‘Incredible mind, incredible heart’: After decades fighting Ebola, a beloved expert hangs up his boots

On the last day of January, while most everyone who works on or worries about Ebola had their eyes trained on the latest dangerous outbreak, one of the world’s leading experts on the virus quietly retired.

Dr. Pierre Rollin, who has more Ebola field experience than almost anyone on the planet, shared a cake with close colleagues and cleared out his office at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He sent co-workers an email citing the lyrics to “My Way,” explaining he wanted the song to play when the email was opened but could not “find someone young enough to know how to do it.”

And then, after 26 storied years with the agency, Rollin took his leave.

Rollin had been deputy branch chief of viral special pathogens, the team at the CDC that handles the deadliest known viruses, as well as the head of epidemiology for that group. A physician by training, he worked in the highest-security laboratories, studying what Ebola viruses do when they infect. But he also did much, much more.

He is renowned among the hardcore community of people who work on Ebola (and on Marburg fever, a related virus) as a jack-of-all-trades, someone who is able and willing to do nearly anything that needs to be done during an outbreak.

Stay up late into the night entering data? Not a problem. Dig a grave? Someone has to. Explain infection control to the staff at a local hospital? Great idea. Trap animals to try to see where Ebola hides in nature? Why not?

His former boss at the CDC, Dr. Inger Damon, recounted having seen a photo of Rollin’s legs sticking out from under a truck he was repairing; the picture was taken during a 1993 hantavirus outbreak in the United States.

“He is unusual in that way. He has incredibly diverse knowledge. And then he’s just willing to do it,” said Dr. Dan Bausch, who worked for Rollin at the CDC from 1996 to 2003. “Another person would say, ‘I’m not here, damn it, to go out and dig a grave.’ … And Pierre was always willing to do whatever needed to be done.”

Many of the people Rollin worked with over the years, in outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or Angola, Mali or Uganda, are having a hard time picturing the field without him.

“He’s just a giant,” said Dr. Mike Ryan, a veteran of outbreak responses who is assistant director of the emergency preparedness and response program at the World Health Organization. “Pierre has been a constant presence in the world of emerging diseases for well over three decades. … His dedication to this task has been super human. He’s an incredible brain, incredible mind, incredible heart.”

“It’s hard to speak of him without going into hyperbole, you know?”

Rollin declined a request for an interview with STAT. But friends from the field said he had discussed the possibility of moving on for several years. Outbreak responses these days had become more centralized than they were in the past, with the people assigned to response teams bringing more specialized expertise. And Rollin didn’t enjoy the new normal.

In videotaped interviews about his career recorded for the Global Health Chronicles — a CDC and Emory University collaboration to memorialize public health responses — Rollin said he was “grumpy” about the way things had changed.

“We used to be able to do everything. That’s how I was trained. There is no way I can train anybody else to do the same thing now, because the same thing doesn’t exist,” he said. “It’s a new normal but I liked the old normal much better.”

When STAT asked to interview him on his retirement, Rollin said he didn’t want to talk about himself. “I think I was only a ‘brick in the wall’ and nobody deserves to be a star,” he said in a brief email.

But others in his field — people who have worked with and learned from Rollin in outbreak after outbreak, who quarreled and laughed with him, tested blood samples and dug graves with him — were not willing to let his retirement pass without paying tribute to his contribution.

“We are all replaceable,” said Dr. Heinz Feldmann, who led the research into the development of the experimental Ebola vaccine being used in the current outbreak in DRC and who directs the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’ virology laboratory in Hamilton, Mont.

But, he added, it “will take a long time to find someone like him who knows every area pretty well and has been out in the field so many times.”

Rollin, who is 66, was born to French parents in Morocco when the North African country was still a colony. When he was a teenager, the family — he is one of eight children — moved back to France. He initially planned to study to be a veterinarian, but switched to human medicine. One of his professors got him interested in epidemiology, sparking a curiosity about zoonoses — the diseases, like Ebola or West Nile, that pass from animals to people.

He was later hired at the Paris-based Pasteur Institute, where he had encounters with many of the greats of virology, including Karl Johnson, who led the response to the first Ebola outbreak and who named the virus.

In 1989, Rollin went to the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases — USAMRIID — at Fort Detrick, in Maryland, to do postdoctoral work. He arrived at a career-shaping time.

Research monkeys imported from the Philippines were dying horrifically in a quarantine station at Reston, Va. Testing revealed they were infected with a new type of Ebola — now known as Reston ebolavirus. At the time, no one knew if this type of Ebola could transmit to people; the only two other types known then, Zaire and Sudan, were fearsome killers. (It turned out Reston ebolaviruses can infect but do not sicken people.)

Rollin (center) loads special equipment onto a truck in northern Uganda in October 2000. (Sayyid Azim/AP)

Dr. C.J. Peters, the legendary virologist, was head of USAMRIID’s disease assessment division and was running the response. Rollin was pressed into service.

“And he must have liked it because after I took the job at CDC” — Peters was named head of viral special pathogens at CDC a couple of years later — “and Pierre approached me for a job. And I was only too glad to have him,” Peters said.

Peters said that working with Rollin was not always a joyride. He could be a “handful” to manage.

“I think he’s great — although there have been times when I would like to have wrung his neck.” (That may be a characteristic common to people drawn to this type of work. When STAT wrote about Peters last year, Johnson described Peters in much the same way.)

Peters, who is now retired, said Rollin would look at a situation in which “people may think that it’s X and Pierre’s going to think it’s Y. And that is actually one of his strong points, I think.”

The downside: “If you had a little plan that you had drawn up to do something and there was a hole in the plan, Pierre would find it and tell you about it,” Peters recalled.

Surely that, though, was for the best? “Yes, it’s the best thing. But it doesn’t feel good while you’re having it done,” he noted.

Rollin shared something else with Peters: a preference to be where the action was, not home and close to bosses.

“I was very happy when I was in the field. I was very disappointed when I was here,” he told the Global Health Chronicles project, describing the West African Ebola outbreak. In a stint in Atlanta during the two-year outbreak, Rollin spent a month-and-a-half working in the CDC’s emergency operations center — the hub from which emergency responses are run. “It’s hell,” he said.

“Pierre Rollin is really boots on the ground,” said Gary Kobinger, who has shared many field experiences with Rollin.

Read more: The virus hunter: In a bygone era, C.J. Peters learned how to bend the rules

Bausch, who also worked with him on many Ebola and Marburg outbreaks over several decades, said the only thing Rollin had trouble handling was bureaucracy.

“Where he would really blossom is when you got into the field with him — because he got away from the mothership. He could have a little bit of room to do things,” said Bausch, director of the U.K. Public Health Rapid Support Team, a partnership between Public Health England and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Though Rollin was often the most experienced person on a response team, he didn’t pull rank.

“He would be the first guy to take the worst bed or the worst room,” said Bausch, who often ended up sharing a room with Rollin in whatever accommodations could be scrounged up during outbreaks, which often occur in remote and low-resource settings. “He really was not arrogant at all in that way, and very sacrificing for the team.”

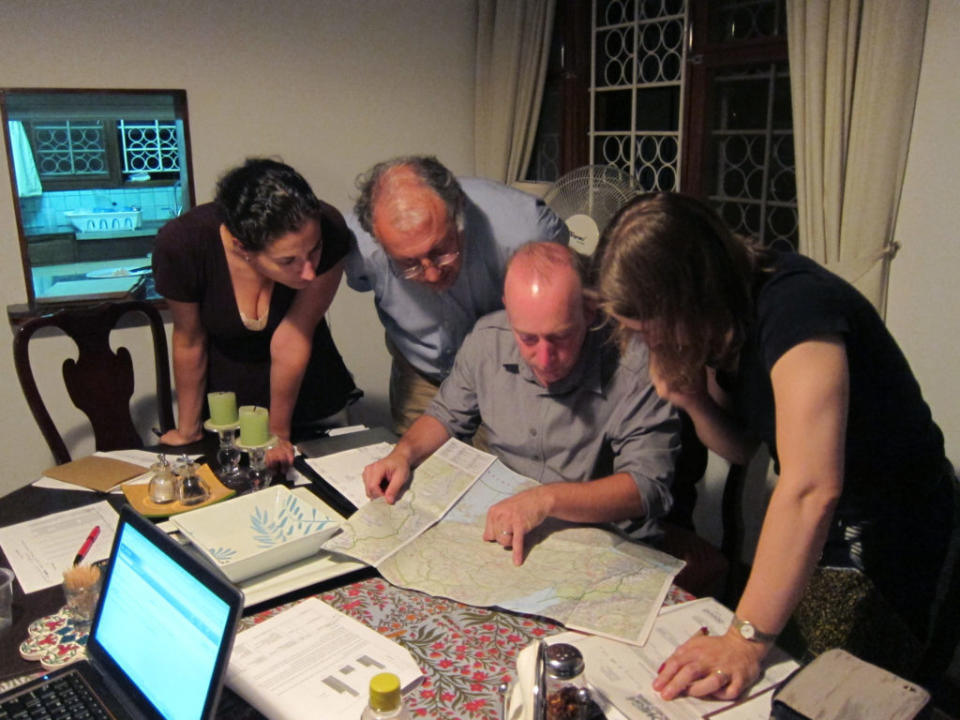

Epidemiologists and others, including Rollin (second from left), gather in Uganda during the nation’s Ebola outbreak in 2012. (CDC)

In outbreak after outbreak, colleagues said, Rollin was an invaluable resource for others.

Kobinger, who led the work to develop the experimental Ebola treatment ZMapp, said people would seek out Rollin when something was going wrong, “and he’d come up with a story that was 10 times worse.” The upshot is the person would walk away feeling things weren’t so bad after all, said Kobinger, who is director of the Infectious Disease Research Center at Laval University in Quebec.

Rollin was known for putting in long hours in the field, but also having the handy skill of being able to nap anywhere, anytime. A snooze in a meeting was not unknown.

Under Peters, Rollin became the head of the pathogenesis section at the CDC. His friends said he is very good diagnostician and is adept in a BSL-4 lab, the high-containment laboratories where scientists work on the deadliest pathogens. “Very good with his hands in doing that work,” said Bausch, who learned BSL-4 technique from Rollin.

If Rollin was good with viruses, he was equally as good with people. Damon, his former CDC boss, recalled that when one of the nurses from Dallas who had been infected with Ebola in 2014 gave birth well after she had recovered from the virus, there were still niggling concerns about whether she could infect others. So Rollin flew out to be on site, just in case.

“That’s just the kind of guy he is,” Damon said.

Read more: Ebola vaccine will be provided to women who are pregnant, marking reversal in policy

There are fewer and fewer all-rounders like Rollin in the outbreak response community and some see his retirement — which he has been threatening for several years — as almost an end of an era. Kobinger noted that last spring, during an outbreak on western DRC, everyone wanted to take a selfie with Rollin, figuring it might be his last.

Rollin was briefly in the field during the current outbreak in northeastern DRC, back in August when the response was just starting up. A violent incident in the area — one of many that has plagued this outbreak response — prompted the State Department to order U.S. government employees to leave. They haven’t been allowed back since, though Rollin did spend time in the Congolese capital, Kinshasa, advising the health ministry.

In retirement, Rollin plans to split his time between a family farm in France and Atlanta, where his wife, Dominique, still works for the CDC. But many of his friends and colleagues are hoping his leave isn’t permanent, and wonder if he’ll end up working for Doctors Without Borders or some other entity that would take him back to the field.

“Somehow I can’t see Pierre retiring to the Camargue for long periods of time,” Peters remarked.