‘Imagine if Batman was your granddad’: Unsung heroes the Tuskegee Airmen get the Lucasfilm treatment

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

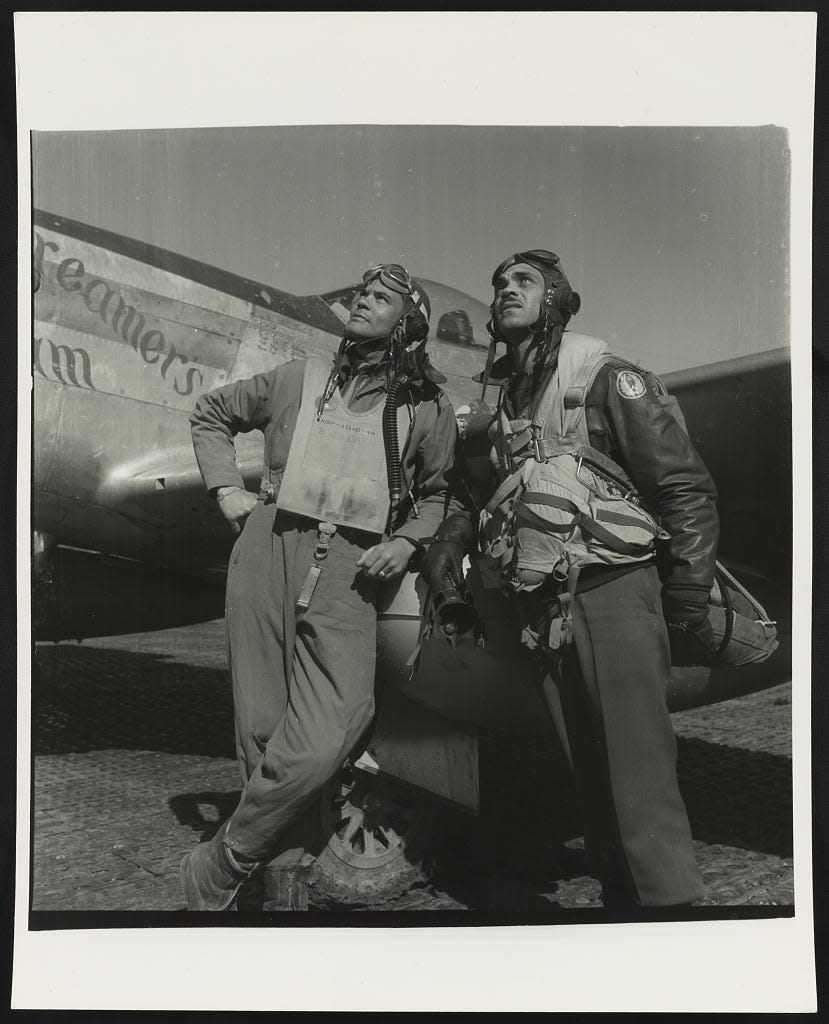

Lucasfilm is taking a step outside the sci-fi realm, trading in X-wing starfighters for P-51 Mustangs.

The production company behind “Star Wars” has announced that it’s launching an educational initiative celebrating the Tuskegee Airmen, the Black military aviators who overcame segregation, prejudice and hate to serve in World War II, yet whose story seems to have been lost in American history.

The documentary “Double Victory: The Tuskegee Airmen at War” is now permanently available on Lucasfilm.com, along with an educational curriculum guide for grades 6 through 12. A social media campaign aims to raise awareness of the airmen’s story with the hashtag #FlyLikeThem.

Much like the Harlem Hellfighters and Buffalo Soldiers, all-Black regiments of the U.S. Army who served in World War I and on the Western frontier after the Civil War, respectively, the Airmen fought the same enemies as their white counterparts, but received less attention.

“I use four P’s when I talk to young folks: perceive, prepare, perform, persevere, but persevere is so important,” says retired Gen. Charles McGee, who at age 100 is one of the last living Tuskegee Airmen. “Don’t let somebody tell you you can’t do something.”

So much of what Black men and women went through in that era is in danger of being forgotten, says Doug Melville, whose great-uncle Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. was the first African American general in the U.S. Air Force and a commander for the Tuskegee Airmen. “Because we could not write, because we could not read, because we did not own our environments, a lot of the stories have fallen through the cracks, been overlooked, been deleted … becoming invisible almost.”

He recalls his uncle, who died in 2002, as a teacher and a positive force, one who “was so regimented in his daily life.” But the general didn’t earn his respect without adversity: While studying at the U.S. Military Academy, he was an outcast, having little social contact with his peers because of his race.

“The story of him going to West Point for four years without any human interaction is a story that no one could really understand how he did it,” says Melville, chief diversity officer at TBWA Worldwide, a global advertising company.

Davis wasn’t alone in his experiences. To be stationed in Tuskegee, Alabama, where the group trained and took its name, was to be stationed in the heart of hostility, where one step off campus could prove treacherous.

“Other cadets who grew up in the South let us know what was safe to do and what not to do,” McGee recalls.

McGee, one of the first pilots to graduate from Tuskegee, served for more than 30 years, fighting in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. His first assignment was with the 332nd Fighter Group in 1944, escorting heavy bombers from the 15th Air Force over Europe. He flew 137 combat missions in WWII and was promoted in February from colonel to brigadier general by President Donald Trump.

McGee hopes the example of the Tuskegee Airmen can last for subsequent generations.

“We were thankful for the opportunity and that the experience we developed and the values and lessons were worthy of being passed on to the young folks of today, who are the country’s future," he said.

To forget these men and women’s hardships is to forget American history. How can you fight when everyone thinks you’re incapable of fighting? How can the places you’re stationed in be more hospitable than your own home? How can you serve a country that won’t serve you?

In Tuskegee, “they would constantly use the N-word, and you couldn’t respond in a way that everyone nowadays would respond,” says Cheo Hodari Coker, the grandson of Lt. Col. Bertram W. Wilson, who was a part of the 100th Fighter Squadron in the 332nd Fighter Group and died in 2002. “You’re in the Deep South. There are instances of Black soldiers being lynched for wearing their uniforms and medals. At Tuskegee, there were German POWs and they had to give up their seats for the German POWs because they were white.”

Coker himself is a storyteller. The creator of Netflix’s “Luke Cage” and a co-writer of “Creed II,” Coker understands the importance of telling these stories specifically to the youths.

“I think sometimes we take advantage of the importance of helping kids dream.” he says.

His grandfather directly influenced his work on “Luke Cage,” Coker says: “When I pitched ‘Luke Cage,’ I talked about what it’s like to live around a hero and I talked about my granddad. Imagine if Batman was your granddad.”

Having such role models at an early age inspires youths to want to do great things.

“He made it his mission to integrate the Air Force,” Melville says of his great-uncle. “He looked at this as, ‘How can I use the system to diffuse the system?’"

“The example my grandfather set is the example that I follow,” Coker says. “Him doing that gives me confidence every single time I have a little bit of doubt. I look at pictures of him in his cockpit and think, ‘You know what? This is nothing compared to what he went through.’"

Kaleb Anderson, 17, a senior at Benjamin Banneker Academic High School in Washington, D.C., is enrolled in the Urban Journalism Workshop, a program of the National Association of Black Journalists. He plans to pursue a career in broadcast journalism.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Tuskegee Airmen: WWII Black aviators get Lucasfilm treatment