'I'm not convinced we will have fair elections in America': Stacey Abrams' fight against voter suppression

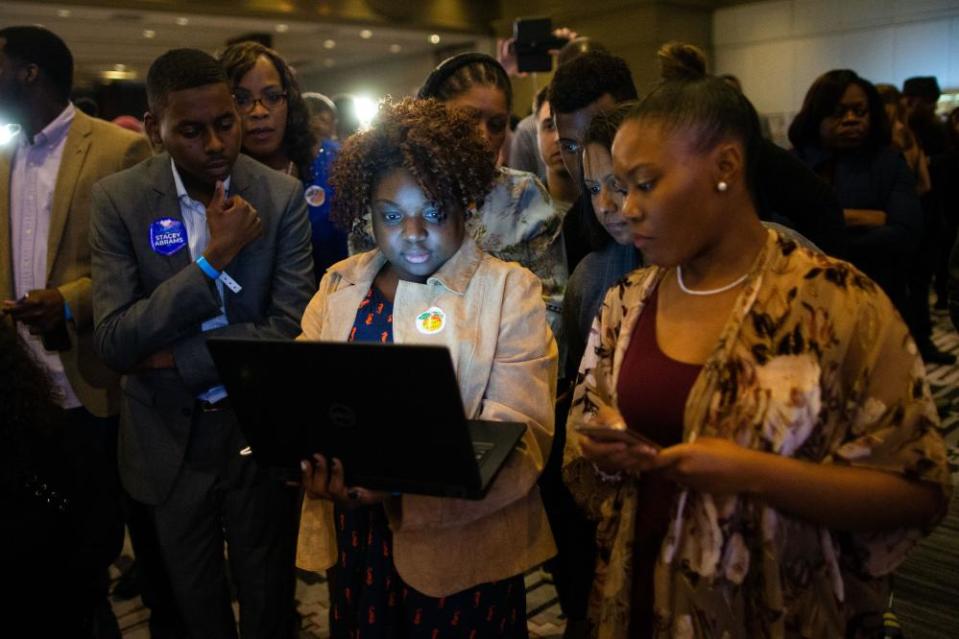

One year ago, at an election night party in downtown Atlanta, Stacey Abrams took the stage and delivered a speech that could well have been made 60 years ago, when this city was known as the cradle of the civil rights movement.

“Democracy only works when we work for it. When we fight for it. When we demand it,” she said, the microphone peaking under the power of her voice. “In a civilized nation, the machinery of democracy should work for everyone, everywhere. Not just in certain places. And not just on a certain day.”

Abrams was then the Democratic candidate for Georgia governor, attempting to become the country’s first black female state executive.

The race captivated America not only for its potential to make history. It also dredged up the country’s darkest past. African Americans in the deep south were once disenfranchised with literacy tests and other racist laws, and in recent years a surge in restrictive voting legislation, including voter identification laws and sweeping electoral roll purges, has ushered in an era described by some as a neo-Jim Crow.

Abrams did not win that night. Her opponent, the Trump-endorsed Republican Brian Kemp, eventually edged to victory by a thin, 55,000-vote margin. Abrams believes that voter suppression played a central role, which has led her to her next chapter: she has announced that for the next year, she will lead a nationwide voting rights campaign.

Her goal is to export lessons she learned fighting voter suppression in Georgia, and to mobilize a base of progressives and marginalized communities to help Democrats win the White House in 2020. While many had urged her to consider a run for the presidency herself, she believes the new mission may be a more formidable undertaking.

“I am not convinced at all that we will have free and fair elections unless we work to make it so,” she said in August, during the first of several conversations with the Guardian. “In America, we have the theory of free and fair elections, but unfortunately we’ve seen, particularly over the last 20 years, an erosion of the ability to access that right.”

The turning point came in a 2013 supreme court ruling that gutted the civil rights movement’s crowning achievement, the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The ruling paved the way for a raft of state laws that have made voting harder across the country.

“The vote is the most powerful nonviolent instrument of transformation we have in our democracy,” said the Georgia civil rights veteran and US congressman John Lewis last year. “There are forces trying to make it harder and more difficult for people to participate. And we must drown out these forces.”

This is why today, the Guardian is launching The Fight to Vote, a series that will investigate why it is so hard for growing numbers of Americans to cast a ballot. In the run-up to the 2020 election, it will scrutinize compromised electoral systems, give a platform to voices silenced at the polls, and reveal how voter suppression is already shaping the 2020 election.

“We are in a different era of voter suppression,” Abrams says. “But unfortunately it is a continued lineage of voter suppression that began with the inception of our country.”

****

We first meet on a bright and humid summer’s afternoon in an upmarket Atlanta suburb a few blocks from the headquarters of her new national voting rights campaign, Fair Fight 2020.

The campaign is now in its infancy, but aims to create a vast voter protection drive across the country, supporting teams in 20 battleground states to aid with registration and boost turnout among minority groups next year.

In September she appeared on stage at a concert with the pop artist Lizzo in New York, delivering a rousing speech urging young attendees to become part of the campaign. This was part of a broader goal of engaging younger communities of color by pushing the voting rights struggle into popular culture.

“Every one of you is responsible for finding a rule that is wrong,” she told the crowd. “I want you to break that rule and write a new one.”

Abrams sees this work, and her gubernatorial election last year, as the continuation of a struggle that has spanned generations. “We believe in the right to vote, but, from the very beginning, communities have been distanced from it,” she says.

Communities like her own. Born in the small, coastal city of Gulfport, at the southern tip of Mississippi, Abrams and her five siblings were taught about the critical importance of voting from a young age. Her parents, both Methodist ministers, were involved in the civil rights movement as teenagers – her father was arrested for assisting voter registration in black communities while still in high school.

“My parents took us with them when they voted,” she says. “They talked about why politics mattered. They made certain we watched the news and asked questions, because they wanted us to understand that our engagement, our ability to shape our communities, was directly tied to our votes, and they were very clear that they expected us to be voters.”

The voting rights struggle has shifted significantly since her parents’ days. While voter suppression laws in various states no longer explicitly target particular groups, the method is more insidious, using carefully constructed policy to make it harder to register, to cast a vote and to have a ballot counted. It has fundamentally changed the electoral landscape in the United States.

Abrams’ home state of Georgia is an incubator for these new suppression tactics, and Kemp, her opponent last year, is a primary instigator. Beginning in 2010, he served as Georgia’s secretary of state, overseeing voting and elections, and controversially declined to step down from the post while he ran for governor, meaning he effectively oversaw his own election.

Since the landmark supreme court decision, which allowed states to impose new voting laws without federal approval, Georgia has enacted a swath of voter suppression laws, from rapidly purging the voter rolls of those deemed inactive, to the closure of hundreds of polling places, often in poorer black neighbourhoods. It introduced a new law terminating voter registration four weeks before the 2018 election day, preventing an estimated 87,000 people from voting.

The state also introduced a controversial “exact match” law requiring that details on new voter applications match precisely with government-issued documents – meaning an errant hyphen or a changed married name can block the registration process. This system proved contentious last year after 53,000 applications – mostly from African Americans – were revealed to have stalled less than a month before election day.

“We saw an implementation of almost every possible iteration of voter suppression,” Abrams says. “Yes, we became an incubator, but we also became a singularity where almost every one of those pieces [of suppression] was implemented by the person who would go on to become governor of the state.”

Abrams accepts she cannot prove empirically that these policies altered the election outcome. But she also refuses to rule it out, and she has not formally conceded the election, a move Kemp’s campaign branded “a disgrace to democracy”. It is a slur she shrugs off as hypocritical posturing. Kemp, privately educated and wealthy, is to her a representative of the sort of conservative, white patriarchal power she has spent much of her career fighting against.

“Brian Kemp is emblematic of what is happening across this country, which is that a community that has enjoyed a certain hegemony finds their control of power weakening,” she says.

Critics have leveled the same charge at Donald Trump, who himself has spent much of his presidency casting false and inflammatory allegations of widespread illegal voting, the central justification for many voter suppression laws across the country. The president even appeared with Kemp during the 2018 campaign and reiterated a number of the conservative attacks on Abrams: that she had encouraged undocumented migrants to vote, would support widespread firearms confiscation, and was at the helm of a “radical” agenda across other areas of public life.

Nonetheless Abrams’ success at mobilizing a progressive base means that many observers now see Georgia, a Democratic stronghold until the late 90s, as a swing state once again.

“She galvanized the most Democratic voters we’ve ever seen in Georgia,” says Tharon Johnson, a veteran Democratic strategist in the state. “She was able to get a lot of sporadic voters who historically don’t come out in gubernatorial races, to turn out. She went to low-propensity voters – folks that have moved or maybe fell off the voting rolls. I think the operation and apparatus she built then will be used to help elect a Democrat [next year].”

‘She always had plans and knows what she wants to do’

Abrams began to find her own political voice in the early 1990s, while studying at the historically black Spelman College in Atlanta.

She led organizing efforts when an unarmed black man, Rodney King, was assaulted by Los Angeles police in 1991. She appeared on TV news, dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, alongside the city’s first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, where the two sparred over Atlanta’s policing tactics. Jackson later gave Abrams her maiden job in politics as a research assistant for the city.

It was also at Spelman that Abrams begin to organize her life into a series of formal goals. Spurred by a romantic breakup at the time, she started entering her ambitions into a spreadsheet. By 24, she aimed to write a bestselling spy novel. By 30, she would become a millionaire. And at 35, the mayor of Atlanta. Her goals shifted over time – she published eight romance novels rather than spy novels, and she was elected to the Georgia house of representatives in 2007.

“Stacey has always been very, very direct,” says her youngest sister, Jeanine Abrams McLean. “She always had plans and knows what she wants to do and develops plans to make sure it gets done.”

As leader of the Democratic minority, Abrams earned bipartisan respect for her practical approach to governance..

“She may be the most brilliant woman or person I’ve ever met,” says Allen Peake, a former Georgia house Republican who supported Kemp in 2018. “She is incredibly intelligent, incredibly quick on her feet, incredibly well prepared for every political battle she enters.”

Peake mentions the time Abrams rallied Democrats to support a medical marijuana bill he worked on, as well as numerous GOP budgets passed with her support. “She was very pragmatic,” he says. Even so, he remains critical of her 2018 platform, which he characterizes as “radical”.

Kemp’s tenure as governor, meanwhile, has proved disastrous for progressive causes in the state, among the most rapidly diversifying in the country. He signed one of the most restrictive abortion laws in America and has refused to expand healthcare provisions, despite polling indicating a majority of Georgians disapproved of both decisions.

Abrams describes this as a “tyranny of the minority” – suppressing the vote, she argues, has led to the suppression of the views of the majority.

‘It is not possible to win by only talking to those we’ve talked to before’

There is an arresting passage in Abrams’ autobiography, Lead from the Outside, describing the doubts she battled as she announced her gubernatorial candidacy. Some of her closest friends and mentors declined to back her bid. Their message was blunt: Georgia was not ready to elect a black woman to high office. Abrams almost dropped out of the primary after one close mentor, who she does not name, declined to support her.

“I became more and more afraid, reluctant to do the work of campaigning because I didn’t want to pick up the phone and hear another person I admired tell me my skin color and gender would be my undoing,” she writes in the book, which was published before last year’s election.

Even though she is pouring her energy into fighting voting suppression, and has been touted as a potential running mate for Joe Biden, those feelings are still “devastating”.

“It remains a reason that I have people I thought were friends that I acknowledge now weren’t true friendships. A number of them came back after I won the primary, but it’s a conversation that helped me understand that this is not simply a trope held by those who oppose me as a Democrat. It was a trope held by those who just didn’t believe in the capacity of communities of color to hold power.”

The Democrats are hoping to win back the mostly white voters who swung to Trump in 2016, yet Abrams argues that embracing ostracized communities of color is essential.

“Identity politics is good politics for Democrats,” she says. “It is not possible to win and to build the coalitions we need to build by only talking to those we’ve talked to before.”

Abrams laughs a little awkwardly when asked if she has been approached by any of the candidates. “No one has rung my phone yet.” But she remains open. “I think it would be fantastic to be invited to be someone’s running mate, but you can’t plan your life around someone else’s wishes.”

Meanwhile, Abrams still maintains those spreadsheets she started writing back at university. She last updated one in February of this year. She struck off “Governor of Georgia by 2018” from the list, and updated it to include her forthcoming work on voting rights.

But she didn’t touch one goal that has been on there for years : president of the United States by 2028. “It’s still on there, but for later,” she says.

To contact the Guardian’s voting rights team, email votingrights@theguardian.com