest superbugs. Since its sticky ‘fingers’ cling to lab coats, hospital linens and medical equipment, A.baumannii is a medical menace, having been implicated in several outbreaks that closed down hospitals. To propagate itself, it has not only succeeded in manipulating the microbial world, but an entire health-care system. In Germany, any time it turns up, doctors are required to report it to the country’s health authorities.

Tom’s A.baumannii strain initially showed resistance to 15 antibiotics. While this was bad news, I had faith in modern medicine. Surely one of the three remaining antibiotics in the quiver of modern medicine would rescue Tom, right? Not so fast. One of these antibiotics was colistin. It wasn’t exactly a modern miracle drug, having been developed in World War II, and it was extremely toxic. Apart from its use in medicine, colistin was fed to livestock in many countries as a growth promoter. Feeding animals the same antibiotics that are used to treat people turned out to be a bad idea. Around the time Tom fell ill in Egypt, the first report of a gene conferring resistance to colistin was reported among pigs in China. In the blink of an eye, the colistin resistance gene had spread to 30 countries. And to Tom. By the time Tom arrived by air ambulance at our local hospital at UC San Diego, his A.baumannii isolate had acquired it, along with 50 other antibiotic resistance genes.

Unlike Germany, however, there were no reporting requirements for A.baumannii in California, nor were there in most U.S. states. The same was (and remains) true for other superbugs, with the exception of MRSA, which U.S. hospitals are now required to report. This means that for most superbugs, health departments and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) don’t track who acquires them, nor do they know how many recovered or died. The most recent CDC report estimates that 23,000 people die in the U.S. each year from superbug infections, based on data from 2010. But a recent report estimated that at least 153,000 people died from superbug infections the same year, an estimate that is nearly seven-fold higher. We are allowing most superbugs to maintain their invisibility under the radar, where they are spreading quietly. Unreported. Undetected. And, increasingly, untreatable.

The notion that we can beat the burgeoning superbug crisis with the existing antibiotic pipeline is a pipette dream. Antibiotics take at least a decade to develop. Seeing diminished returns on their investment, only four major pharmas continue to develop new ones.

Alternatives to antibiotics are desperately needed. I knew that first hand as I watched Tom being eaten from the inside out in the ICU, losing one hundred pounds from what had been a muscular frame. Antibiotics weren’t going to save Tom’s life, so I turned to the internet to conduct my own research. Buried in the scientific literature was a hundred-year-old forgotten cure that rang a bell from my college days: bacteriophages.

Bacteriophages (phages) are viruses that have naturally evolved to attack bacteria. They were first successfully used to treat children with dysentery during an outbreak in Paris in 1919, and in the following two decades were widely used. But after penicillin was introduced in 1942, phage therapy was largely abandoned in the West. It was embraced in what is now the former Soviet Union, but due to the lack of rigorous data from clinical trials, phage therapy is not yet licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration, which still considers it experimental.

Injecting billions of viruses into your husband to save him from his superbug infection might sound crazy, but Tom and I are scientists. And I knew he was dying. When I proposed phage therapy to the doctors treating Tom in early 2016, most of them had never heard of it. Most were skeptical, but were willing to give it a try. Together, we managed to find a global network of phage researchers who came to our rescue. Two research teams, one from Texas A&M and the other from the U.S. Navy Medical Research Center, embarked on a ‘phage hunt’ and each developed a phage cocktail personalized for Tom’s Iraqibacter, sourcing phage from their laboratories and environmental sources where bacteria are abundant, including sewage.

Within three weeks, my colleagues and I obtained emergency approval from the FDA to treat Tom with phage therapy on a compassionate basis. Within days after injecting phages into his bloodstream, he woke from a deep coma and began to recover. He’s now enjoying life and back at work.

Tom’s case also went viral in another way. After his case was presented and published, patients with superbug infections and their loved ones started contacting me and his doctors, from all over the world. We helped some, but others died before we could identify phages for them in time. In 2018, the UCSD chancellor provided my colleagues and me with seed funding to launch the nonprofit Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH). Our goal is to conduct clinical trials on phage therapy, while continuing to help people obtain experimental phage therapy if they have superbug infections that are no longer responding to antibiotics. So far, IPATH has treated seven patients at UCSD and over a dozen others in the US and internationally.

AMR is not just a problem in developing countries. Globally, the problem is getting worse due to over-use of antibiotics in livestock and in people. By 2050, it’s estimated that 10 million people, or one person every three seconds, will die from superbug infections unless urgent action is taken. The possibility of living in a post-antibiotic era where simple surgeries or scrapes could lead to an infection that requires limb amputation or results in death means we need to improve AMR surveillance, diagnosis and treatment. This includes antibiotics, but should also include phage therapy. We can’t afford to bury a promising alternative to antibiotics for another hundred years.

Steffanie Strathdee is the author of The Perfect Predator: A Scientist's Race to Save Her Husband from a Deadly Superbug.