What is an implosion, and what would it have been like for the Titanic sub-passengers?

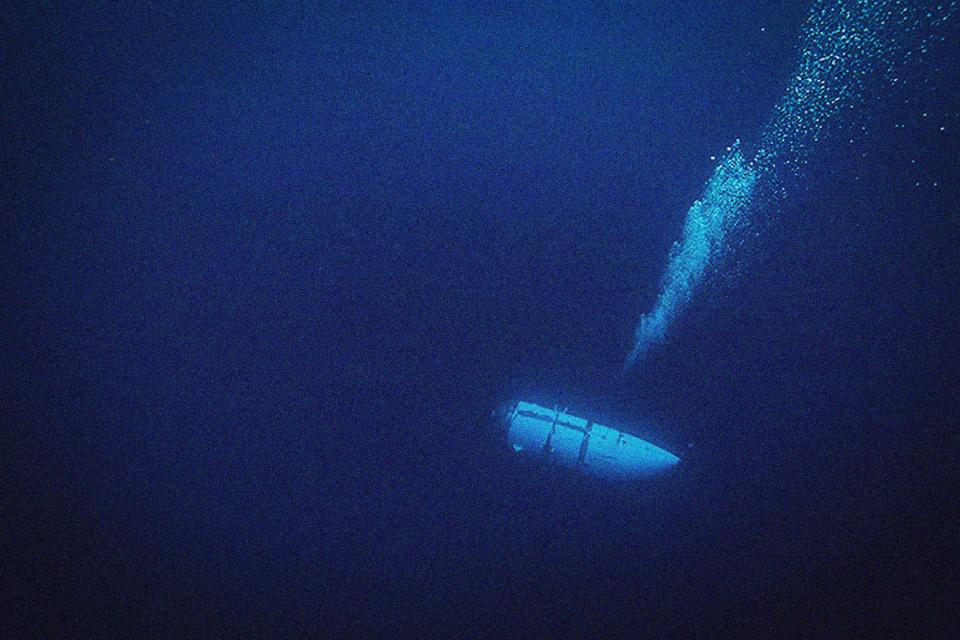

For days, the world could only imagine the grim scene: five men cramped in a cold, dark tube, knowing that they were about to run out of air. In reality, those aboard the Titan submersible most likely died instantaneously in what officials called a “catastrophic implosion.”

The deep-sea water pressure that appears to have crushed the 22-foot craft would have been roughly equivalent in weight to the 10,000-ton, wrought-iron Eiffel Tower, experts told NBC News on Friday. The colossal forces would have acted so quickly that it would be like the vehicle’s carbon-fiber hull “suddenly vanishing” before anyone inside knew what was happening, one expert said.

“They would have known nothing — the minute this body of water hit them, they would have been dead,” said Paul White, a professor at England’s University of Southampton, who specializes in underwater acoustics and forces.

With the vast search effort now over, the focus turns to the many unanswered questions that remain.

Though the tourist sub lost contact around 1 hour 45 minutes into its 2-hour dive, and was found on the seabed around 1,600 feet from the Titanic’s bow, officials don’t yet appear to know exactly where or why the tourist sub imploded.

A U.S. Navy analysis of acoustic data “detected an anomaly consistent with an implosion or explosion” near the Titan around the time it lost communications Sunday, a senior Navy official said. The sound was not definitive, but it was immediately shared with commanders, who decided to keep searching, the official said.

The violent nature of the implosion, and at such extreme depths, makes any attempt at recovering the vessel and its passengers even more problematic.

“There would be substantial challenges with recovering any bodies,” said Dr. Nicolai Roterman, a deep-sea ecologist at the University of Portsmouth, in England. “And I think the priority at this point may well be focusing on recovering the debris as much as possible.”

In a news conference Thursday, the Coast Guard declined to answer specific questions about recovering efforts. “I don’t have an answer for prospects at this time,” Coast Guard Rear Adm. John Mauger told reporters.

Titan’s abrupt demise was apparently caused by the same deep-sea forces that make expeditions like it so rare. It’s why fewer people have been to Titanic ocean depths than have been to space.

Anyone who has dove to the bottom of a pool has noticed the difference in water pressure, a heaviness in the nose and ears. “Imagine that — but 1,000 times more,” White said. “That’s what it’s like at these depths. It’s a phenomenal force.”

At Titanic depths, some 12,500 feet down, the water pressure is nearly 400 times more than at the ocean’s surface — some 6,000 pounds would have been pressing down on every square inch of Titan’s exterior.

“If you translate that to a physical force, it’s going to be in the order of high thousands of tons to 10,000 tons, so the analogy would be the weight of the Eiffel Tower being the kinds of loads it’s experiencing,” said Blair Thornton, a professor of marine autonomy, also at the University of Southampton, who has designed and built dozens of robot-operated deep-sea submersibles.

Roterman, at the University of Portsmouth, agreed with the Eiffel Tower analogy.

His work has taken him to near Titanic depths in the Indian Ocean, descending to observe geothermal hot springs at around 11,400 feet in the Japanese submersible, Shinkai 6500. Unlike Titan, Shinkai is owned and operated by the Japanese government, and has been rigorously testing throughout its 1,500-odd missions.

Experts and former passengers have questioned the testing regime and safety record of Titan, which had completed about 20 dives.

OceanGate Expeditions, the company that owned and operated Titan, has not responded to those criticisms this week. It did not return NBC News’s request for comment. But in promotional information released before the accident, it said the “state-of-the-art vessel” had been designed in collaboration with NASA and Boeing, undergoing what it described as “incremental testing” for safety.

Like many submersibles, the Shinkai 6500 seats its crew in a titanium sphere, whose manufacture ensures less than 1-millimeter of deviation in its curvature. By contrast, the Titan’s experimental design included a carbon-fiber hull and only the ends of the vessel were made from titanium — a departure from the standard practice.

Though he has no direct knowledge of Titan’s design or construction, or what contributed to its failure, Thornton, the Southampton professor, said catastrophic incidents can be the result of minute “defects” in manufacturing.

“And when I say defects, I don’t mean any kind of negligent defects — just that when you make things there are small, microscopic defects,” he said, adding that this was the only implosion he was aware of involving a manned submersible.

When these defects are exposed to huge forces, they can cause deformations in the structure, leading to higher stresses around those areas, Thornton explained.

“The air inside would compress down to a point, and the forces of the water rushing in and the collapse would be enormous,” he said. “Structurally,” he added, it would be equivalent of the capsule housing the crew “suddenly vanishing.”

“This whole process from start to finish is happening in the blink of an eyelid, the click of a finger,” he said. “I don’t think there would have been any suffering or any knowledge of what happened.”

This article first appeared on NBCNews.com.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com