'I'm disgusted': Pastors slam Baptist seminary for 'hidden' marker noting ties to slavery

Louisville’s Southern Baptist Theological Seminary was founded 164 years ago by four men who all owned enslaved people.

But unlike other institutions of higher education, including Columbia University and the University of Cincinnati, which removed the names of slaveowners from its campus buildings, Southern’s president, R. Albert Mohler Jr., has refused to do the same.

He has called the seminary’s four founders “titans of their faith” and said two of them were “consummate Christian gentlemen, given the culture of their day.” Without them, he has said, there would be no seminary.

To make amends, Mohler and the seminary’s board promised to erect a “major marker” on campus that acknowledges the “sin of American slavery and the contributions made to this institution by countless slaves.”

And a plaque was hung three years ago.

But the controversy was reignited last month when an independent Baptist publication reported that a prominent Black pastor from Texas who visited the campus couldn’t find it.

Another Black minister, Derek Hayes of the Committed Church in Louisville, was quoted in the piece saying it was galling that the marker was hung in one of the very buildings named for an enslaver.

“The placement … proves at the least that @albertmohler is either culturally insensitive or ignorant,” Hayes wrote in the column, titled “Disrembering the Past.”

He and other critics note the plaque mentions the names of the slaveholders but not the names of any slaves.

In an email to The Courier Journal, Hayes, who attended Southern, called the plaque “hidden” and “pathetic.”

“As a Black man, I’m disgusted,” he said. “As a follower of Jesus, I’m disgusted. As a Christian pastor, I’m disgusted. As a student of the seminary, I’m disgusted.”

Mohler, one of the nation’s most prominent evangelicals and Southern’s president since 1993, did not respond to more than a dozen questions submitted to him through his spokesman and chief of staff, Caleb Shaw, who did not respond to calls and emails.

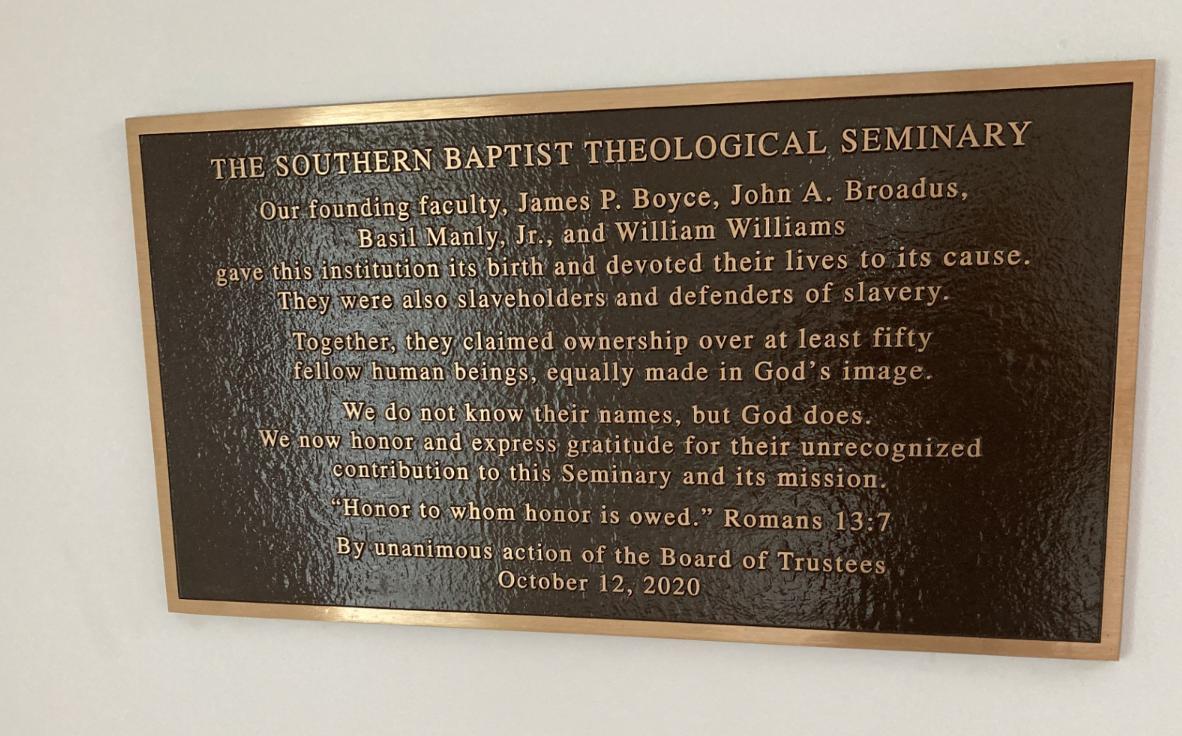

The historic marker, which is hung in the lobby of Broadus Chapel, measures about 20 by 30 inches — smaller than a banner flying nearby outside that bears a photograph of Mohler.

The plaque says:

“Our founding faculty, James P. Boyce, John A. Broadus. Basil Manley Jr. and William Williams, gave this institution its birth and devoted their lives to its cause. They were also slaveholders and defenders of slavery. Together, they claimed ownership of over at least fifty fellow human beings, equally made in God’s image.

“We do not know their names, but God does. We now honor and express gratitude for their unrecognized contribution to this Seminary and its mission.”

During two recent visits to the campus on Lexington Road, a reporter found that only two of 10 students and staff asked about the plaque knew what it was or its location.

The Rev. William Dwight McKissic Sr., senior pastor of Cornerstone Baptist Church in Arlington, Texas, who couldn’t find the marker, said he is grateful Mohler kept his word by erecting it. But McKissic, who successfully pushed the Southern Baptist Convention to issue resolutions criticizing the Confederate flag and condemning white supremacy, said he had hoped to find a memorial at the seminary “so prominent and visible that I couldn’t have missed it.”

McKissic told The Courier Journal the marker hardly compensates for the decision of Mohler and his board to leave the names of its slaveholding founders on its libraries and chapel.

“They obviously value the slave masters more than the slaves,” he said, adding:

“If the founders were abortion advocates, they would have no hesitancy in removing their names,” McKissic said.

The seminary and the Southern Baptist Convention have struggled for decades with their racist legacy.

In 1995, on the 150th anniversary of its founding, the convention’s leaders said it had publicly repented its roots in the defense of slavery.

In 2018 Mohler appointed a committee to report on the seminary’s evil ties with slavery and racism.

In a 71-page report, it found the seminary’s early faculty and trustees sought to preserve slavery and defended the Confederacy’s cause — using the Bible to justify white superiority.

It found that even after emancipation, the seminary opposed racial equality, supported the restoration of white rule in the South in the Reconstruction era, and championed segregation through the 1940s.

The report also said the seminary’s most important donor, former Alabama Gov. Joseph Emerson Brown, a former governor of Alabama who chaired its board of trustees from 1880 to 1894, earned much of his fortune by exploiting Black convict labor.

But the seminary’s response since the report came out has been seemingly inconsistent.

While trustees in 2020 removed Brown’s name from its oldest academic chair and pledged up to $5 million in scholarships for African American students over the next few years, the board voted unanimously to keep the names of its enslaver founders in place because of “their sacrificial service and historic leadership.”

Mohler himself wrote: “I stand with the founders in their courageous affirmation of Biblical orthodoxy.”

Hayes, pastor of the Committed Church, 2627 Crums Lane, said Mohler’s approach “is nothing more than Mohler “playing to his far-right, Trump-supporting base by putting forth a conscious and intentional effort to be dismissive and do nothing.” (After denouncing Trump during his 2016 presidential campaign as “beneath the baseline of human decency," Mohler reversed himself and endorsed Trump four years later.)

The Rev. Brian Kaylor, editor and president of Word&Way, wrote in his column last month that Mohler has shown himself to be “philosophically and theologically unequipped for moral reckoning that is needed.”

Kaylor, an author and host of the podcast, “Baptist Without An Adjective” has often clashed with Mohler, who has called him a “liberal nitwit.”

Kaylor has written that the seminary should construct an actual memorial at a prominent campus location — “not a little plaque on a wall.”

And he said Mohler needs to “say the names” of enslaved persons who involuntarily contributed to the seminary.

Kaylor said that would be a “meaningful corrective” and a “powerful rebuke to the system of white supremacy" that led to the birth of the seminary.

More: Rodents, mold and trash: Louisville housing agency a ‘slumlord,’ council member says

Reporter Andrew Wolfson can be reached at (502) 396-5853 or awolfson@courier-journal.com.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Louisville Southern Baptist seminary's slavery plaque called 'hidden'