Incentives game filled with wins and losses with long-term success rarely guaranteed

Win or lose, Oklahoma is playing a high stakes game as it looks to offer at least $700 million or more to win an electric vehicle battery factory that would employ thousands.

In making his pitch last week, Gov. Kevin Stitt declined to identify the company, though it is widely reported to be Panasonic with plans to supply electric vehicle batteries to new Tesla manufacturing in Texas.

“This is the largest factory investment in the state’s history and one of the largest in the country,” Stitt said. “This is one the most advanced and largest manufacturing facilities in the country.”

Other incentives are being weighed, as well, including a tax increment financing district in Pryor, where the operation likely will be based at the city’s sprawling Mid-America Industrial Park.

Stitt downplayed the risk of winning the operation, paying the incentives and then losing the plant before the full benefits are realized by the state.

“Companies don’t drop billions and billions of dollars on the most advanced manufacturing facility in the country and then pick up shop and leave in five or 10 years.”

History, however, tells a different story.

A history of bids, and setbacks

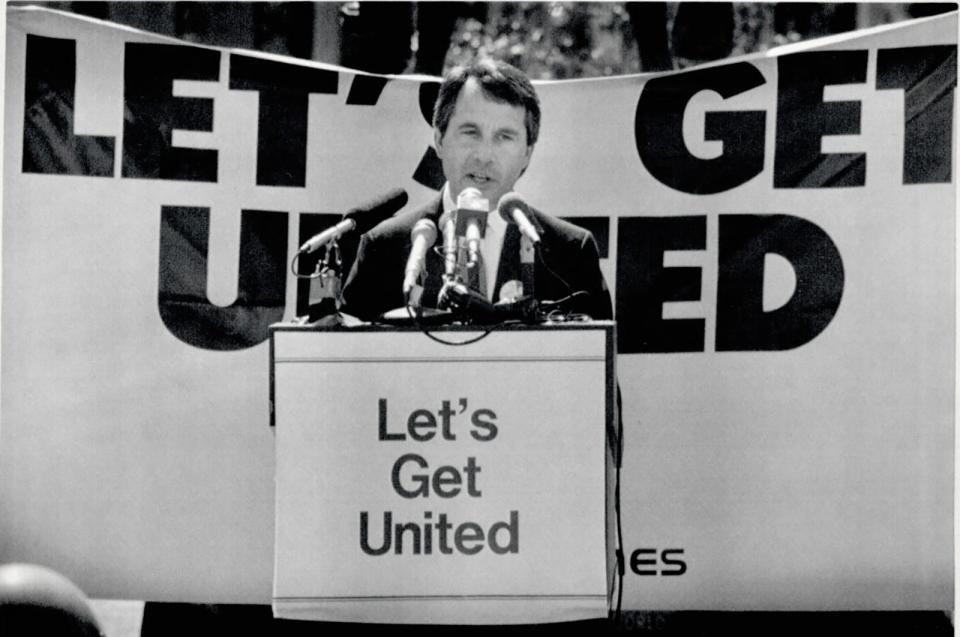

Thirty years ago, Oklahoma City competed in a nationwide bidding war for a United Airlines plant that was expected to employ 7,500 workers. Oklahoma City, still recovering from the 1980s oil bust, passed a 33-month temporary sales tax hike to offer $120 million for the plant.

Yet another $800 million in bonds was to be issued by the Oklahoma City Airport Trust to secure huge hangars, equipment and improvements. The city’s water trust pledged to chip in another $5 million, while $10 million was pledged by a financially challenged state Legislature and $2 million was pledged by Oklahoma County.

The bid was considered one of the best offers considered by United Airlines. Indianapolis won the competition, but that victory didn’t last long. The plant’s workforce peaked at 3,000, and the operation closed in 2003.

More: Oklahoma City businesses, nonprofits eligible for new round of COVID-19 relief funding

More recently, Foxconn, a Taiwan electronics manufacturer best known for its iPhone production, agreed to a deal in 2017 to build a $10 billion, 20-million-square-foot LCD display factory in Wisconsin that would employ 13,000. The deal called for incentives topping $4 billion.

Last year, however, Foxconn slashed the deal to one that would cap construction at $672 million and create just 1,454 jobs.

Greg LeRoy, executive director of Good Jobs First, sees the Foxconn and United Airlines deals as cautionary tales — deals with fatal flaws that were visible from the start.

“Foxconn is a poster child for a deal that never had the business basics,” LeRoy said. “The idea was to produce a product in the U.S. that was never produced in the Western Hemisphere. All the production and supply chains are eastern Asia.”

LeRoy saw a deal influenced with politics with then President Donald Trump and Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker proclaiming it as the start of bringing jobs back to the U.S.

“The tragedy is that the state doesn’t stand to lose much,” LeRoy said. “All the state money was performance based. It was based on hiring and investment.”

Mount Pleasant, the Wisconsin village of 26,000 chosen for the plant, wasn’t so lucky. Mount Pleasant paid $160 million up front to clear homes, businesses and properties to make way for the plant.

“There are some off-sets from the state that may cushion that blow, but not much of it,” LeRoy said. “The local government threw in land, demolished homes with eminent domain, committed water infrastructure and land parceling, and now they’re on the hook for $900 million. All they’ve gotten was flattened houses and a microscopic number of jobs.”

While Oklahoma City and bidders from across the country competed for the United Airlines plant, anyone with a newspaper stock page could see the company and the travel industry was not in great financial shape.

For the first six months of 1991, United reported a loss of $104 million, or $4.57 per share. Discount carriers were slashing fares to stay alive, and business travel was down due to a recession. That summer Oklahoma City paid for billboards outside of the United Airlines headquarters inviting the airline to “Come Fly the Friendly Skies of Oklahoma City.”

'There is almost never a tie'

LeRoy has looked at deals across the country and compiled research papers on best practices since founding Good Jobs First in 1998. Cities evaluated in the past include Oklahoma City. LeRoy said he isn’t anti-incentives, but rather wants to educate communities on how best to use them, when they might really be needed, and when they may not be a real consideration.

“Corporations and site section consultants have 100% control of the information about the company’s decision on where they are going to locate,” LeRoy said. “There is a history here that goes back to 1930 with several movement parts that we are all saddled with. You and I will never know, government and commerce will never know what Panasonic is thinking about and how they will make their decision.”

LeRoy urges communities to look at the greater picture, one in which companies look at costs and benefits, access to raw materials, labor and quality of life. Tiny differences in those factors, he said, dwarf the impact of incentives and tax codes.

“There is almost never a tie,” LeRoy said. “You also have to look at the benefit side. If they’re going to transfer executives to a place, they will look at quality of life, parks, schools and other amenities. If you can’t attract good smart managers to a place and you can't attract good employees from local high schools and vo-techs, you can’t have a deal.”

The loss of the United Airlines plant to Indianapolis in 1991 changed Oklahoma City forever as then Mayor Ron Norick surveyed the competing city and concluded it won based not on incentives but the quality of life factor cited by LeRoy.

It was then that the first Metropolitan Area Projects, MAPS, was conceived in which the money the city was prepared to spend on buying jobs instead was invested back in the community. The limited tax paid for a new ballpark and arena, revival of the Oklahoma River, a recreational canal in Bricktown, a downtown library, improvements at the fairgrounds and an extensive makeover of the city’s performing arts hall.

Voters approved of successful MAPS initiatives that rebuilt schools, added miles of trails and bike paths, built senior wellness centers, a new convention center and a large park. The latest MAPS focuses on social challenges including homelessness, mental health, justice reform and animal welfare.

With those ongoing improvements, Oklahoma City got back in the game of competing for major employers and started winning. They include homegrown Paycom, which employs more than 5,300 people; Boeing, which employs 3,600; Amazon, which employs 5,000; and Dell Computers, which employs 1,600.

More: Top Oklahoma lawmakers are pushing for tax relief. How much could it cost?

The city had significant losses, however, on early deals as it developed a system for evaluating incentives.

Oklahoma City taxpayers were left on the hook when the city council in 1999 approved a $2 million loan to a company that built cooling towers. The company moved to Oklahoma City, at one point employed 300, but then the workforce dropped to 60 as defects appeared in the cooling towers.

The company was unable to repay the loan and ended up bankrupt.

The city thought it had a done deal in 2000 when Corning Inc., then the world's largest fiber optics manufacturer, agreed to a package of tax breaks to build a $400 million plant that would employ 800 people.

The company already had spent $40 million on a steel structure for the plant when work was halted and the project was scrapped as the company reported a loss of $370 million. The company's debt status was cut to junk status.

Oklahoma City now has a three-step process for how it processes incentives deals starting with the Greater Oklahoma City Chamber. Jeff Seymour, vice president of economic development, is tasked with building industry awareness of the city with companies and site selection consultants.

“Incentives form a small part of it,” Seymour said. “They also look at talent, partnerships, infrastructure and flight access. One of the tabs we will look at is if there is assistance on the state level to help close this deal.”

Seymour said the chamber looks at about a half dozen deals each month, with about half of the them coming directly to the chamber and the other half provided by the Oklahoma Commerce Department.

Brent Bryant, who oversaw economic development programs in Oklahoma City for 12 years, and his successor, Joanna McSpadden, say each deal has its own challenges and opportunities, but the city has the same safeguards in place to protect city resources.

Those resources include millions approved twice by voters to be used for incentives deals.

“All of our agreements are structured as pay for performance,” McSpadden said. “We require those jobs to be paid at the agreed pay rate. They are required to maintain the hiring levels after the payout. And if we do any sort of loan or take out any debt, we perform reviews of finances to get guarantees to do the best we can to protect the city.”

Bryant said evaluators must take an honest look at what they have to offer a company.

“If you don’t have the labor force, you can’t give anyone enough incentives,” Bryant said. "Is it a good fit logistically? What’s the cost of electricity? What is the cost of water? They look at all that. And we’ve always ranked good on all of that. And we have a good cost of living in Oklahoma compared to East and West coasts.”

Before a deal gets to the city council, it is first reviewed by the Oklahoma City Economic Development Trust, whose members are appointed by the mayor and council. And even after all the scrutiny given by the chamber, the alliance and city staff, some deals still don’t make the cut.

“One in particular was a company that was a back-office call center,” Bryant said. “They were allowing people to work from home. Their target labor group were spouses of members of the military. That was one we looked at trying to be aggressive in helping get them, but we realized we could end up paying for someone who didn’t live in Oklahoma City.”

That deal ultimately failed as it was submitted to the development trust.

“We try to do a lot of due diligence,” Seymour said. “We want to see the management team. What is their history? What are their finances? How do they fit in with the broader industry they are in? We want to see if something is real before we plow ahead into something first.”

Seymour said the Panasonic deal represents an important opportunity for Oklahoma to get in on the ground floor of an industry that has a bright future.

“It feels pretty similar in a lot of ways to what was going on with the auto industry 20 to 30 years ago with the European car companies opening plants in the southeast and southwest. We’re seeing a lot of new start-ups and the creation of a supply chain all at once. There is a window of time where all of this is at stake. You have to think about when to lean into the wind and when not to.”

Steve Lackmeyer started at The Oklahoman in 1990. He is an award-winning reporter, columnist and author who covers downtown Oklahoma City, urban development and economics for The Oklahoman. Contact him at slackmeyer@oklahoman.com. Please support his work and that of other Oklahoman journalists by purchasing a subscription today at subscribe.oklahoman.com.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: State leaders wooing Panasonic factory can look to OKC on deal making