Idaho man’s hand broke, healed with ‘deformity’ in prison. It took months to see a surgeon

Bobby Templin used to spend 12 hours a day — 60 hours a week — working as a heavy equipment operator and pipe fitter. The 32-year-old started working in construction in 2008 and said he likes the work, particularly the “physically demanding” aspects. It was his last job before he ended up at the Idaho State Correctional Center in Kuna.

Templin at least expected to have his job waiting for him at MDM Construction Group in North Idaho after he got out of prison. He was hopeful that he’d get released early on parole and be back to work in a few months. But he’ll likely need to find another line of work now. Several months’ worth of delays for medical care for a fractured hand has left him with “a deformity,” according to his doctor.

Templin and the Idaho Department of Correction have very different stories of how Templin’s right thumb broke. Templin said it happened when correctional officers were restraining him after a fight broke out. An IDOC report said he punched a wall.

What was clear, through records obtained by the Idaho Statesman, is that it took IDOC six months to bring Templin to a surgeon, despite continual pleas from Templin for help. By then, an expert said, permanent damage was likely done.

“My hand hurts every day,” Templin told the Statesman in a phone interview from the Idaho Maximum Security Institution, where he now resides. “If they would have gotten me to the hospital like they’re supposed to … everything would be fine.”

Gang fight begins at IDOC facility

At around 5:30 p.m. Sunday, Jan. 29, a gang fight broke out in a housing unit at the Idaho State Correctional Center, according to disciplinary offense reports obtained by the Statesman through Templin’s family. Templin told the Statesman he was involved in the altercation, which escalated into a roughly 20-person fight.

Correctional officers told the group to stop fighting, according to an IDOC disciplinary report, and when the fight didn’t stop, the officers used “physical control” and “chemical munitions.” Authorities alleged that Templin struck an officer and resisted once he was on the ground. Templin denied hitting any guards. Patrick Orr, spokesperson for the Ada County Sheriff’s Office, told the Statesman by email that “the events of that day are still under investigation.”

After the guards handcuffed Templin and escorted him away from the fight, Templin told the Statesman, two guards started dragging him backward down the hallway and placed him in a wristlock. Templin said that’s when he felt his hand snap.

Prison officials denied Templin’s narrative. IDOC spokesperson Jeff Ray by email said an incident report described Templin punching a door and wall in his cell and in the showers after the fight. The Statesman submitted a public records request to review the incident report over a month ago but has yet to receive the record. IDOC also denied the Statesman’s request to interview Templin in person at the prison.

Templin filed a complaint with the department alleging that a guard broke his hand. In an April response in an offender grievance report, IDOC officers said that wasn’t possible, and that Templin was seen punching the wall.

“I never once punched the wall,” Templin told the Statesman.

Templin was moved into solitary confinement the same day, according to housing records. It wasn’t until a few days after the fight that Templin’s hand was examined, and officials determined that his right thumb was broken, Templin said. He was told that same week by a member of the medical staff that he’d be taken into surgery within the week, he said. That never happened.

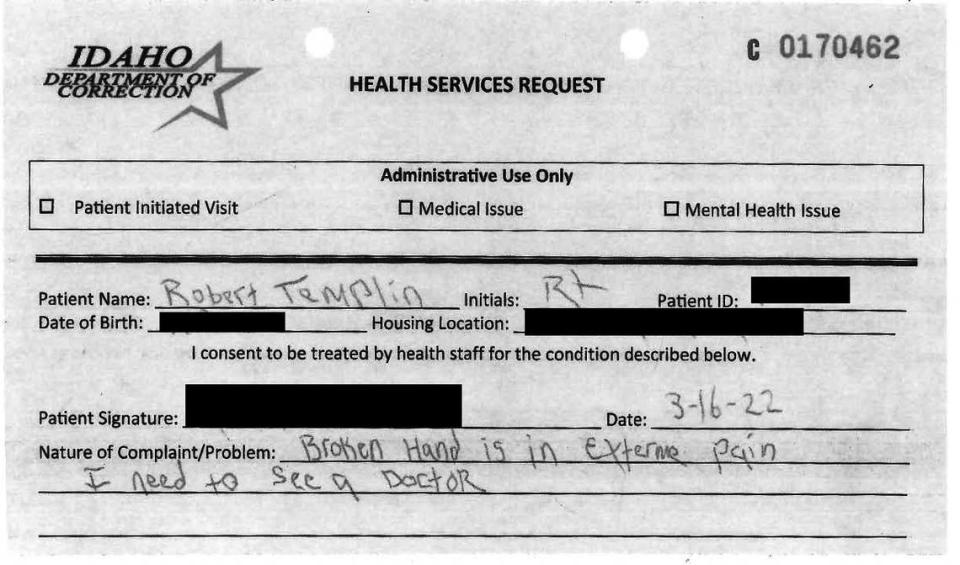

In non-emergent situations, individuals incarcerated within IDOC can request medical assistance through request forms. As each day passed without proper medical care, Templin sat — isolated and in pain, he said — in his cell and submitted health service requests in an attempt to see a doctor. Templin’s family provided copies of the service requests to the Statesman.

“My hand is in significant pain. My condition is worsening daily,” Templin wrote in one of at least two dozen health service requests submitted from February through May, which cost him $3 each to submit. “I’m scared my hand is sustaining irreversible damage.”

Templin also filled out dozens of resident concern forms, over the course of months. In response, employees from Centurion Health, the correctional department’s private medical provider, told him at least five times that he’d already been scheduled to see a surgeon, the forms provided to the Statesman showed.

“An off-site appointment has been scheduled,” an employee wrote on Feb. 27.

Roughly two weeks later, the employee told Templin: “You have an appointment scheduled, though we’re attempting to find an appointment sooner,” according to a concern form obtained by the Statesman.

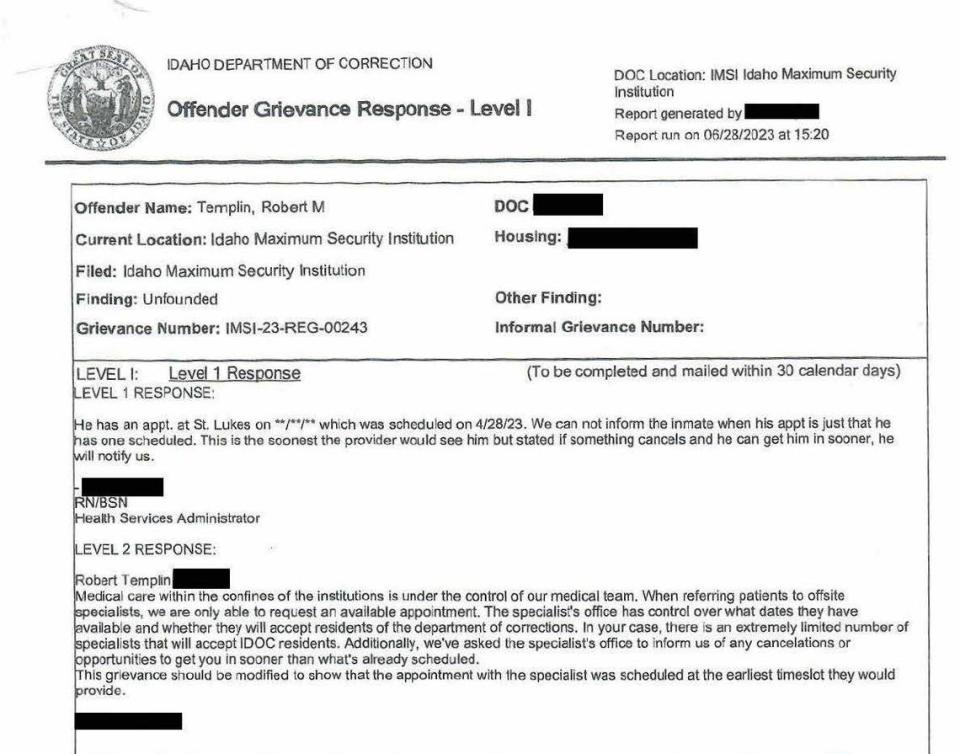

In fact, officials didn’t schedule his off-site doctor’s appointment until April 28, according to a response that was written by Centurion Health employees. They scheduled the appointment for July, six months after his hand broke.

The Statesman also requested Templin’s complete medical records in the prison but was denied them, despite Templin signing a release of medical information. IDOC, in its denial, said medical records can only be released to Templin’s attorney, medical provider or an “eligible discharged resident” of the department.

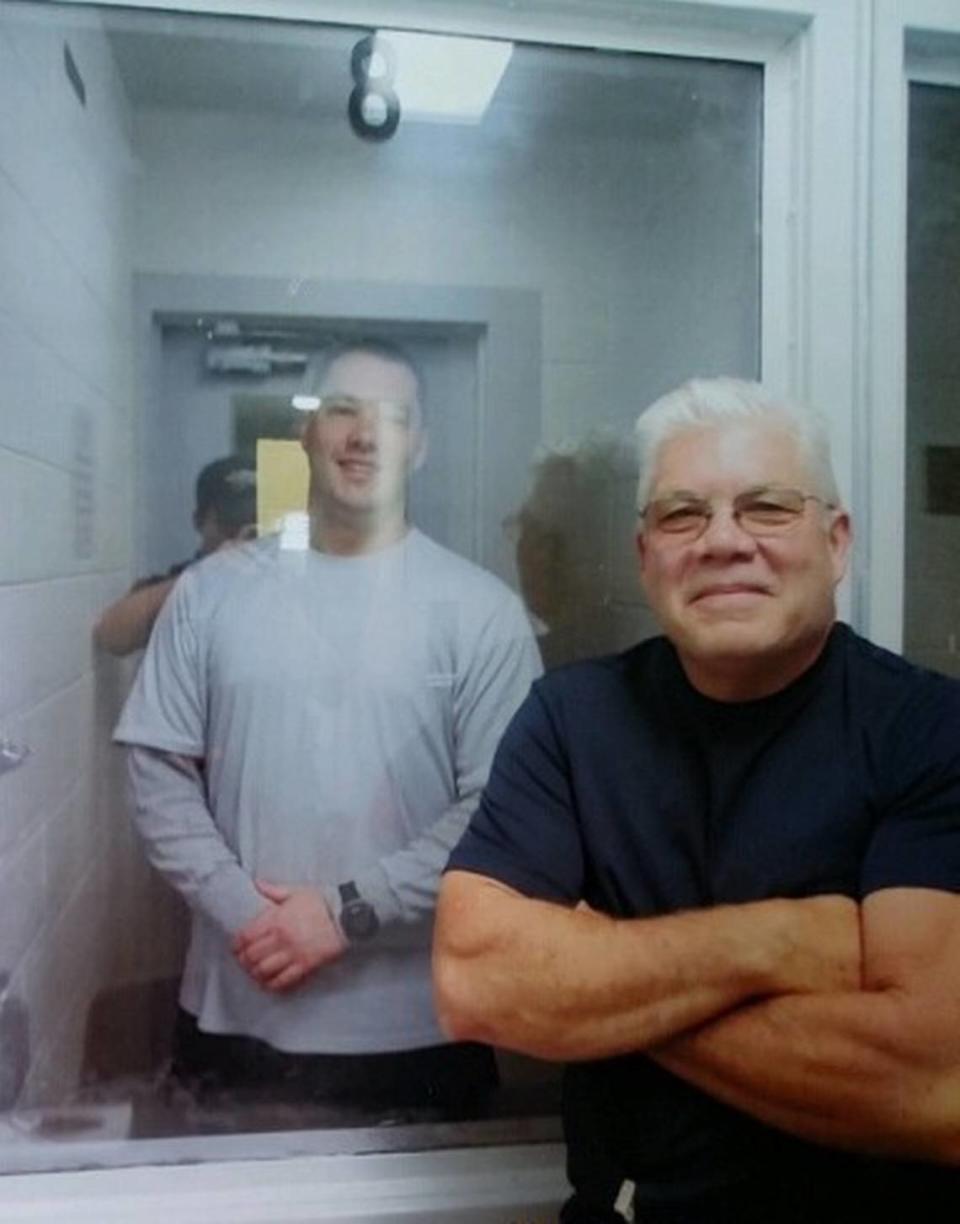

Bob Templin has been advocating for his son from outside the prison since he was injured. He has contacted prison officials, politicians and the Idaho Commission of Pardons and Parole asking for Templin’s release so that he could address his medical and mental health issues. Templin is incarcerated on a possession of controlled substance charge.

“I turned him in. He was on heroin and I told him I wouldn’t put up with it,” Bob Templin told the Statesman by phone. “I’m kind of sorry now that I ever turned him in, but, you know, I’m a law-abiding citizen, and I just wasn’t going to put up with it. I thought that he would get some help.”

‘Limited number’ of specialists accept IDOC patients

The Idaho correctional department’s health care system has been privatized for over 20 years. In 2021, IDOC entered into a five-year, $299.4 million contract with Centurion Health after it rejected renewing its 10-year-plus contract with Corizon Health for another year. At least two dozen other correctional agencies allowed their contracts with Corizon Health to expire from 2016 to 2021, the Marshall Project reported.

Corizon Health by that time faced years of allegations of medical negligence nationwide. In Idaho, a man in 2017 sued Corizon Health and said he swallowed a razor blade so staff would take him to the hospital to treat a flesh-eating infection in his leg. The case was eventually dismissed. In 2018, St. Luke’s and Saint Alphonsus health systems also sued Corizon Health, alleging it paid them Medicaid rates, which were “substantially lower” than the initial agreed upon rates, according to previous Statesman reporting. The lawsuit was paused, pending the approval of a settlement.

Still, despite IDOC’s switch to a new company, coordination among IDOC, a privatized company and health care providers was a major factor in Templin’s delayed care, according to the records obtained by the Statesman. In one of Templin’s grievances, he asked why he still hadn’t seen an orthopedic surgeon. Centurion Health employees in a June response told Templin the delay was because of outside health care providers.

A health services administrator employed by Centurion Health had told Templin that there is an “extremely limited number of specialists that will accept IDOC residents,” according to the June offender grievance response.

A St. Luke’s health system spokesperson, Christine Myron, told the Statesman by email that incarcerated patients are “treated the same as any other patients” and that they are seen, evaluated and stabilized with the “same urgency and compassion as any patient who comes to St. Luke’s for care.” Saint Al’s declined to comment, citing pending litigation.

Bobby Templin said he also tried asking the correctional officers for help but that they’d tell him they don’t work for the medical provider, which is a separate entity from IDOC.

“It was really hard to get any medical help,” Templin said. “I’d have to ask, ask, ask, ask.”

Ray, the spokesperson for IDOC, said any questions regarding Templin’s medical care must be sent to Centurion Health — which didn’t respond to several phone calls, emails and a detailed list of questions sent by the Statesman and IDOC.

Templin’s hand ‘healed with a deformity’

On July 25, Templin was taken to St. Luke’s Clinic in Meridian and had his hand examined by Dr. Dustin Judd, an orthopedic surgeon, according to medical records provided to the Statesman. There, Judd determined Templin had a right thumb metacarpal intra-articular base fracture, also known as a Bennett or Rolando fracture, which had “healed with a deformity,” the records said.

Dr. Jerry Huang, a Seattle-based orthopedic surgeon, told the Statesman in a phone interview that Rolando and Bennett fractures are “almost always operative.”

Huang, a professor at the University of Washington’s Department of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine, who specializes in hand, wrist and elbow surgery, said the only exception would be cases in which the bone isn’t displaced. He said he’d recommend surgery for anything that is displaced by at least 1 millimeter. Templin’s fracture was displaced by 1.5 millimeters, medical records showed. Huang said such a gap in a joint can put someone at a “much higher” risk for arthritis.

Huang added that if an intra-articular base fracture doesn’t heal properly, it could lead to a gross deformity, stiffness, limited range of motion, weakness and “persistent pain that may never go away.”

Judd, according to the medical records, warned Templin about the possibility of developing “ongoing osteoarthritis” in his thumb, which “can be painful.” Osteoarthritis is a common type of arthritis in which the cartilage in the joints breaks down.

Myron, the St. Luke’s spokesperson, said that in the past few years, four hand surgeons have left the hospital system, leaving a single surgeon to oversee the patient load. The shortage has impacted both hand-related clinic appointments and surgery wait times, Myron said, adding that the typical wait time for elective hand surgery is four to six months, though emergency cases get priority. St. Luke’s will be hiring a new hand surgeon next month, Myron said.

Templin’s doctor suggested he wait it out and see if the pain in his thumb subsides, according to the medical records. Templin told the Statesman his thumb is constantly swelling again and hurts at the base, where it connects to his wrist, up through the finger.

If the pain doesn’t lessen, medical records show Judd is considering two surgical options: a CMC fusion or a CMC arthroplasty. A fusion would fuse the joints together and can offer stability and pain relief, though it would limit a patient’s mobility, while an arthroplasty uses the patient’s tendon to replace the joint. When asked in general about fractures like Templin’s, Huang said an arthroplasty wouldn’t fully heal the injury, and that the joint would loosen over time.

Meanwhile, Templin said he’s still in pain. He said he had put his faith in the system, but that the system is clearly broken.

“If I was on the streets, I would have access to certain things that I wasn’t granted in here,” Templin said.

Templin isolated after fight

For Templin, daily tasks are still difficult. He told the Statesman that he has “limited hand function.” Washing his clothes or exercising, he said, is challenging.

Templin is still taking Tylenol several times a day, he said, and was taking Voltaren, an anti-inflammatory drug that can treat pain and arthritis, up until recently. Templin said the prison’s pharmacy provider changed so he’s now being prescribed Meloxicam, another anti-inflammatory medication, but it doesn’t work as well, and he’s experiencing increased pain in his hand.

The pain hasn’t just been physical for Templin. He said he began experiencing anxiety and depression after he was placed in solitary confinement the day his hand was broken. He’s also been prescribed Celexa, which is an anti-depressant.

“I’m in here by myself all day, every day. It was really tormenting when my hand proceeded to hurt all day, because all I want to do is make it better … and I felt like I wasn’t being heard,” Templin said. “That was the most frustrating thing, is I’d see people through my cell window that could help me, but they just pass by.”

Ray said IDOC doesn’t use solitary confinement and calls it “restrictive housing,” because inmates have “frequent contact with staff.” The U.S. Department of Justice uses the terms interchangeably. Templin said he’s being housed in isolation 23-24 hours a day.

Templin in March was transferred to Idaho Maximum Security Institution’s administrative segregation, which is a classification within restrictive housing and is for individuals who “pose a threat to life, property, self, staff” or whose presence threatens the security of the prison, according to the department’s standard operating procedure. It’s the same housing status for people awaiting death row.

Templin’s classification status — which determines where someone is held — was changed after the fight in January. Prison officials said he was found guilty of violating two internal rules: violence against staff and involvement in a group disruption. His confinement status will be up for review on Nov. 11. He’s been in solitary confinement for more than eight months.

Templin asked to be released from prison early on medical leave, but he said that request was denied. Templin’s request to be released on parole was also denied, keeping him in prison until 2025, according to hearing minutes obtained by the Statesman through a public records request. He’s supposed to return to the hospital in three months, but he said the prison hasn’t scheduled an appointment yet.

About solitary confinement

Bobby Templin has been in solitary confinement since his hand was broken, and the nearly nine months he’s spent isolated have caused his mental health to deteriorate. An expert told the Statesman plenty of research supports his claim.

Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, an associate professor at Duke University who researches the health impact of incarceration, told the Statesman in a phone interview that incarcerated people feel their well-being decline even without staying in isolation long term. She also pointed out that the United Nations considers solitary confinement a form of torture.

“There is a giant body of literature that shows any amount of time spent in solitary confinement can have a deeply negative effect on people’s mental and physical health,” Brinkley-Rubinstein said.

Brinkley-Rubinstein said the U.S. still sees an “overuse of solitary confinement,” but some prison systems like New Jersey and Colorado have placed restrictions on how long an individual can be isolated. Though the United Nations opposes the overall use of solitary confinement, if prisons and jails do plan to use it, the UN said solitary confinement shouldn’t exceed 15 days.