Impeachment: even the Senate's oath is controversial in hyperpartisan age

At 2.08pm on Thursday, a pair of pages opened the filigreed doors of the Senate. A quartet of senators – two Republicans and two Democrats – escorted the US supreme court’s chief justice, John Roberts, dressed in a long black robe, into the chamber. So began the Senate impeachment trial of Donald Trump.

Chuck Grassley, the Senate’s president pro tempore (for the time being), instructed Roberts, who will preside over the trial, to raise his right hand and place his left hand on the Bible to be sworn in.

“Do you solemnly swear that in all things appertaining to the trial of the impeachment of Donald John Trump, now pending, you will do impartial justice according to the constitution and laws: so help you God?” Grassley said, reading from an antiquated script.

Roberts swore that he would. He then turned to administer the same oath to every senator in the chamber. Owing to one absence, 99 right hands rose in the air. When Roberts finished, the senators responded in unison: “I do.”

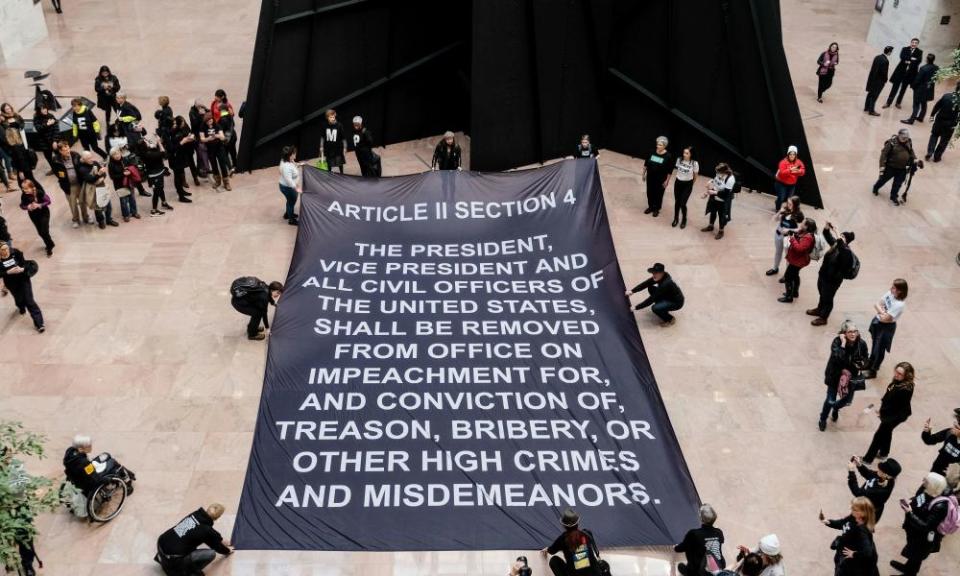

A new age of political tribalism and partisan warfare will test the resonance – and relevance – of that 232-year-old pledge that set in motion the next phase of a deeply divisive effort to remove the president from office during a presidential election year.

The Senate majority leader, Mitch McConnell, vowed to overcome the cynicism and bitterness that has seeped into every aspect of American political life, gravely compromising the Senate’s longstanding claim to be the “greatest deliberative body in the world”.

“This chamber exists precisely so that we can look past daily dramas and understand how our actions will reverberate for generations,” he said, before the ceremonial swearing-in. “So that we can put aside animal reflexes and animosities, and coolly consider how to best serve our country.”

But few of the president’s adversaries will find comfort in McConnell’s words.

“I’m not impartial about this at all,” the majority leader declared last month, arguing that impeachment is an inherently political process. As such, he had worked in “total coordination” with the White House over impeachment, he said, an approach that has made even some Republican senators uncomfortable.

The comments ignited a firestorm. Democrats said it was proof that for McConnell and the entire Republican caucus, the oath they swore would be nothing more than empty words. Republicans wondered how the Democrats could claim impartiality after three years of denouncing the president and his policies, not to mention that four senators who took the oath are running to replace him in November.

“.@SenSanders, @SenWarren, @SenAmyKlobuchar, and @SenatorBennet are spending millions of dollars to defeat @realDonaldTrump, and we’re supposed to believe they will be impartial during the trial?” Senator Marsha Blackburn, a Tennessee Republican, wrote in a tweet shared by the president. “They should recuse themselves.”

The senators – Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Amy Klobuchar and Michael Bennet – have all said they believe the evidence is strong enough to convict the president and remove him from office.

Before she quit the presidential race, Senator Kamala Harris of California was asked about her support for removing Trump from office. Was that fair to the president?

“It’s just being observant,” said Harris, a former California attorney general. “Because he has committed crimes in plain sight.”

Likewise, the South Carolina senator Lindsey Graham has said he would “do everything I can” to make impeachment “die quickly”.

“I am trying to give a pretty clear signal I have made up my mind,” he said during an interview with CNN at the Doha Forum in Qatar last month. “I’m not trying to pretend to be a fair juror here.”

“We’re going to reach a verdict and the verdict is going to be acquittal,” the Texas senator Ted Cruz said in an interview on Fox News. “The verdict is going to be not guilty.”

Fairness, it would seem, is in the eye of the beholder.

There remains a flicker of hope that at least one critical element of the trial might be bipartisan: the thorny decision of whether to summon new witnesses and documents.

For weeks, the chambers were at an impasse over precisely how and when to proceed to the trial stage of the impeachment inquiry. After a month-long delay, the House speaker, Nancy Pelosi, relented and on Wednesday the chamber voted to send two articles of impeachment to the Senate.

“Time,” she declared, “has been our friend.”

As the House signed and delivered articles, new details were emerging about Trump’s alleged effort to extract a political favor from Ukraine, which is at the heart of his impeachment trial. Troves of documents and interviews from Lev Parnas, an associate of the president’s personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, offered fresh insight into the alleged pressure campaign and Trump’s involvement.

Related: Who is Lev Parnas? Soviet-born operator thrust into Trump impeachment scandal

And just hours before proceedings got under way on Thursday, a non-partisan federal watchdog agency concluded that the Trump administration had violated the law by withholding congressionally approved military assistance to Ukraine, another matter at the heart of the case against the president. Democrats said the report strengthened their argument to allow new documents and evidence during the Senate trial.

A small but influential contingent of Republican senators have said they would like to hear from witnesses, particularly John Bolton, the former White House national security adviser who was present for many key episodes covered by the House’s inquiry. Democrats only need four Republicans to force a vote on whether to subpoena a witness.

But their effort to “do impartial justice” faces a new obstacle. The Kentucky senator Rand Paul has vowed political retribution for displays of disloyalty. If any Republican lawmaker helped Democrats call a witness they hoped to hear from, Paul said he would force a retaliatory vote on a controversial witness the senators hoped to avoid.

At the top of the list is Hunter Biden, son of the Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, who served on the board of a Ukrainian gas company and is at the center of a corruption conspiracy theory promoted by Republicans, and the whistleblower whose complaint launched the impeachment inquiry.

“If you vote against Hunter Biden, you’re voting to lose your election, basically,” Paul told Politico this week.

Opening the door to witnesses could disrupt McConnell’s carefully laid plans for the Senate trial that he intended to have “only one outcome”.

“The weight of history sits on [our] shoulders,” Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader, said after the swearing-in ceremony concluded, “and produces, sometimes, results you never know will happen.”