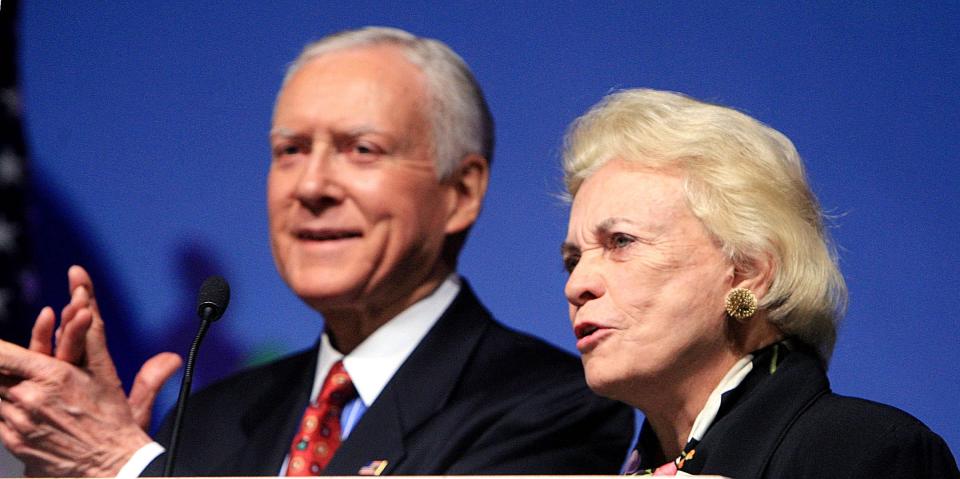

Iconic Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was more than a trailblazer, she was a dear friend and mentor to these Utah lawyers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As Utahns RonNell Andersen Jones and Denise Lindberg join the line on the steps of the Supreme Court Monday morning as the late Justice Sandra Day O’Connor is carried to the court’s Great Hall to lie in repose, you have to wonder what they will be thinking.

For them, it’s personal. Each served a term as O’Connor’s law clerk, and their professional relationships and friendships with the justice endured for decades after that.

“The country has lost an icon and a trailblazer, and I’ve lost a mentor and friend,” said Andersen Jones, who after clerking for O’Connor in the court’s 2003-2004 term, teamed with her to teach a course on the Constitution at the University of Arizona’s college of law.

O’Connor, the first woman appointed to the Supreme Court by then-President Ronald Reagan in 1981, died Dec. 1, of complications related to advanced dementia and a respiratory illness. She was 93 years old.

Andersen Jones said O’Connor had been in decline for an extended period, so her passing was not unexpected.

“But it still hit hard for those of us who were close to her. It’s frankly just difficult to imagine a world without her. I had the chance to visit her in Arizona several times between her announcement that she was withdrawing from public life and her passing. Even as she declined, she had such a powerful strength about her. I honestly have never known a stronger person in my life,” she said.

Following her clerkship in the Supreme Court’s 1990-1991 term, Lindberg practiced law with a couple of national firms in Washington, D.C., before being recruited as general counsel of a company in Salt Lake City. The position appealed to her because her family wanted to return to Utah.

“But when the company was sold, the first thing I did was fly back to D.C. and to talk to her and get her input. She was very pointed. She said, ‘What do you want to do?’ I said, ‘I’d like to be a judge. How do I prepare myself for that?’ She put me in touch with people who could tell me about that, could respond and help me,” she said.

In 1998, then-Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt appointed Lindberg to the 3rd District Court bench. She served until her retirement in 2014, but she has retained senior judge status. She also served on the Young Women’s General Board of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and has worked in various capacities with the International Center for Law and Religion Studies.

Lindberg said her relationship with O’Connor evolved over time. Early in her clerkship, O’Connor was “pretty formal. I always assumed it was because she had come up during a time when women were so rare in the profession. They just had to be very circumspect in how they acted.”

That changed as the term progressed and O’Connor got to know her clerks’ strengths and weaknesses, Lindberg said. The relationships moved to another level once Lindberg and her co-clerks completed their service.

“She was a very different, much warmer person. She always made a point of asking about our children, what they were up to. ... It was different because I was closer in age to her than I was to my co-clerks. She became very interested in helping advance my career, putting me in touch with people who could be of help. Once you became part of her clerk family, it was a very different relationship,” she said.

Lindberg and Andersen Jones each described their terms as Supreme Court clerks as highly demanding.

“Most of my co-clerks worked seven days a week. I told Justice O’Connor that I would prefer to not work on Sunday and she said, ‘I don’t care as long as you get your work done, and you’re not a burden on your co-clerks.’ So I worked much longer days than my co-clerks, but I didn’t work on Sunday,” said Lindberg, whose children were in high school at the time.

Andersen Jones said her clerkship “was both the hardest and the most rewarding professional experience of my life. The justice took seriously the job that we did on behalf of the country, so the hours were long and the work was often difficult. But she also cared deeply about her clerks as people and urged us to follow her example of living a balanced, engaged life.”

Both recalled O’Connor loading her clerks into her car so they could take in the beauty of D.C.’s famed cherry blossoms in full bloom, visit exhibits at the Smithsonian not yet open to the public, or raft the Potomac River.

“She took me fly-fishing and hosted a pig-themed birthday party for my son in the courtyard outside her office. She was just constantly on the move and always hoping you’d be game for keeping up with her,” said Andersen Jones.

O’Connor and Andersen Jones both had rural roots, the justice raised on a cattle ranch in the high desert on the Arizona-New Mexico border. Andersen Jones’ father was also a rancher, who raised cattle and hogs in Tremonton.

Andersen Jones said she long thought that O’Connor’s jurisprudence reflected her Western upbringing.

“As someone who grew up in rural northern Utah, I absolutely recognized the cadence of her voice as she was working through issues. It was the same sort of brass-tacks analysis I’d often heard from farmers and ranchers in my hometown. She was a pragmatist — immensely concerned with making sure that the court’s solutions actually worked and incredibly interested in the impact that the rulings would have on real people,” Andersen Jones said.

Lindberg and Andersen Jones said O’Connor had intense interest in their legal careers and their families.

Andersen Jones taught at the University of Arizona and Brigham Young University law schools before joining the faculty at the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law, where she is a university distinguished professor and the Lee E. Teitelbaum Chair in Law.

She is a nationally recognized expert on the intersection of First Amendment law and the courts, and is currently a visiting research fellow at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University.

Andersen Jones said she especially cherished the opportunity to team teach with O’Connor at the University of Arizona’s law school.

“In the early years of the course, she was still on the bench, and so we taught it as a condensed course over the court’s February recess. After she retired, she continued to come to visit and teach the class. It was a total treat for my students and for me,” she said.

Andersen Jones has multiple cellphone photos of the justice with her children Scout and Max at varying events catching up what was going on in their lives and what books they happened to be reading at the time.

Over the years, the O’Connors were guests in the Lindbergs’ home in Utah, and they visited the O’Connors in Arizona, where they lived after she retired from the high court in 2006 to care for her husband, John, who had Alzheimer’s disease.

On a couple of her Utah trips, O’Connor met socially with groups of women judges in Utah.

O’Connor’s retirement from the Supreme Court after more than 24 years of service was painful for her, Lindberg said.

“I know how hard it was for her to give up the bench. We talked about that. She knew that he (John) needed her. She was worried that if she wanted to do something, it was going to be done right. She didn’t want to do what she felt would be a half-hearted job because she was divided by paying attention to her husband. So yeah, that was painful for her. That was difficult,” she said.

In retirement, O’Connor labored to improve civics education and on occasion sat with the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

“She spoke often about judicial independence and the rule of law, which are things that are very much being challenged these days. So, I mean, she found ways to continue contributing to the field, to the law when she could not do it as a justice. But that was still painful,” Lindberg said.

Andersen Jones said when O’Connor exited public life, “she bravely made public her dementia diagnosis and made clear the kind of work she hoped we all would continue in her name, especially efforts to advance civic education.

“She was in many respects a real prophetess on that issue — warning about the fragility of democracy and the urgent need for the people of the nation to understand government and show commitment to the rule of law,” she said.

As is tradition when a Supreme Court justice dies, groups of court clerks stand vigil while the justice lies in repose. Andersen Jones and Lindberg will participate in that observance and then attend O’Connor’s funeral service at Washington National Cathedral on Tuesday.