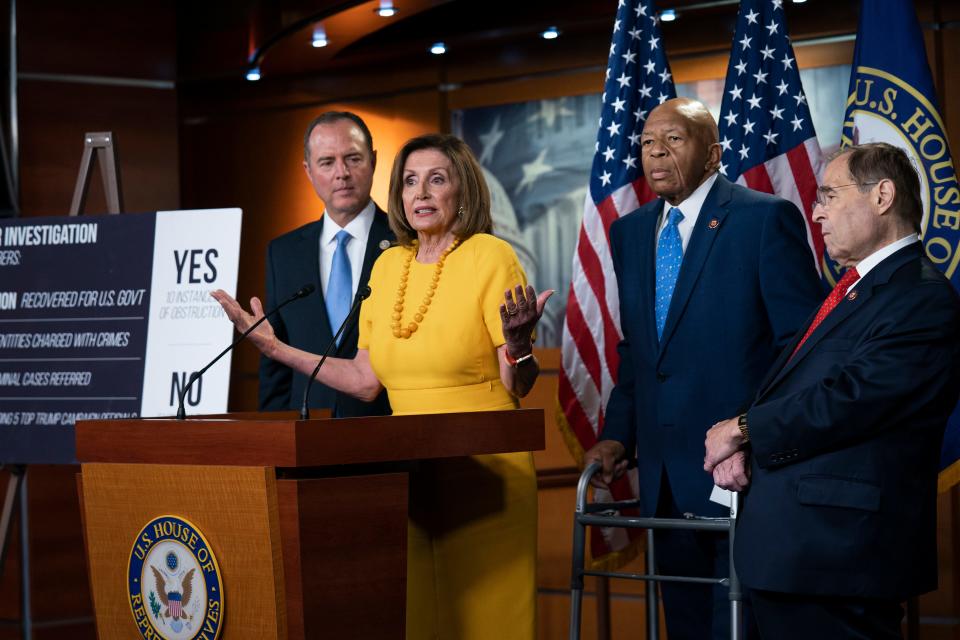

Impeachment: Trump obstruction is unprecedented. Congress has power to compel testimony

If you read the U.S. Constitution and look for the words “oversight” and “investigation” in Article I, which defines the powers of Congress, you will not find them. Neither do they appear in the Bill of Rights. The terms also do not appear in Article I Section 8, popularly known as the “elastic” or “necessary and proper clause,” although that is usually cited as the source of those powers. The framers of the Constitution simply believed them to be inherent in the job description of a legislature. Oversee the executive and investigate wrongdoing is what the British Parliament did as far back as the 17th Century when it was known as “the grand inquest of the nation.” Congress, they believed, should do no less. It was understood from the very beginning that Congress wielded these powers and it is only now that this power is being willfully and maliciously obstructed by the president and his congressional allies.

Congress' history of investigation

When Robert Morris, who served as superintendent of finance — the precursor to Secretary of the Treasury, came under attack for how he spent the funds appropriated by the Continental Congress, he sought to clear his name by asking Congress to investigate his expenditures. It is probably the only time in history that an official demanded to be investigated by Congress.

Don't stall: The time for waiting is over. The House must move on Trump impeachment articles now.

The first investigation of possible wrongdoing under the Constitution took place in 1791 in the aftermath of the defeat of an American army under the leadership of General Arthur St. Clair in which more than 600 American soldiers were slain by Indians. Such was the prestige of George Washington that it was suggested he lead the probe into the humiliating defeat. A congressman from Virginia introduced a resolution to that effect, but so concerned were these early legislators that the executive branch not be given the responsibility of investigating itself, that the resolution was amended to turn the investigation over to a select committee of the House. From that early probe flowed the countless investigations undertaken by Congress, some of which illuminated corruption and misconduct and others were partisan hatchet jobs. But never was the power of Congress to conduct these investigations successfully challenged as being, somehow, illegitimate.

Stonewalling was not tolerated

As early as 1795, Congress exercised its powers to deal with hostile witnesses when reports surfaced that members of Congress had been offered bribes by a land speculator. Congress employed the power to compel the attendance of reluctant witnesses through the use of its subpoena power. It also held a witness in contempt of Congress and had him arrested by the sergeant-at-arms of the House. By the second decade of the 19th century, the issuance of subpoenas by Congress became commonplace events. But by the 1850s members of Congress became uncomfortable as jailers of recalcitrant witnesses and began the practice of turning over those cited for contempt to the Justice Department. That 19th century Congress could not have foreseen a Justice Department joined at the hip with the White House and acting as its defense team, or they might have considered keeping open the congressional jail.

The solution is plain: If Trump is impeached, Senate Republicans should simply vote to dismiss the case.

Congress, shorn of its power to compel witnesses to testify under threat of a subpoena and to hold them in contempt and subject to some kind sanction such as a monetary fine, leaves Congress as a toothless debating society. Blocking a witness from testifying, such as took place last week when Ambassador Gordon Sondland was forbidden to testify before the House Intelligence Committee, and vowing not to cooperate in the future with the committee, subverts the venerable principle of checks a balances. Presidents have often been nettled by congressional committees but no president has ever successfully challenged the right of committees to take testimony from witnesses thereby obstructing their ability to function as the framers intended.

This act of subversion by President Donald Trump is not merely riding roughshod over some informal norm that governs the way that business is customarily conducted. It is a frontal attack on a time-honored power of a legislative body handed down to us from centuries of British lawmakers struggling to curb the arbitrary power of kings and the legislatures of our own country exposing official wrongdoing, ineptitude and stupidity.

Much is made of the the phrase “rule of law” by those rightly opposed to the violation of our immigration laws, but it is a far graver transgression of the rule of law to undermine the foundational principle of the republic that each institution of our national government has the requisite weapons to ward off the incursions and excesses of the other two.

Ross K. Baker is a distinguished professor of political science at Rutgers University and a member of USA TODAY's Board of Contributors. Follow him on Twitter: @Rosbake1

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Impeachment: Trump can't keep stalling. Congress CAN compel testimony.