In one Texas city where refugees are welcomed, immigration ban sows fear and confusion

AMARILLO, Texas — Evelyn Lyles has been retired for four years, but she’s never worked harder. Up before dawn, she tries to leave her house most days around 7 a.m., driving her old Toyota Corolla across town to the Astoria Park Apartments, where she spends most of the daylight hours checking in on the people she lovingly refers to as her “family.”

They are refugees from all over the world who have landed in this remote town in the sweeping plains of the Texas panhandle seeking to forge a new life from the often chaotic one they left behind: men and women and children from far-flung places that Lyles has never seen, such as Burma, Somalia and Iraq. She is not the first face they see when they step off the plane in Amarillo, but weeks later, when resettlement agencies leave them to adapt to life in a new land on their own, Miss Evelyn, as the 65-year-old retired schoolteacher is known, becomes their most important friend.

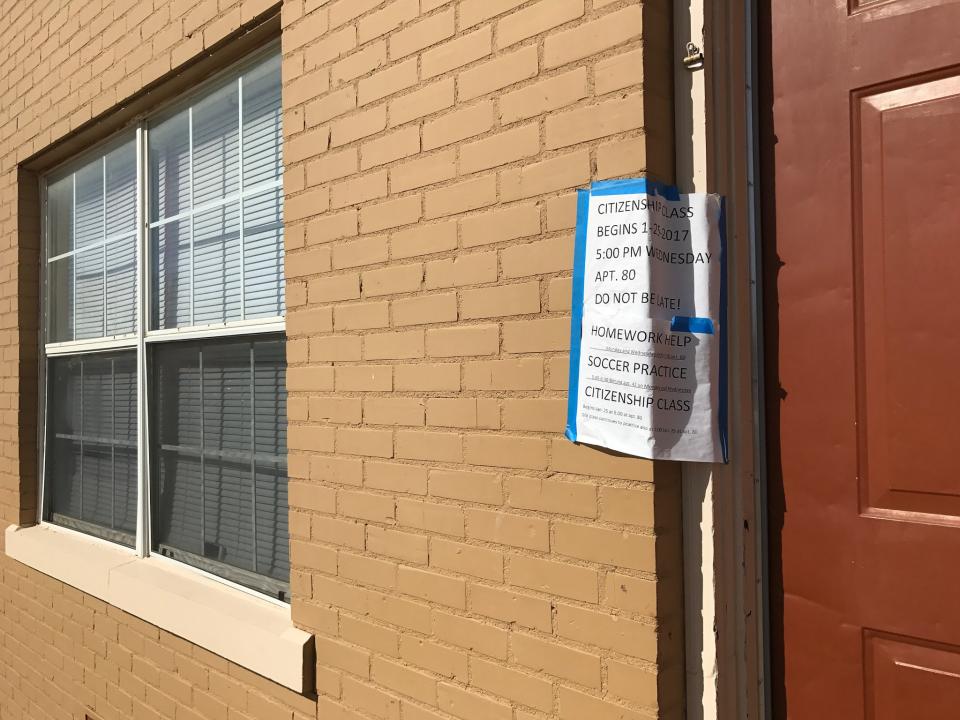

Along with helping them practice English and learn their way around a foreign land, Lyles assists scores of families with little, but consequential, things like making doctor’s appointments and filling out job applications. She teaches mothers who have never used a stove how to bake birthday cakes, and she helps the kids with their math and vocabulary words. She tutors families about American history and culture as they pursue citizenship. She helps them with the overwhelming task of starting over.

“If you see a need, in my eyes, you should step up and fill it, and that’s what I am doing,” Lyles explained during a rare break between appointments a few days ago. “God expects us to reach out to our neighbors, whether they are our color or not.” Besides, she added, “unless you are an American Indian, we are all descendants of someone who came here. All of us. …We were all refugees at some point.”

Lyles is a shepherd for refugees in what would seem to be an unlikely place. Amarillo is firmly Donald Trump country, an unwavering bastion of bright red in a safely Republican state known for its anti-immigrant politicians. Yet for the last several years, Texas has led the country in refugee resettlement. Roughly 7,800 arrived in the state alone last year, many landing in big cities like Dallas, Houston and Austin, according to State Department data. Amarillo has become the state’s leading safe haven, accepting nearly 400 refugees alone in 2016 — the most per capita of any city in Texas.

Last year, as Trump regularly railed against refugees as a potential terrorism risk, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott announced that the state would no longer play the middleman in helping the federal government dole out money to local resettlement agencies, arguing that refugees were a potential “security threat” to the state — a symbolic but largely meaningless maneuver that did not stop the flow of new immigrants.

Even amid the incendiary rhetoric often aimed at refugees, Amarillo’s new arrivals have generated little public outrage. They have been largely greeted with open arms by local officials, community groups and dozens of churches in town that have made it their ministry to help the refugees build new lives in America. But that mission has been upended in recent days after President Trump’s Jan. 27 executive order aimed at slowing the flow of foreigners entering the United States.

The most controversial part of the order, which blocked arrivals from seven Muslim-majority countries for 90 days and indefinitely blocked Syrian refugees, has been temporarily suspended amid federal court challenges. But the other parts of the order remain intact, including Trump’s decision to reduce the number of resettlements this year to 50,000 from the 110,000 that originally had been planned.

The order has already had an impact on Amarillo, forcing six people who had been en route to the city after years of vetting to turn around. And many dozens more who had been scheduled to arrive in coming weeks are now in limbo. That includes the husband of a young mother from Burma who arrived with her 18-month-old son in Amarillo on Jan. 26. After years of background checks and interviews, the mother and son were the last family to arrive before Trump’s order took effect. Her husband had been scheduled to follow in coming weeks, but now, it’s unsure when or if the family members will ever be reunited.

“It’s heartbreaking,” said Natalie Lowe, an area director with the Refugee Services of Texas, one of two nonprofit resettlement groups that work with refugees coming into Amarillo and have been assisting that family and many others. “These people have been waiting and suffering for years. They have been vetted and screened more strongly than any other traveler that comes into this country, and now, just as they were on the brink of finally getting here, they are pushed into the unknown.”

Trump’s move has caused handwringing among people here who voted for him and generally support his efforts to keep the country safe but are vexed by his approach to refugees. As in other cities, many of the people working here to help resettle refugees are affiliated with churches and other religious groups that see helping refugees as a key part of their ministry. A local pastor, who declined to be named because he didn’t want to get publicly caught up in the controversy, said he and others in his congregation were stunned and upset by Trump’s move, which he described as “not what Jesus would do.” “Let’s have strict security, but to turn away people who have been screened, who have been persecuted and need our help, it doesn’t feel right,” the pastor said.

Lyles, who perhaps understands more than anyone here what refugees have gone through in order to claim a new life in this country, did not vote for Trump but says she supports him now as her duty as an American. She has tried to avoid the political debate over refugees, but she admitted that the new president’s actions have made it hard. “He’s really diligent right now, trying to worry about terrorism or somebody that’s coming in that’s got a radical viewpoint. … He’s trying to be protective of our country, and after all, (people) did vote for him for that reason,” Lyles said, speaking carefully, like the special-education teacher and diagnostician she used to be.

But she suggested that Trump didn’t fully understand the issue and had gone too far. She dismissed his criticism that the refugees hadn’t been properly screened, pointing to a family she knew that had undergone screening for more than five years before they were allowed into the country. She said none of the people she has worked with in the 14 years she has been volunteering with refugees in Amarillo have been “unsafe.” And she worried about the policy’s impact on not only America’s reputation as a welcoming country but also on Amarillo, a town she said has been deeply enriched by its new diversity.

“We call America the melting pot (because we) welcomed all these different cultures, and it’s enriched our country,” Lyles said. “I never saw anywhere where it says we are suddenly going to stop immigration at the year 2017. … That’s not who we are.”

Even to those who live here, Amarillo’s role in accepting refugees is an unexpected one. With a population of roughly 196,000, the town is so remote from other parts of Texas (Dallas is a six-hour drive; Austin is7 1/2) that residents here have long mused about Amarillo and other panhandle cities seceding to form their own state. It’s a town that remains defined by its rich history as a cattle town. Cattle feedlots dot the landscape on the roads leading into town, supplying meatpacking plants that are the region’s biggest employers and provide roughly a quarter of the nation’s beef.

But it’s the other legacy that many don’t know about. Amarillo, named for the yellow wildflowers that dot the wide-open prairie here in the springtime, has had a long history of opening its doors to refugees — dating back to 1975 when Vietnamese relocated here after the end of the Vietnam War. Over the years, waves of immigrants from more than a dozen other countries have come to join them — among them, residents of Iran, Iraq, Congo and Ethiopia in the past year alone.

On historic Route 66, which cuts through the center of town, the old roadside motels with their classic cowboy signs now are mixed with once-empty buildings that have been newly occupied by Somali restaurants and specialty stores catering to the many ethnicities that now call Amarillo home. Taco joints run by Mexican immigrants sit alongside Middle Eastern restaurants, south Asian supermarkets and the last of the old honky-tonks that once provided brief escape to those passing through on old Route 66.

The transformation has been more dramatic in other nearby cities. In tiny Cactus, Texas, a town of about 3,000 an hour north of Amarillo, an estimated 25 percent of the population is said to be made up of new immigrants. Largely from Somalia and Burma, they moved there to work at JBS Swift, one of the largest meat processing plants in the country.

The plant was nearly shut down in 2007 when Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents raided the plant and arrested hundreds of illegal immigrant workers, deporting them back to Mexico and parts of Central America. Since then, the plant has relied heavily on newly arrived refugees as its workforce, including hundreds who live in Amarillo and commute by bus two hours a day back and forth for their shifts.

“Most Americans don’t want to work at a meatpacking plant,” Lowe said. “So that’s been one of the biggest draws. People can come here, take care of their family and make a life for themselves.”

In Cactus, which has grown up around the plant, there are signs of the changing population. The town, which was blown away by a tornado a few weeks after the immigration raid in 2007, has been rebuilt to include a new mosque. On the main strip is a new Somali-American community center — an outpost of a large group based in Amarillo. On a recent afternoon, men in loose, flowing shirts and skullcaps could be seen walking down the dusty streets here alongside Hispanic men in cowboy hats — co-workers leaving their daily shift at the plant.

Many in and outside the city became aware of Amarillo’s relationship with refugees last year when a handful of conservative websites, including Breitbart and Watchdog.org, published posts saying the city was being overrun by refugees who were building “Muslim ghettos.” Amarillo Mayor Paul Harpole, a Republican, was quoted complaining about the impact of refugees on schools and other city services. He said that Amarillo wasn’t equipped to handle the influx and that immigrants were so ill-served that they were forming their own informal governments — though he later told reporters he had been misquoted. The stories went viral on other conservative blogs. “Sharia law! This is how it begins!” one wrote.

But Harpole’s comments opened a dialogue with resettlement groups who agreed to curb the number of arriving immigrants by declaring Amarillo to be a “reunification city” — meaning that people can only come here if they already have a family member established here. But that hasn’t solved all the problems, according to the mayor, including some schools that continue to be taxed by kids who arrive speaking little to no English. Harpole has said the city has struggled to keep up with the estimated 45 different languages now spoken in the city — a challenge for 911 operators who sometimes can’t communicate with callers because of the language barrier.

Still, Harpole, who did not respond to a request for comment, has repeatedly insisted he doesn’t have a problem with refugees — as long as the city can take care of them. In an interview with the Amarillo Globe-News last week, the mayor broke with his party and criticized Trump’s immigration order for stopping people who had already been vetted and for treating refugees too broadly. He pointed out that refugees in Amarillo aren’t responsible for an uptick in crime but rather just want to find jobs and “fit in” to America.

“I have a problem with stopping them cold when they’ve been vetted and painting them all with the same brush,” Harpole told the paper.

Trump’s immigration order has only stoked fear among immigrants who were already suspicious of the New York billionaire and his attitude toward refugees long before his stunning victory in November. Even among those who are legally here in Amarillo on visas and green cards, there have been worries that they could be rounded up and deported. Others worry about not being allowed back into the country if they leave, meaning they may have to postpone or cancel visits to see relatives abroad.

“Even before this happened, people were saying: Don’t do anything to call attention to yourself, drive below the speed limit, stay low-key,” said Van Lian, 28, who came to Amarillo as a refugee from Burma six years ago. “A lot of people are really scared.”

Lian, who is currently applying to become a U.S. citizen, escaped with his family from Burma to Malaysia, where they spent five years scrambling to make ends meet, in a country where refugees aren’t permitted to work, while they waited for passage to the United States. They immigrated to Grand Rapids, Mich., spending just two days there before moving to Amarillo, where other relatives had settled. Other family members had been approved for entry after four years of rigorous screening and were set to join them in coming months. But, like others, they are now in limbo. “We don’t know what they will do,” he said.

After arriving in the U.S., Lian got his high school degree through the vocational training group Job Corps. He owns two businesses: a sushi restaurant and a tax preparation service, where he works to help other refugees. He shares space with Lyles in a donated three-bedroom apartment at Astoria Park that serves as a makeshift community center for immigrants. The two met when Lyles helped his family get settled in Amarillo.

“I love America so much. I have had so many opportunities here that I would have never had anywhere else,” he said.

Lyles stood nearby, a huge smile on her face. “He’s the American dream,” she said.

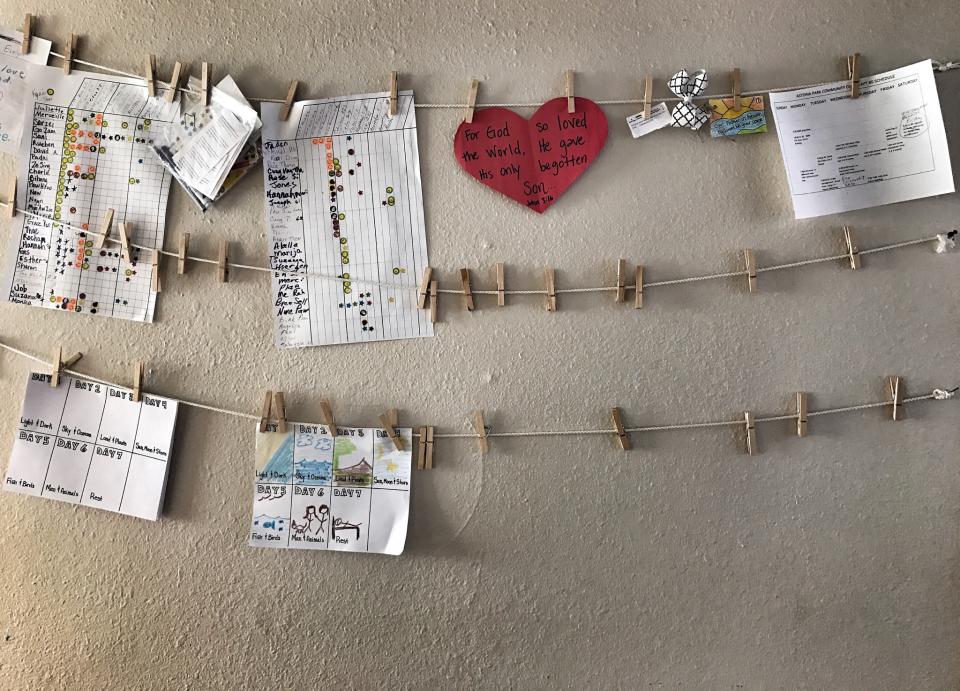

Walking through the apartment, which was mostly empty except for a few chairs and tiny tables, Lyles offered a quick tour of her community center, where refugees come for tutoring, citizenship classes and other life help. The owner of the complex loaned it to Lyles not long ago, after she spent years working out of the cramped rental office. Upstairs, there is a closet packed with guitars for a music class, which helps immigrants learn English through song. Downstairs, the wall is covered with tiny signs featuring vocabulary words and Bible verses, since Lyles, a proud member of the First Baptist Church, also views her job as a chance to minister.

In the kitchen, Lyles opened the oven to reveal a stack of paperwork — makeshift storage for space that is tight. “You make do,” she said. In a few hours, the place would be packed — kids downstairs on the hardwood floor for class, adults upstairs crammed into the tiny rooms for citizenship or language classes or anything else they need from Lyles.

They had all overcome so much to get there, to begin anew in a foreign land. And through them, in some ways, Lyles had been reborn too. She had started working with refugees in 2003 when, as a diagnostician at a nearby middle school, she noticed an influx of refugee kids and began working with them. On home visits, she met their parents, who asked her for help as they struggled to adapt to America. Soon, she was helping three families.

She loved the work and considered quitting her job to volunteer full time so she could help even more families, but then tragedy struck. In 2004, her youngest son, who had struggled with bipolar disorder, committed suicide. “I was suffering, and I needed something to fill that void,” Lyles said. “Those families became my friends. They became my family. All of them are my family.”

Even on this afternoon, where she is so busy she barely has time to escape to the bathroom, Lyles said she wouldn’t change anything. Her heart is with the refugee families of Amarillo, the ones she’s helped and the others she knows she will help in the future. She is quietly angry over how refugees have been portrayed and refuses to accept that Trump’s immigration order will be allowed to stand.

“My life, our lives, are so much richer with having them here. … They touch our lives, those of us who have always been in America. They touch our lives with their music, with their food, with their language, with their love for us. They love us,” Lyles said. “And it’s a two-way street. We love them. … We aren’t going to have a totally closed door. We just can’t.”

—–

Read more from Yahoo News:

Exclusive: Chuck Cooper emerges as likely choice for Solicitor General

President Trump announces full Cabinet roster