Idaho ‘serial killer’ Thomas Creech’s death sentence upheld after rare clemency review

Thomas Creech will remain Idaho’s longest-serving death row prisoner after the state parole board recommended Monday against his plea to avoid execution with a reduced sentence to life in prison.

Creech was convicted of five murders, including the beating death of fellow prisoner David Dale Jensen in 1981. He is suspected of at least several others across the Western U.S. but asked that he be allowed to die of natural causes at a formal hearing earlier this month.

The Commission of Pardons and Parole deadlocked in a 3-3 vote, which upholds Creech’s death sentence because a majority did not support his request. The parole board’s seventh member, a retired longtime Idaho State Police officer, recused himself from the clemency hearing for undisclosed reasons.

“We do not believe Mr. Creech is worthy of grace or mercy,” the three unnamed parole board members said in the ruling. “This decision was based on the coldblooded nature of David Dale Jensen’s murder and the sheer number of victims that Mr. Creech has created over his lifetime, which shows that he does not place value on human life, other than his own.”

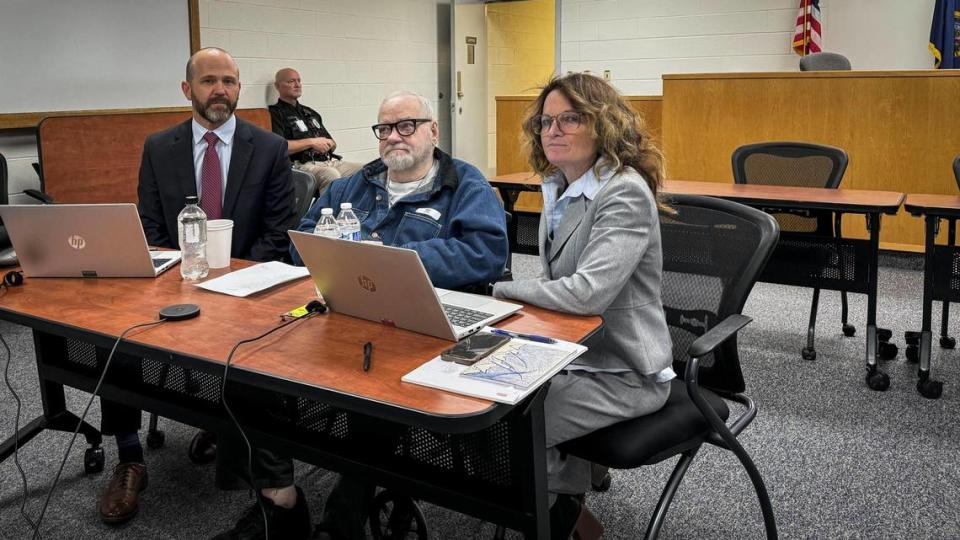

Creech’s attorneys with the nonprofit Federal Defender Services of Idaho said in a Monday evening statement that they were grateful to the three parole board members who “chose grace over vengeance” and vowed to fight on for their client.

“We believe the split vote clearly reflects the undeniable fact that Tom has made a remarkable turnaround during his 50 years in prison, becoming a deeply remorseful, compassionate and harmless old man who has wide support for clemency across the prison ranks and even from the judge who sentenced him,” Deborah A. Czuba, supervising attorney for the legal nonprofit’s death penalty unit, said in the statement. “We are hopeful that the governor will still find a way to favor life and grant clemency. Either way, our fight is far from over and we will continue to do everything we can to spare Tom an execution.”

Gov. Brad Little, who has the final say on clemency decisions, said in a statement that part of his job is to follow the law and ensure criminal sentences are carried out as ordered.

“Thomas Creech is a convicted serial killer responsible for acts of extreme violence,” Little said. “As governor, I have zero intention of taking any action that would halt or delay Creech’s execution. His lawful and just sentence must be carried out as ordered by the court. Justice has been delayed long enough.”

A broad group of advocates backed Creech’s push to drop his death sentence to life in prison after having been incarcerated for nearly a half-century. His supporters included several former state prison workers, one current corrections officer who spoke at his clemency hearing, a former state lawmaker and the Ada County judge who gave Creech the death penalty.

”For me, Tom has become a living symbol for the problems with the death penalty,” former state Rep. Donna Boe, who served from 1996 to 2010, wrote in Creech’s clemency petition. “I have no doubt that he has changed and grown as a person, that he has true care and concern for others including the staff who work at the prison, and that an execution would be a tragic waste of life.”

Creech, 73, has been convicted of five murders, including three in Idaho. He received his standing death sentence after he pleaded guilty to Jensen’s May 1981 murder. Creech previously said the incident was an act of self-defense, but still apologized for Jensen’s death at his hearing.

“I’m sorry with all my heart and soul,” Creech told the parole board. “If I could bring him back and trades places, I would do that.”

Creech, then 30, beat Jensen, a 23-year-old Pocatello man who was partially disabled before entering prison, using a sock filled with batteries. When the weapon broke, Creech kicked and stomped Jensen’s throat and head against his cell’s concrete floor and bed frame, prosecutors said.

“This is not self-defense. This is part of the lie Creech has been trying to tell you,” Ada County Deputy Prosecutor Jill Longhurst said at Creech’s clemency hearing.

Following release of the parole board’s decision Monday evening, the Ada County Prosecutor’s Office thanked the survivors of Creech’s victims, including Jensen’s family who attended the clemency hearing, for their willingness to relive the pain of losing their loved ones as part of the legal process.

“In 1981, the state sought the death penalty against Mr. Creech for the first-degree murder of Mr. Jensen,” the statement from the Prosecutor’s Office read. “Seeking the death penalty is not an easy decision or process. We continue to stand by the decision to seek the death penalty in this case.”

Jensen’s sister, two nieces and his daughter read victims’ statements at the hearing. Only one of them offered her first name, and the Prosecutor’s Office cited the victims’ rights clause of the Idaho Constitution to the Idaho Statesman for declining to identify Jensen’s family members.

Jensen’s daughter said she was 4 years old when Creech killed her father, and has dealt with decades of torment since his death.

“Execution is not an act of evil,” she said, “it’s the result of actions and choices.”

Creech’s past convictions and suspected murders

The three parole board members who voted against Creech’s request for a reduced sentence said in their decision that they did not believe he was “capable of true remorse.”

“The commission believes that the Jensen family would not receive justice if Mr. Creech received clemency and above all else that they deserve closure in this case,” they wrote. “If the commission cannot uphold the death penalty in this case, then the death penalty means nothing in the state of Idaho.”

Just months before killing Jensen, Creech used a razor blade mounted to a toothbrush — similar to a weapon Creech said Jensen tried to attack him with — to slash a different prisoner in the neck, arm and abdomen, Longhurst said. The Prosecutor’s Office declined to charge Creech for that assault, she said.

Creech was initially convicted in Idaho for the November 1974 double-murder of Edward Thomas Arnold, 34, and John Wayne Bradford, 40, in Valley County. He received the death penalty but had his sentence reduced to life in prison when the U.S. Supreme Court later ruled that death sentences may not be mandatory for a crime, as Idaho had in place at the time.

Creech was later convicted of a murder each in Oregon and California. Creech claimed at times, including under oath, to having killed as many as 42 people. He later revised the total to 26 murders he committed or at least participated in.

“I think everybody would have chose to live,” Creech said at his hearing earlier this month. “That’s why I feel so bad — they could have grown up to be anything.”

Longhurst detailed during her presentations before the parole board that Creech was responsible for at least 11 murders. That includes the October 1973 stabbing death of a 70-year-old man in Arizona — for which Creech was acquitted by a jury — and the October 1974 shooting of Daniel A. Walker Jr., 21, in San Bernardino County, California, that has gone unsolved for nearly 50 years and the prosecution linked to Creech for the first time at the hearing.

The San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Office announced in a press release last week that it resumed the investigation into Walker’s death in November after it “obtained additional information” but did not identify the source or what that information was. On Monday, the Ada County Prosecutor’s Office said one of its investigators was “instrumental” in relaying evidence to the Sheriff’s Office in Southern California that led to the naming of Creech as the suspect in the Walker murder.

Creech’s attorneys with the Federal Defender Services called the allegations brought by prosecutors against their client for the San Bernardino cold case “troubling” and “irresponsible,” especially given the lack of “any real evidence” presented at the clemency hearing.

“We are confident the parole commission will see through the prosecutors’ ruse and judge Mr. Creech based on the man he is in 2024, whose execution would accomplish nothing but more death and devastation,” Czuba said in a statement last week.

First Idaho death row clemency case denied by parole board

Robert Dunham, a Philadelphia-based lawyer who specializes in death penalty policies, questioned the constitutionality of prosecutors presenting either case at Creech’s clemency review, which he said is not designed to be a hearing to consider new evidence.

“I think they’re both problematic, and it’s one thing to allege that there are more crimes out there that have never gone to trial,” Dunham told the Statesman in a phone interview. “It’s another thing to say you should punish this person more harshly because he went to trial and he won.”

With increased frequency, prison workers advocate on behalf of death row prisoners across the U.S. in requests for clemency, he said. The impact of executions on guards and other staffers who develop relationships with prisoners after decades on death row is a “significant consideration,” even if reduced sentences for death row prisoners are still rarely granted, Dunham said.

Creech’s clemency hearing was just the third held in Idaho for a death row prisoner since capital punishment was reestablished in the state after a 1976 U.S. Supreme Court decision. In both prior reviews, the parole board voted to grant a reduced sentence to life in prison. Little blocked the most recent recommendation against a prisoner’s execution in December 2021.

Creech still has a handful of outstanding legal appeals over his death sentence, including two that are scheduled to go before the Idaho Supreme Court for oral arguments next week.

One appeal argues that Creech’s death sentence is unconstitutional because a judge imposed it rather than a jury, which the U.S. Supreme Court amended through case precedent in 2002. The other appeal argues that Creech had ineffective legal counsel during his prosecution for the Jensen murder, because Creech’s history of childhood physical and sexual abuse and traumatic head injuries were not presented to the judge for consideration at sentencing.

After meeting Creech in person at the maximum security prison some years back, retired Bishop Robert T. Hoshibata of the United Methodist Church advocated for sparing the prisoner’s life in recorded videos played at the clemency hearing. He told the Statesman by phone Monday night that he felt “sadness and despair” over the parole board’s denial of Creech’s plea.

“We all need to take a wider view of the sanctity of life, and that human judgment is not always what I think God would ask us to use in a case such as this,” Hoshibata said. “I can get my head around life without parole, but I cannot get my head and heart around the death penalty. For the person who is incarcerated, that just does not make sense to me.”