Impeachment Is Not a Fair Fight, and on Day One It Showed

If it looked like House Republicans were throwing a lot of mud at the wall to see what might stick during the first day of public impeachment hearings, that’s because they had settled into a strategy many defense attorneys adopt when the prosecution has the goods on their client—confuse the issues and distract the audience from the evidence at hand.

I’ve tried many federal criminal cases, and Wednesday’s hearing looked a lot like trials in which the prosecution has the defendant on tape admitting to a crime. When defense attorneys can’t mount a defense on the merits, they raise a lot of peripheral issues in the hope of convincing at least one juror that there is reasonable doubt.

So every time you heard the Republican’s designated counsel ask about Hunter Biden’s language skills or one of the Republican members of the Intelligence Committee ask whether the Obama administration sold Javelin missiles to Ukraine, what you were actually hearing was a defense attorney doing his level best to avoid talking about what his client said on tape. It was chaotic and often unfocused, though not always. In fact, there were moments when members actually executed their playbook with some skill.

But they simply can’t overcome the abundant evidence Democrats possess to prove their central point—that President Donald Trump conditioned military aid to Ukraine on a public announcement that his political rival, Joe Biden, was under investigation.

When prosecutors have overwhelming evidence, as the Democrats have here, it can be tempting to pile on as much evidence as possible. But when too many points are made, the jury has difficulty picking out what is important. It’s better to select a few key points and hammer them over and over.

That’s what Democrats did effectively at the first hearing. They made the most of a rule that permitted an attorney for each side to conduct 45 minutes of uninterrupted questioning. Experienced trial lawyers are better at asking questions than politicians, and it takes time to develop a strong line of questioning, and Democrats chose well turning to an experienced former federal prosecutor who has handled many high-profile cases involving organized crime.

Daniel Goldman observed a cardinal rule for trial attorneys: Let your own witnesses shine. He served up softballs for Taylor and let his testimony—not Goldman’s questions—be the focus. Twitter was agog at his performance, as if he had put on some kind of master class. Actually, I thought the virtue of his performance was how basic it was. Only once did he call attention to himself with a very dry line about wanting to spend a little time reading from the transcript, “as we’ve been encouraged to do.”

But make no mistake about it—Goldman had an easy job. William Taylor, the State Department’s top diplomat in Ukraine, and George Kent, the State Department’s top expert on Ukraine, made for exceptional witnesses. Both men have long records of service under Republican and Democratic administrations. Taylor, slightly older, has the added distinction of being a West Point grad and Bronze Star recipient in Vietnam. Over several hours of testimony Wednesday, they came across as credible, even-tempered and nonpartisan.

Many commentators have bashed the performance of Republican attorney Steve Castor, openly predicting that he will be mocked on the upcoming edition of “Saturday Night Live.” Certainly his lack of experience trying cases showed. His opening line of questions, which attempted unsuccessfully to get Taylor and Kent to agree to a confusing conspiracy theory about Ukrainian interference in the 2016 election, was particularly choppy. But Castor had very little to work with, and unlike an attorney at a trial, Castor wasn’t allowed to just ask a few questions and sit down. It appeared that he was told he had to fill 45 minutes, which is not easy to do when your side has no legitimate defense on the merits. He tried his best to testify through his questioning and confuse the issues—he spent a lot of time trying to get Taylor to acknowledge that Rudy Giuliani’s “irregular” diplomatic channel wasn’t as irregular as it could have been—but he could have sharpened his questions considerably.

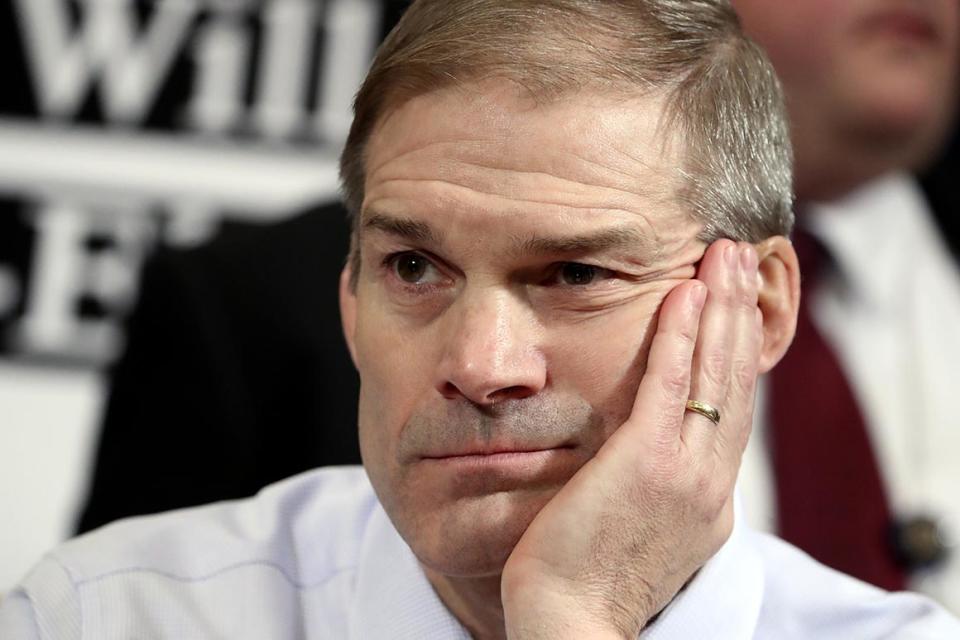

Castor did a much better job, however, than prominent Trump allies Reps. Jim Jordan and John Ratcliffe. Both men appeared to be trying too hard to create a “gotcha” moment, with Jordan in particular speaking at light speed, as if he were trying to squeeze in 15 minutes of content into five minutes of questioning. He would be better off trying to make four minutes worth of arguments in five minutes, by speaking slowly and developing one or two key points.

The best performances on the Republican side came from less flashy members of Congress like Elise Stefanik and Brad Wenstrup, who made some legitimate points, such as Wenstrup’s questioning that focused on the lack of direct interaction between Trump and the two witnesses. While this argument has limited long-term value—witnesses who interacted with Trump will testify later—it is a reasonable point and it landed solidly.

Going forward, you can expect more of the same from Republicans, although they would be smart to whittle down the number of irrelevant issues they raise and focus on a few points. Unlike a real life trial, viewers don’t have to pay attention and might change the channel after a few minutes, so repeating your best points makes a lot of sense.

What hamstrings Republicans most is the psychology of Trump himself. He has refused to admit the quid pro quo and instead argue that it is not an impeachable offense, as many prominent Republicans have advocated. Admitting wrongdoing would take a lot of the air out of the impeachment hearings, but Trump appears incapable of doing so.

So Democrats will remain in the enviable position of proving a point on which they have ample evidence, even though Trump has kept them from getting key documents and witnesses. It’s not hard to tell a compelling story when you hold all the cards, but it won’t be a winning hand unless they can move public opinion.