In wake of ICE raids, devastated communities and broken families

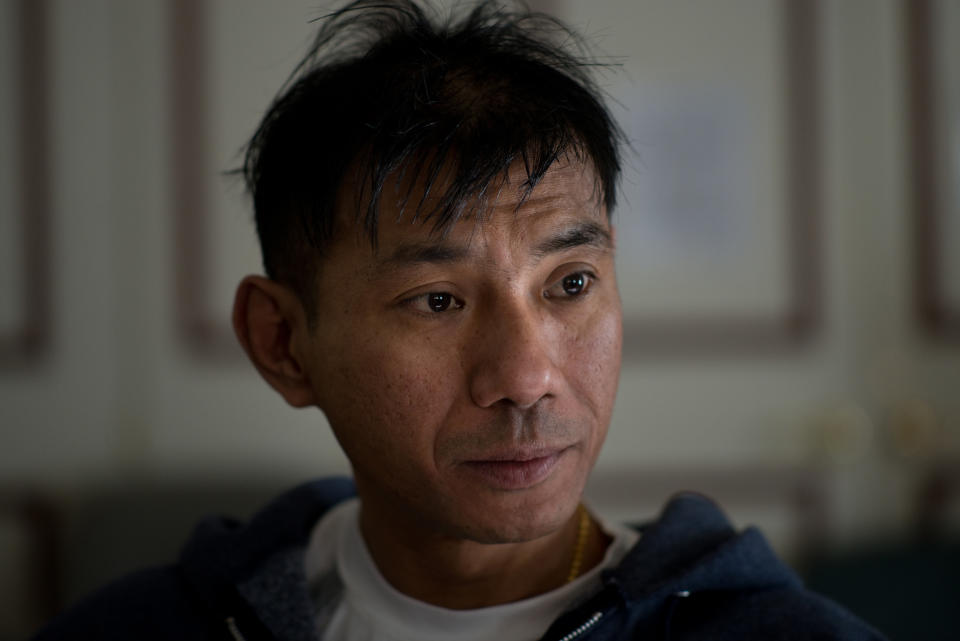

When Harry Pangemanan heard about the immigration raids on meat packing plants in Mississippi last week, it brought back memories of another raid, 13 years ago. Of hours spent hiding under a bed with his pregnant wife and toddler daughter, while Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents banged on doors, climbed through windows and took away three dozen of his neighbors in Avenel, N.J., in windowless vans.

The Mississippi raids may have been one of the most sweeping in ICE history, with 680 workers taken from seven plants around the state. But they were not the first. The Mississippi cities of Bay Springs, Canton, Morton and Sebastopol joined a long list of places — Postville, Mount Pleasant and Marshalltown, Iowa; Morristown, Tenn.; Hyrum, Utah; Greeley, Colo.; Grand Island, Neb., and Cactus, Texas — that are still dealing with the aftereffects of the sudden disappearance of workers, customers, taxpayers and parents.

“I watched the news and thought ‘it is happening again’,” says Pangemanan, who fled persecution in Indonesia to make a life in the U.S. He was not caught by ICE that morning in 2006, but his life was upended by the aftermath of the raid nonetheless. “I thought about the people. The children. The lessons they will now learn.”

The biggest ICE raid in history was in December 2006, when the Bush administration sent 1,000 ICE police, backed by local squads in riot gear, to six meatpacking plants in the Midwest and West owned by Swift & Co. Up to 20,000 workers were detained and nearly 1,300 were arrested on immigration charges. Families were torn apart, with fathers deported and American-born children left behind. The business, which struggled to find replacement workers even after raising wages to attract documented employees, was sold to a Brazilian company the following year.

In an article five years after that raid, the Salt Lake Tribune did an update on the town of Hyrum, and estimated that four out of 10 of those deported managed to return illegally, many living in even more precarious economic straits than they had before, because they could not find work. As for the six in 10 who didn’t come back, most represented a family torn apart.

That was also the case after a raid at a kosher meat plant in Postville, Iowa, on May 12, 2008, the largest single mass immigration arrest up to that time. Nearly 400 undocumented workers were arrested at the company, Agriprocessors.

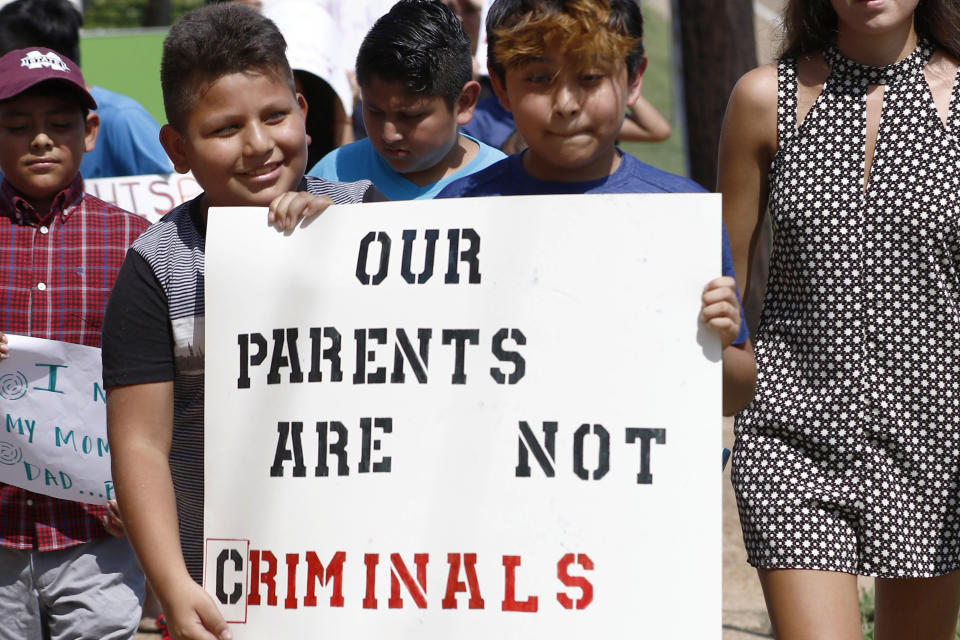

At the town’s only school, children ran to the windows as helicopters buzzed over the plant where their parents worked. Police cars blocked the roads in and out. Children sobbed in their teachers’ arms. Some parents of young children were allowed to return home with ankle bracelets, but others were not, and some youngsters came home to empty houses because both parents had been caught in the raid. When a refrigerated delivery truck with the word “ice” on the side came through a few days later, kids panicked and ran, thinking it was another raid.

Over the next few months, more than 1,000 people left Postville, 20 percent of the population. Some left because they’d been deported, others because they feared they might be. Nearly all returned to Guatemala. The Jewish population of Postville was shattered as well, because nearly all the Jewish adults in town worked in the plant. Although they were citizens, they too lost their jobs as the plant struggled to stay in business.

With so many people no longer paying rent, or shopping for groceries, or paying local taxes, the town’s economy weakened. Teachers were laid off as children moved away, and the school nearly closed.

Meanwhile, the owner of the plant was sentenced to 27 years in prison on 86 counts of financial fraud, a sentence that was commuted by Donald Trump in 2017. Some of those who were deported were allowed to return on U-Visas, granted to those who testify in criminal cases, because they served as witnesses in the trial of the plant’s owner.

Agriprocessors was sold and reopened under another name. Its workforce now includes some of those who returned on U visas and many Somali refugees, who replaced the ones who never came back.

It was the Postville raid that led to some of the only research on the question of the aftereffects of an immigration raid. Luther College and the University of Northern Iowa organized “The Postville Project: Documenting a Community in Transition.” Among the scientific papers on the site is one by a team from the UNI department of sociology. Titled “Postville: The Effects of an Immigration Raid,” it concludes: “After ICE agents leave town, people are incarcerated and families are split up; reporters also leave. Communities are left to deal with the aftermath, often with few resources. Research on the psychosocial effects of worksite raids is limited, though new findings show that children develop behavioral and mental health problems and people in the raided communities are susceptible to PTSD.”

Another study from that place and time found that even those not yet born during a raid can suffer consequences. In a paper in the International Journal of Epidemiology found that babies born to Latina mothers — both immigrants and American-born — in Iowa in the months after the raid were 24 percent more likely to have low birthweight than a control group born a year earlier. There was no such effect among children of non-Latina white mothers.

None of this surprises Pangemanan, who followed both these large raids, and countless smaller ones, from his home in New Jersey. His memories are vivid of the pre-dawn moment 13 years ago when, awakened by stomping, pounding and screaming in the garden apartment complex where he lived, along with other Indonesian-Christian immigrants fleeing persecution. They had all arrived on tourist visas that were issued by the Clinton administration as the fastest way to get these vulnerable people out of a dangerous place. Afraid to go home, they overstayed those visas, and missed the one-year deadline to apply for asylum that was put in place after they arrived. Final orders of deportation had been issued against nearly every adult male in the apartment complex by May 2006 when the ICE agents arrived.

The 35 men who were taken into custody that morning were soon deported to Jakarta. (Only men were targeted that morning because only men had self-reported to immigration in 2002, when the Bush administration compiled a database of immigrants from majority-Muslim countries. It was that list that eventually led to the deportation orders, even for men like these, who were Christian.)

Their children — about 70 of them, some born in Indonesia, some in the U.S. — have not seen their fathers in person since. All the children stayed, because those born in Indonesia faced anti-Christian discrimination at home (and were not yet on ICE’s radar), and because those who were American citizens were not allowed back permanently by the Indonesian government.

Most of the mothers took on two or three jobs to make up for their spouse’s lost income, and moved two and three families into a one- or two-bedroom apartment to save on rent. In addition, they found themselves sending money to Indonesia to help their husbands, who had returned with only the clothes they were wearing. All of the couples eventually divorced.

“I’ve cried with the kids whose parents made their divorces official, dissolved loving families,” says Pastor Seth Kaper-Dale of the Reformed Church of Highland Park, where many of the families sought shelter after the raid, because the children were afraid to sleep at home. “That’s the reality of facing a lifetime of separation.”

Pangemanan was not caught that day. He was arrested in 2009, when he was picked up by ICE agents waiting for him when he drove his daughter to school. He was jailed, then released pending investigation, and eventually took refuge with his family in Kaper-Dale’s church, living there for months until a court blocked his deportation while an ACLU lawsuit on his behalf is heard.

During those years he, his family and his church have cared for those left behind by the raid. He is a surrogate father to many of the children, most of whom are finishing high school and entering community college, he says.

As each subsequent raid, large and small, makes the news, he prays for those arrested and detained — as well as the ones left behind.

He had an intense reaction to the Mississippi raids, “I cried,” he says. “My first thought is about the children. Next, about the whole community. They will have very different lives.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: