'I'm never going away:' In Big River, a decades-old grudge against the state is hereditary

WEST GREENWICH – Frank J. Lemaire proved prophetic in death, dying in 2007 in the family farmhouse he swore he’d never leave after the state took ownership of it – and his 400-plus acres of land – against his will.

By the time the ex-tree cutter passed on at age 78, his grievance was 40 years old. Yet anger still oozed from him like pitch from a freshly cut pine.

“How many times did my husband say, ‘I’m sitting on this porch with a shotgun in my lap and all my friends are going to be with me, and we’re going to keep everyone away from my land,’” his widow, Jo-Ann, recalls outside the old gray house. The summer wind swirls her hair. “I’d say, ‘OK yeah, you could do that, you could have the [news] papers here, you can get arrested, and then you’re still out, because they own it.’ But he died with that thought.”

After the state took their land, original residents live as tenants in their own homes

The state took, through eminent domain, Lemaire’s land and 8,100 more acres owned by 351 property owners in the early 1960s for a reservoir never built. But the state kept it all, explaining that the Big River watershed, now a management area enjoyed by thousands of outdoor enthusiasts, might be needed someday as a water source.

Some residents took the money the state offered for their property and moved away. Others stayed until the homes they no longer owned – and the state did not maintain – became uninhabitable and were razed. And some, like the Lemaires, balked at uprooting their heritage along Congdon Mill Road, where the tableau of a rustic farmhouse and field seems out of time and place, 20 minutes from urban sprawl.

Today, only four or five “originals” or their relatives still live in the Big River Management Area; tenants now who pay small monthly rents but suffer, they say, the indignity of regular visits from state safety inspectors: Is that mold on the walls? A leak in the roof?

If they don’t like what they see, “they can evict you with a 30-day notice,” Jo-Ann Lemaire says. “We walk around on eggshells.”

More on Big River: The Big River Reservoir project forced 351 people from their homes. Will it ever be built?

'I'm never going to go away'

Turns out a grudge is inheritable.

Almost 60 years after the land-taking began in Coventry, West Greenwich and the Wood River area in Exeter, Frank Lemaire Jr. carries on his father’s resentment from the same porch.

The state “would rather just tear down the few houses left here and be done with us all,” says the 42-year-old father of three. “They do not want us down here, because once all the houses are gone, now it’s a weight off their shoulders."

“But I'm never going to go away. I’m always going to be a thorn in their side, because they did a lot of people wrong. You steal something from somebody and they’re going to hold a grudge. And there is a grudge so built into me.”

Four miles from the Lemaire house, 96-year-old Marilyn Albro sits in the darkened kitchen of her home on Nooseneck Hill Road, a counter fan cooling the air.

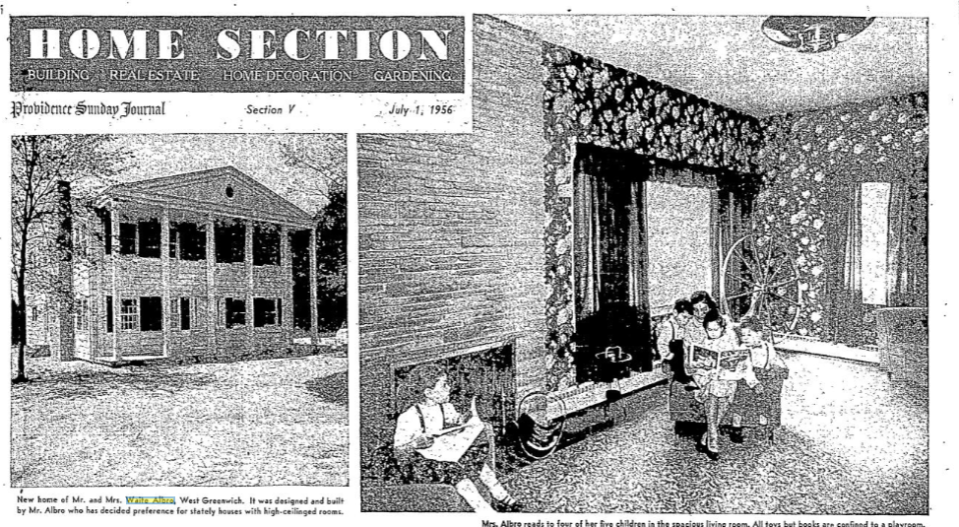

In the summer of 1956, a Journal reporter and photographer came here for a Sunday Home section story, taking pictures of the new Southern-style house with its six tall columns out front. Marilyn’s husband then, Waite Albro, designed the house himself and built it with relatives.

Marilyn Albro looks down at a copy of the old newspaper story, with photographs of the sturdy white structure, the impeccable interior, the sweeping staircase, and of herself sitting in the high-ceilinged living room with three of her seven children in her lap. Her eyes begin to tear.

Two of her children, Waite Albro Jr., 70, and daughter Joni Albro, 65, were outside a few days earlier, sitting near the tall butterfly bushes and purple passionflowers Waite has grown over the years in a yard that's technically not his. Plump blackberries droop over the trail he still mows that leads to the collapsed barn peeking out from under a green shawl of briars.

What happened in Big River – or, more precisely, what didn’t happen – remains “a sore issue, definitely,” says Joni. The state bought the Albro farm, “telling us we had to sell it to them – and then they didn’t do anything with it. But they never stopped to say, ‘You know what, let’s see if people want to buy their property back.’”

What happened – or didn't – at Big River?

State planners conceived of a Big River Reservoir in 1928, two years after the Scituate Reservoir was finished. But it wasn’t until 1964, in the midst of consecutive years of drought, that state voters approved a $5 million bond to acquire the land.

It was to take seven years to build all the dams and three years to flood about 3,700 acres of the condemned land with water as deep as 40 feet. Some engineers with the state Water Resources Board would spend much of their careers working on the $282 million project, until the federal Environmental Protection Agency ultimately vetoed it in 1990, saying the loss of 575 acres of wetlands outweighed its benefits.

Frank Lemaire and a few other landowners sued to get their land back and lost. And in 1993, the General Assembly passed legislation designating the Big River area preserved open space until such time that a reservoir is needed.

“It was very happy and magical here until the reservoir,” Waite says, meaning when the project first intruded on their lives. “We had a huge farm here. We raised cows, turkeys, chickens, pigs – and did all the processing ourselves. Mom used to cure the bacon downstairs.”

State inspectors descend on Big River land

In 1991 West Greenwich celebrated its 250th anniversary with a parade down Nooseneck Hill Road. By then, many of the houses of Albro’s neighbors had fallen into disrepair.

As Gov. Bruce Sundlun marched along the road with town officials, he turned to then Town Council President Kevin Breene and remarked about how decrepit the houses looked.

“Well,” Breene replied, “you own 'em.”

Soon enough, Sundlun directed a home inspection program for the houses remaining on Big River land. Within the next 18 months, residents of four Nooseneck Hill Road households were served eviction notices after inspectors found unsafe structural, plumbing and electrical violations that were beyond repair.

“Oh, they brought in the asbestos lookers, the lead paint searchers, the mold exterminators,” says Waite. “They brought in everybody. They made my father and I tear down walls in three corners of the house” looking for structural problems. “There was nothing wrong with it. But they really thought they were going to find something. They were really trying to get us out of here at that point.”

Such past experiences have bred a lasting mistrust through these piney hollows.

Will Big River ever be developed?

No matter that the law today says Big River must be preserved as a future water source, Joni Albro is convinced the state will someday develop portions of it: “The land is just too valuable.”

There have been past encroachment attempts, most notably in 2005, when former Gov. Donald Carcieri eyed 18 acres of Big River land along Interstate 95 as a site for a new state police headquarters.

Environmental and water-resources advocates vehemently objected, and Carcieri backed off.

And Quonset Point developers once hoped to take Big River sand for an industrial park before they, too, were warned they’d be opening a painful wound – and years of legal wrangling.

Meanwhile, the state Water Resources Board announced this summer that it was developing a plan to manage recreational use inside the Big River Management Area to preserve its water “quality and quantity ... as a future drinking water source for the state of Rhode Island.”

The plan, to be completed in the fall of 2024, will evaluate “access points, security, roads, trails, natural resources, and land management practices.”

Breene, a cousin of the Albros and the former Town Council president when he walked with Sundlun in that parade, is now West Greenwich’s long-serving town administrator. His family’s roots in town stretch back centuries, and he’s lived with the Big River saga all his life.

His father, a farmer, lost 200 acres to the reservoir project in the 1960s, and when Breene wanted to buy his own dairy farm later, he ended up having to buy land outside the management area. “I’d rather be down on Big River.”

“I always felt bad, because some people had some beautiful places and figured they had to get right out because the reservoir was supposed to be built in the early '70s. Some of the people who were older could have just stayed there, the way it all turned out, and finished out their lives where they were happy.”

Who will remember what happened?

A few months ago, Breene says he testified before a legislative committee about a proposal that surfaced to use land around the Scituate Reservoir and in the Big River watershed for affordable housing.

Breene had to explain to lawmakers why that couldn’t be done, and the law that preserved Big River as open space until such time as it’s used as a water source.

“There is very good case law," he says. "That land was condemned for the purpose of a reservoir, and to use it for anything else – even one acre of it for something else – you would have to offer all the land back to the original inhabitants or their heirs. You would have lawyers coming out of the woodwork. There’s no sense to even talking about it.”

Breene says, “I always tell people it was a terrible thing if you lived there. You read about the Scituate Reservoir and how people were beside themselves and how they tore villages down. But at least they built it.” That wound had a chance to heal. In Big River, the hurt is always fresh because “they took all our land and never built it.”

“On the positive side,” he says, “if it wasn’t condemned for a reservoir, it probably would have been developed and there would be 20,000 people living in West Greenwich now” as opposed to 6,300.

More: Scituate Reservoir came at a cost, including lives. Film explores how we're still paying

But Breene, who is 67, worries about the future. What if younger generations never learn the Big River story?

There are only a few “originals” left, like Marilyn Albro. “Then there’s my generation. We were little kids when the whole thing got condemned. We're all getting older. It will only be a matter of time before nobody realizes exactly what really happened here and why it happened. And what didn’t happen.”

Back on Congdon Mill Road, Frank Lemaire sounds much like his late father.

“My field” beside the house needs attention, he says. He mows it every year, but the woods appear to be creeping in, particularly down at the far end, where his grandparents lived before a 1938 fire destroyed the original farmhouse.

He shakes his head, catching his mistake. “I say that all the time,” he says. The field isn’t his, of course, any more than the house here at the other end of the field, the house his grandparents rebuilt after the fire, where his father and mother raised a family, where he is now raising three children of his own.

These days he runs into people he went to school with at his children's various events.

They ask him if he’s still living in town.

“Yep,” he says, “Still living at the farm.”

They seem surprised.

But Frank Lemaire isn’t going anywhere.

Contact Tom Mooney at: tmooney@providencejournal.com

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: After their land was taken for Big River Reservoir, these families don't forgive