I'm a journalist. Watching migrants struggle to cross the Rio Grande hit close to home.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The weight of July’s heat wave hadn’t set in yet that morning. Trees shielded us from the still-rising sun, but sweat still beaded on our skin. We’d been walking for more than an hour through the brushlands south of the Rio Grande.

Along with a colleague, El Paso Times photographer Omar Ornelas, I had joined a group of about two dozen Latin American migrants who were about to cross the river from Mexico to the United States. Two coyotes, or smugglers, led us on a twisting route that went from a paved street to dirt paths and, eventually, nothing but grass and shrubs underfoot.

Reporting from Piedras Negras, Coahuila: 'They're going to find a way': Migrants navigate buoys, razor wire to enter Texas

“Las noticias van por donde quiera, verdad?” one migrant said to me, smiling.

The news goes everywhere, right?

It’s true — journalists go anywhere to find the story. But this story hit close to home.

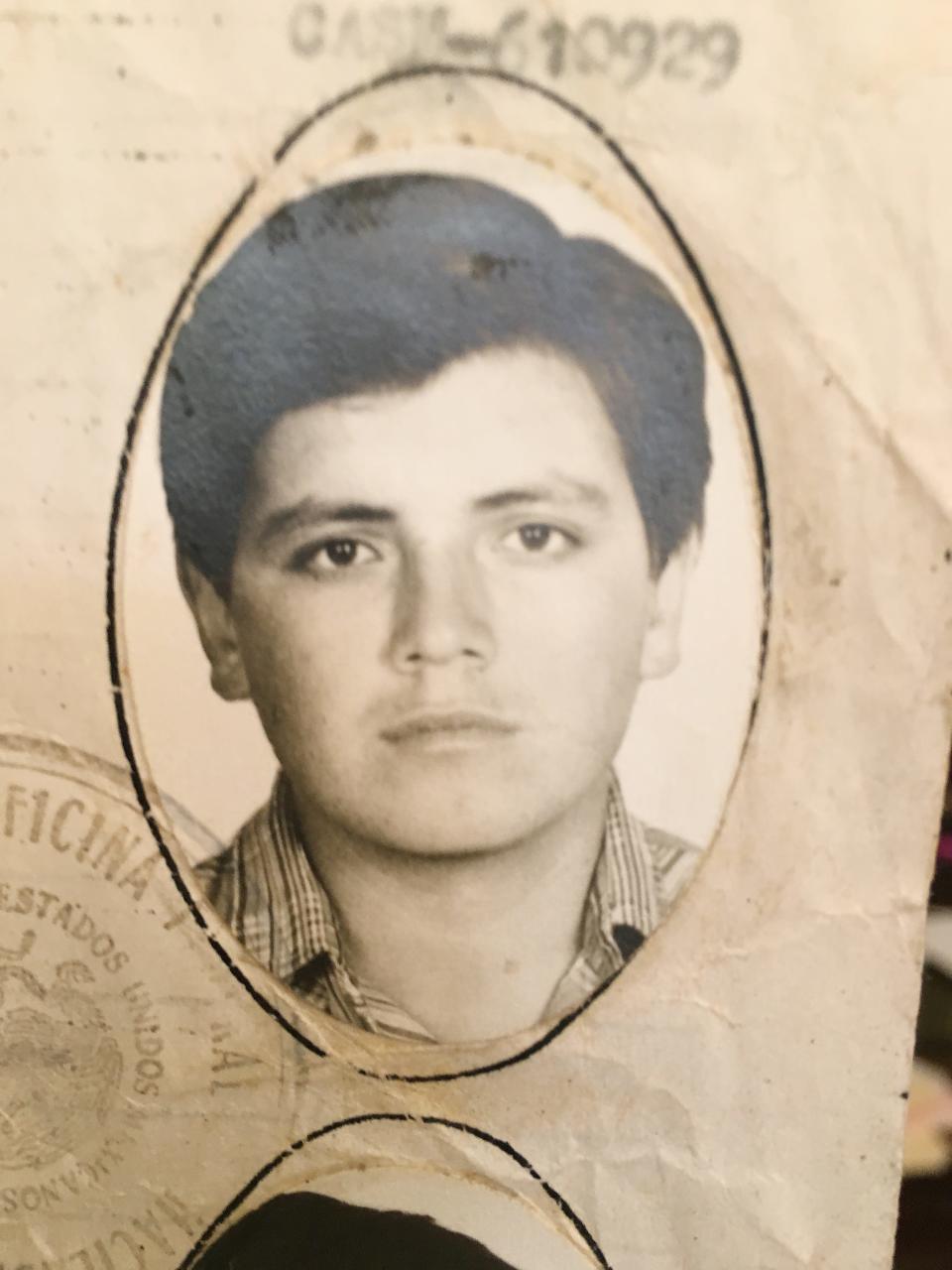

My dad, now 62 and an American citizen, crossed the Rio Grande illegally from Mexico at age 21.

The first time he crossed, he made it to the United States without incident, walking across a shallow river and illicitly jumping on a train to travel north.

After working as a pressman at a printing company in Houston, my father returned to Mexico to visit family and friends in Linares, Nuevo León. Then it was time to go back to work. He and some friends crossed the low river between the Mexican city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, and Brownsville. But immigration officials caught my dad and promptly sent him back. (They didn’t bother with deportation documents then, my dad said.)

My dad returned yet again. The Rio Grande is fickle — this time the water was so deep that he had to swim, struggling against the heavy current. That’s the thing about the Rio Grande. The current is so unpredictable, some migrants drown.

I’d read the news articles about migrants dying while trying to reach the United States. I grew up knowing my dad had made that trek over the river more than once. This month, for the first time, I watched from mere feet away as migrants crossed the river on foot.

While on assignment for the American-Statesman, I saw almost 30 people cross the river near the international bridges connecting the Mexican border city of Piedras Negras, Coahuila, to Eagle Pass.

The depth of the water varied as they walked across — up to their thighs in some areas, ankle-high in others — and the current was mostly calm.

But crossing the river could still be challenging. A group of migrants abandoned their backpacks on the Mexican banks of the river because the bags were weighing them down. One man coaxed a young boy to shed his bag, telling him, “Ya perdimos todo.” We lost everything already.

The next morning, I walked with migrants to a more remote part of the river. There, one of the smugglers said, the current was so strong that it would carry people away if they were not holding hands as they crossed. He said he had seen dead bodies floating down the river.

One of the people in this group was a skinny young boy, about 6 years old. He gripped the hands of adults on either side of him, but the current lifted his tiny body as easily as the wind blowing a feather. His legs splayed out behind him.

As he cried in panic, I felt sick to my stomach. But the migrants made it to the other side, where the water was more shallow and quiet.

I told my dad about it later. What I described didn’t surprise him; he knew the danger and the fear of the journey. It didn’t end after arriving on U.S. soil. He recalled being accosted by men who tried to rob him; he hid a bill of money inside his mouth so they wouldn’t steal it.

He took a taxi from Brownsville to Harlingen. The train was next. He hid in the brush of a mountain near the train tracks until the coast was clear, then ran and jumped into a space under a train car, just above one of the wheels. He could hear the footsteps of immigration officials passing by. He didn't dare move and, when the train began moving, used his pure strength to hold himself and avoid falling onto the wheel.

When the train stopped later, away from the vigilance of the Border Patrol, he climbed to the top of the train.

“Se me hace feo recordar,” he told me, “pero, pues, es la realidad.”

It’s ugly to remember, but, well, it’s reality.

Let me tell you a little about my dad, Miguel Camarillo.

For most of my life, I’ve wished I could be half as brave and generous as he is.

He’s the kind of guy who will pull over to help someone with car problems on the side of the road. He’s the kind of guy who easily makes a new friend in line at a taquería.

In the past few years, he’s taken to making breakfast for my mom and sisters.

He has loved baseball almost all his life; as a young boy in Mexico, he preferred it to soccer. Decades ago, watching Houston Astros games and listening to the commentary helped him improve his English.

He’s fun to have a beer with.

And he’s a resourceful, hard worker. He’s been working as a pressman for almost 40 years, coming home with ink dotting his hands and clothes.

My dad eventually gained permanent residency and later full citizenship. Don’t ask him when he became a citizen; he can’t remember. But it was likely by 1991. He sponsored my mom, who became a permanent resident the next year and gained citizenship in 1999.

I’m one of four daughters. Two of us have master’s degrees; the third is about to start a master’s program in the fall; and baby sister is starting her second year of college.

We’ve succeeded thanks to our own hard work and focus, but our parents set us on that path.

My dad’s story is not interchangeable with the stories of today’s asylum seekers, who are fleeing persecution and untenable lives.

But he crossed a temperamental river. And he saw the future: a better life not only for himself and my mom, but also for the children he would one day have.

Camarillo is the local news editor at the Austin American-Statesman.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Why covering this Rio Grande migrant story hit close to home for me