Illegal abortions shaped these Tennessee doctors' careers: 'Pre-Roe v. Wade was not easy'

More than 50 years later, Dr. Frank Boehm still remembers the desperate faces.

The mother in Wichita, Kansas, when Boehm confirmed her teenager’s pregnancy. Unmarried teen motherhood shamed the family. A week later, the mother brought her daughter back, bleeding from an incomplete abortion.

The Navy wives in Maryland, pregnant while their husbands were in Vietnam, and not with the husbands' babies.

Newly postpartum teenage girls from Nashville, Tennessee’s Florence Crittenden House for unwed mothers, sobbing. When he came for prenatal visits, they baked him cookies. When they gave birth, unconscious, he handed their babies to adoption coordinators without the young mothers ever holding them.

And a face beyond desperation: a Connecticut college student, comatose. She was dying of sepsis, a wire rod stuck so deep inside her it pierced her lung. Her parents’ faces were not desperate, but stunned. Even after his shift ended, Boehm sat and held her limp hand.

“It was a very traumatic experience for me,” Boehm said. “This was something that had to change in America. We couldn’t let women keep having these unsafe abortions.”

He is just one doctor whose experience of illegal abortion before Roe v. Wade shaped his career and ethics. For some, it led them to put their own lives at risk.

Now Roe v. Wade has been overturned. Tennessee’s abortion law is one of the strictest in the country. The doctors we spoke to saw parallels between January 1973 and July 2023.

To be sure, there are important differences. A woman can have a baby on her own without being shunned, fired or expelled.

Illegal abortion now often means buying a pill off the internet, much safer than the old days. In 2020, 81% percent of abortions happened at 9 weeks or earlier, and 93% at or before 13 weeks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Medication abortions are appropriate before 12 weeks, according to the World Health Organization.

Some things haven’t changed.

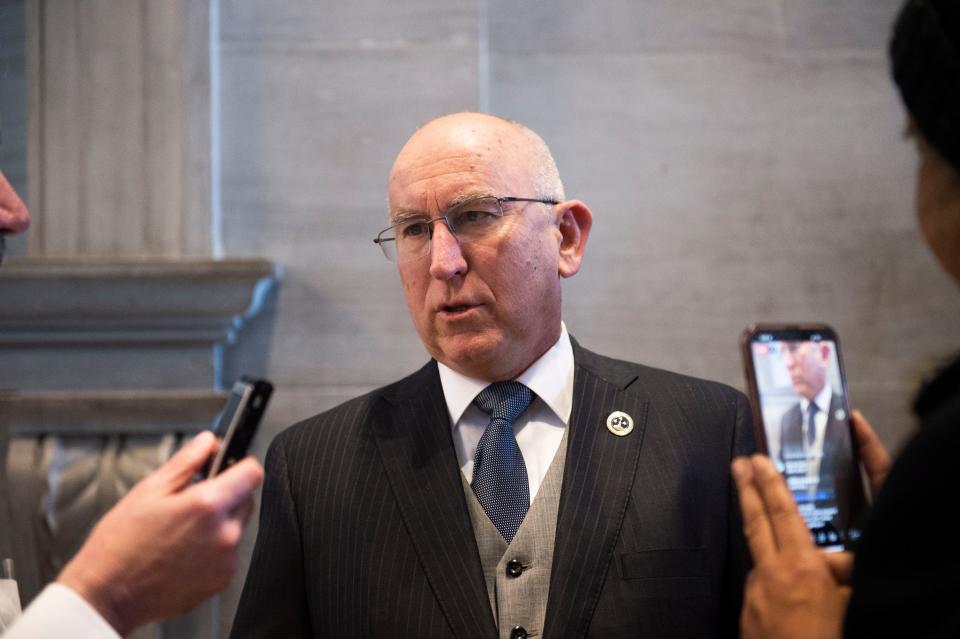

In the Tennessee General Assembly, a doctor-lawmaker argues to expand abortion access. Then it was state Rep. Dorothy L. Brown, first Black woman to serve in Tennessee’s legislature or work as a surgeon in the South. Now it’s state Sen. Richard Briggs, R-Knoxville, a heart and lung surgeon.

Women with money or savvy travel to other states to get legal abortions. There are networks in states like Tennessee to help women do that, or procure abortion pills. Low-income women are often stuck.

And these doctors are concerned now, as they were then.

“Pre-Roe v. Wade was not easy. And I fear that this new stage, even though it’s going to be safer maybe, not quite as traumatic, is causing a huge number of problems for patients, for doctors and for law enforcement,” Boehm said.

A brief doctors’ history of abortion

When Boehm started medical school at Vanderbilt in 1961, “abortion was never mentioned,” he said. “We were never trained in any of that.”

Still, there was wiggle room. Many hospitals, including some in Tennessee, would perform “therapeutic” abortions if a committee OK’d it. Some doctors stretched the law on their own. “You could have an abortion if your life was threatened — at least, nobody prosecuted you,” Boehm said. Some doctors would say their client had started miscarrying, and thus needed a dilation and curettage to empty the uterus, when maybe they really hadn't.

In 1967, the American Medical Association OK’d abortion “if the mental health of the mother was in danger, if the child would be born deformed, if the conception took place through rape or incest,” according to The New York Times.

State Rep. Brown’s 1968 bill echoed that language. The Tennessee Medical Association’s legislative chairman spoke in favor before the Tennessee House, saying that as things stood, “We, as doctors, are compelled to perform an act (abortion) that is contrary to the laws of this state,” according to The Tennessean, part of the USA TODAY Network.

The bill failed in the House by two votes and was scheduled for a revote when Brown announced it was fatally stuck in a Senate committee.

Still, the wheels were turning. In 1970, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists OK’d abortion “at a patient’s request,” according to an article by Nancy Arles.

“You have a right to make a decision on which way you want to go. I have no right to get involved in your morals,” Nashville General Hospital director John Zelenik told The Tennessean in 1972.

There were also doctors on the other side. “It’s murder, that’s the only way to look at it,” a Dickson doctor told UPI in 1973.

Then Roe v. Wade came down, making first-trimester abortions solely the mother’s decision.

A personal story: Dr. Susan Dodd

Susan Dodd was 16 in 1972 and knew nothing about pregnancy — when she got her period, she thought she was dying. Her boyfriend, a Gatlinburg, Tennessee, police officer, always used a condom. So her older sister had to tell her, when Dodd complained that her period had stopped and she felt unwell, that she was pregnant.

Dodd, her boyfriend and her sister went to Knoxville, Tennessee, to an ob/gyn who performed abortions after hours. It cost $500 — about $3,700 in today’s dollars. Her boyfriend paid.

The abortion changed her life. For the better. The teenager who knew nothing about pregnancy decided to become an ob/gyn.

Decades later, when the Knoxville abortion clinic’s only doctor died, Dodd took up the job. No one else would do it, she said. Her husband bought her a bulletproof vest.

“I really felt like this is a service that women in my community, around here, need to have,” she said. “I became an ob/gyn who performs abortion because I had one.”

Abortion in Tennessee after Roe

For the first 15 or 20 years, abortion was not controversial, doctors said.

Briggs did his ob/gyn rotation in the late 1970s. When someone wanted an abortion, “There wasn’t a whole lot of judgmental stuff or people counseling for or against,” he said. “Even though it had been totally banned, there didn’t seem to be as much of a stigma.”

Dr. Wesley Adams remembers, in 1973, surgery residents joking that they’d chosen the wrong specialty — given the demand they expected for abortions.

Practicing in Bristol, Tennessee, “we just kind of did them,” Adams said. Abortion was part of ordinary care for local patients, along with delivering babies, performing annual gynecological exams and arranging the occasional adoption. He eventually ran abortion clinics in Bristol, Nashville and Charleston, South Carolina.

But sentiment was changing again. In 1993, Dr. David Gunn was killed by an anti-abortion activist when walking into the abortion clinic he ran in Florida.

“He was my resident,” Boehm said. “He was one of the sweetest guys you’ll ever meet.”

A doctor’s story: Dr. Mary Jane Brown

Even doctors who only brushed the pre-Roe era are troubled by memories. Dr. Mary Jane Brown, a Murfreesboro, Tennessee, emergency physician, did her ob/gyn rotation in the late 1970s. She was pregnant herself, caring for women with complications from pre-Roe abortions.

“Women that were infertile. Women that had to have surgery and had complications from that surgery, like small bowel obstruction,” Brown said. Horrible abdominal scars. Ugly-looking cervixes that should have been a pearly pink.

“All last summer I had flashbacks,” Brown said. “I can no longer be silent. To be silent is to be complicit.”

Abortion ethics through doctors’ eyes

All the doctors we spoke to said they supported life. Had delivered thousands of babies, if not tens of thousands.

“There’s not a doctor or nurse I know who wants to do an abortion,” said Boehm, now a Vanderbilt professor emeritus.

“I believe in life — how can a physician not believe in a right to life — but I believe in life for everybody,” including the mother, Briggs said.

Some were comfortable with elective abortions. Briggs isn’t. Dodd challenged the distinction: If you’re financially desperate, “What makes that less ‘necessary’ than a fetal anomaly?” she said.

All had wrestled with the question of when a fetus becomes a person. For most, that was when it can survive outside the womb. Abortions after that point are extremely rare.

They also considered the ethics of their profession. A physician’s job is to provide the best care possible to the patient, they said. The patient should be in the driver’s seat.

“I’m not a woman,” said Briggs, who considers himself pro-life. “We don’t like imposing our values on people.”

More: How one quiet Illinois college town became the symbol of abortion rights in America

Abortion in Tennessee: What now?

Briggs regrets voting for Tennessee's 2019 abortion trigger law. “I didn’t understand it when I voted on it,” he said. This spring, he successfully sponsored a bill to make abortion legal for an ectopic or molar pregnancy, or to prevent the death or “serious risk of substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function of the pregnant woman.”

It still leaves too much out, he said, like rape or incest, and when a fetus won’t survive.

In the late 1960s, the physician establishment began speaking up for abortion access. Now, national groups such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists are, too.

Not all Southern doctors feel comfortable joining them. There are consequences. Tennessee Right to Life excoriated Briggs when he began criticizing Tennessee's law.

One retired ob/gyn talked about abortion for an hour, but only on the agreement that his name not be used. He wanted the facts out there, he said. But not at the risk of someone harming his family.

For these doctors, a Tennessee without legal abortion isn't new. It's history repeating itself. First there was no Roe v. Wade, then there was, now there isn’t.

“That’s the big lesson — that nothing is forever,” Boehm said.

Except, perhaps, women seeking abortions when they feel desperate.

“They’ll find a way to do it,” Boehm said. “And hopefully it will always be legal.”

Red flag for Republicans: Independent women at odds with GOP on abortion, LGBTQ rights

Danielle Dreilinger is an American South storytelling reporter and the author of the book “The Secret History of Home Economics.” You can reach her at ddreilinger@gannett.com or 919-236-3141.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Illegal abortions before Roe shaped these Tennessee doctors' careers