Imagine what it was like in Austin when famed short-story writer O. Henry lived here

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

One of the most famous writers in Texas history is rarely identified as a Texan.

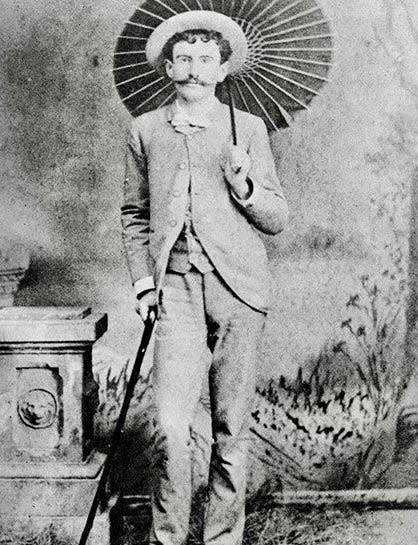

William Sidney Porter, who wrote under the pen name "O. Henry," was one of the most widely read American authors during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He attracted an international following for his finely crafted short stories that often ended in ironic "O. Henry twists," perfect for readers of popular magazines, newspapers and, later, books.

Yet outside Austin, where he lived from 1884 to 1895, few Texans claim him. Originally from North Carolina, he is little celebrated in La Salle County, where he spent two years working (sometimes) on a South Texas ranch in thorn brush country, or in Houston, where he lived briefly before being tried and convicted of bank embezzlement in Austin.

More: Texas history: On second thought, make that 60 essential books about our state

Instead, Henry is often considered a New York City writer, since he lived in hotels there periodically after he was released from prison, and he set many of his stories in that city.

In Austin today, Henry's name is attached to a small museum, a middle school, literary contests and other landmarks.

This is new: Feb. 17-25, Austin Shakespeare is set to bring nine of Henry's short stories to life on the stage of the Rollins Studio Theatre in the Long Center for the Performing Arts. Some of scenes are clearly set in Texas.

The arrival of this welcome show raises the inevitable question: What were Austin and Texas like when Henry lived here?

Which O. Henry short stories will I see onstage?

Ann Ciccolella, artistic director of Austin Shakespeare, has been a lifelong follower of Henry.

"Since I read him when I was a kid in Hoboken, New Jersey, I've adored O. Henry because his endings were so bouncy and unexpected," Ciccolella says. "I loved living in his world!"

More: 'The Bard is only the beginning': Austin Shakespeare expands its horizons

Most of the stories she read, however, were set across the Hudson River in New York.

"It was't until I moved to Austin that I discovered that O. Henry lived in Austin for (some) 10 years and a number of his almost 400 stories (were) set here," she says. "Now I hope we will celebrate his high spirits with audiences. Some stories folks will know, but there are lots of ones that will be new to them."

More: The darkly funny side of O. Henry revealed

These are the nine staged stories:

"Cupid A La Carte": A man and a woman grow closer while disagreeing and then agreeing about food.

"Pimienta Pancakes": In a camp, the subject of pancakes divides the workers.

"Witches’ Loaves": In downtown Austin, a woman who works in a bakery wants to please an artist who buys loaves of stale bread.

"The Cop and the Anthem": A homeless man searches for shelter for the winter.

"The Ransom of Red Chief": Crooks kidnap a 10-year-old boy, who proves more than a little hard to handle.

"To Him Who Waits": A hermit is tempted out of his cave by a woman.

"The Last Leaf": A painting plays a role in saving a life.

"A Retrieved Reformation": A detective tracks down an expert safe-cracker, only to find him transformed.

"The Gift of the Magi": A loving husband and wife plan to buy each other special Christmas gifts, with unforeseen consequences.

Austin grows from a town into a city

At the time of the Civil War, Austin was a mid-sized frontier town of fewer than 4,000 residents. It doubled as the state capital. By the end of the 19th century, it was a small, still somewhat provincial city of some 20,000.

Its first foundation was built on its role as capital of the Republic of Texas in 1839. It consisted of mostly log structures strung along either side of Congress Avenue and along the bluff above the Colorado River.

More: The puzzlement of Austin’s original city plan

By 1860, buildings were increasingly being made of stone, brick or sawn boards. Streets and roads were muddy or dusty, sometimes impassable by wheeled vehicles. Most businesses were built around cyclical governmental functions, such as the management of public land in the vast but underpopulated state, as well as housing, feeding and entertaining the legislators and other officials.

The quantum leap came with the arrival of the railroad in 1871.

Here comes the railroad

On Christmas Day 1871, a miracle made its way across Waller Creek at what is now East Fifth Street — a train. For the first time, Austin was connected to the outside world by reliable transport.

Previously, people journeyed to and from Austin primarily on foot or by horseback, stagecoach or oxcart. Roads and bridges were primitive. Residents relied on mostly local farm products and building materials. The city was cut off socially and culturally from the rest of the country and the world.

More: Austin’s first railroad altered the city forever

The first tracks (Houston & Texas Central) came in from the east and connected the city to coastal ports. The second (International & Great Northern) arrived from the northeast and extended south to San Antonio. The third, a modest line (Austin & Northwestern), connected the city to the upper Hill Country; it was used to bring in the granite blocks for the 1888 Texas state Capitol.

With the trains came luxury goods, heavy building materials, tourists and more immigrants. Austinites could export local crops, such a cotton grown on the Blackland prairies, as well as agricultural products that could be canned and shipped.

Along with railroads came telegraph lines, which instantly connected Austin with a world of news. Faster communication made trade, banking and finance easier. The same year that the first train arrived, this newspaper was born as the Democratic Statesman.

More: The Statesman has had more than a dozen homes

On a cultural note, trains brought theatrical troupes, musical groups and all sorts of celebrities. By the end of the century, locals were being inspired by these tours to produce their own literary, artistic, musical and theatrical efforts.

Henry, for instance, not only sang in the Southern Presbyterian Church choir, but also performed with a roving quartet and appeared in comic operas.

Finally, a second social, economic driver

The year before Henry arrived from South Texas, the opening of the University of Texas in 1883 meant Austin had acquired a second engine of social, cultural and economic development. Although classes were at first small, male and exclusively white, UT grew into a behemoth that spawned businesses and produced graduates who became civic leaders. It imported faculty members from places already blessed with universities.

Even today, one need not travel far to witness how a college or university changes a Texas town, or any town. Students, teachers and staff generate new tastes in food, clothing, entertainment and architecture. A law school or a medical school increases a small city's stature and power. A winning sports program becomes its own far-reaching powerhouse.

More: Before Austin was Austin: What you need to know about the early history of the Texas capital

Added to the majesty of UT's original Gothic Revival Old Main Building, during this decade the city welcomed its first luxury inn, the Driskill Hotel, in 1886, and a new domed state Capitol, the largest building for hundreds of miles, in 1888.

It must have been a thrilling time for Henry and the rest of Austin.

'Pittsburgh of the Southwest'

Once Austin had tasted higher education, social leisure and material comforts, it made, during Henry's time here, a stab at urbanity in the business sector.

By the late 19th century, manufacturing was the key to producing wealth. After all, the world was more than 100 years into the Industrial Revolution. Although Texas would remain predominantly rural until World War II, Houston, Dallas and San Antonio, along with Austin, Waco and Fort Worth, competed to recruit industries.

Manufacturing requires energy. This part of Central Texas held scant coal deposits, and the state's vast hidden stores of oil and gas would not be exploited until the 20th century. Water power was the obvious choice, and city leaders attempted to tame the Colorado River at the same site as today's Tom Miller Dam.

Hydroelectric power provided (unreliable) electricity for factories, lit buildings and streets and replaced mule-drawn streetcars. All this happened during Henry's time in Austin.

More: Flash floods inundate Central Texas history

In 1900, after he left, a big flood washed out the Austin Dam. What had been advertised as the "Pittsburgh of the Southwest" became instead a "Home City" or a "City of Homes," envisioned as leafy neighborhoods laced around two reliable sources of human energy — the government and the public university, along with private colleges such as what became Huston-Tillotson and St. Edward's.

With waves of newcomers, a city transforms

Early in its history, Austin was primarily an Anglo-American settlement, with immigrants arriving from the Upper South and the Gulf Coast, along with enslaved and free African Americans. The Native Americans who had preceded them on this land, the Tonkawa, were generally friendly with the new Texans, and even camped in what is now Republic Square Park. Mexican Americans, who had been expelled for suspected abolitionist sympathies during the 1850s, did not return to Austin in great numbers until turn of the century, and again during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920).

More: 'We're home': 140 years after forced exile, the Tonkawa reclaim a sacred part of Texas

Among the newcomers were Europeans from places such as Germany, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, including our distinct Lebanese population. (Many of them are buried in the recently revived Mt. Calvary Catholic Cemetery off Interstate 35.) Before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a small number of Chinese workers, whose cheap labor was key to building the transcontinental railroads, settled here, including the Lung family, who founded a string of popular eateries.

In addition, independent, land-owning African Americans made a huge impact during this time by founding freedom colonies on the verges of town — north, south, east and west. These communities were not segregated, but their Black schools, churches and businesses uplifted generations of African Americans who went on to help lead the civil rights movements of the 20th and 21st centuries.

More: Clarksville and Wheatville were not Austin’s only freedmen towns

The presence of such diversity pops up in Henry's stories. For instance, several of the characters in the Austin Shakespeare show speak German, or with German accents, which was common in Austin until World War II. An African American, rendered with a cringe-worthy dialect, shows up in "To Him Who Waits."

In 1884, Henry arrived in a place where the dangers and discomforts of the frontier were recent memories. Yet the confluence of rail links, higher education, progressive businesses, more leisure time and increased diversity were forging a city that he last glimpsed on his way to prison. A model inmate, he was released after serving three of his sentenced five years in the Ohio State Penitentiary.

'O. Henry Stories'

When: 7:30 p.m. Thursdays-Saturdays, 3 pm. Sundays, Feb. 17-25

Where: Rollins Studio Theatre, Long Center for the Performing Arts, 701 W. Riverside Dr.

Tickets: Start at $27

Info: austinshakespeare.org

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today Network paper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Author O. Henry lived and wrote for more than a decade in Austin