Incumbent Presidents Have Faced Vicious Primary Challenges. Why Isn't Joe Biden?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

President Joe Biden is running for reelection. But a lot of Democrats would rather vote for someone else.

Sixty-seven percent of Democrats say they want a different candidate, according to a CNN poll released in September. That’s down from 75% who said the same in the summer of 2022, but it’s still extremely high for a sitting president.

This has a lot of pundits all voicing the same question. A recent New York magazine piece by Jonathan Chait asks: “Why isn’t a mainstream Democrat challenging the president?” In The Washington Post on Wednesday, David Ignatius argued that Biden should step aside. Back in February, liberal New York Times opinion columnist Michelle Goldberg also argued that Biden shouldn’t run again. That same month, journalist Mark Leibovich put forward his “Case for a Primary Challenge to Joe Biden” in The Atlantic.

So far, no serious candidate has emerged to challenge Biden. The reason may be fairly simple. Incumbent presidents are rarely replaced, whether via the old smoke-filled rooms of party bosses or in the plebiscitary field of the modern primary election system. And when they do face serious, existential challenges, their challengers tend to highlight the incumbent’s weaknesses, bruising them for the general election.

Since political parties tend to want to win elections, just as the individual politicians do, it takes particular circumstances for someone to mount a challenge. It usually requires an ideological divide within the incumbent’s party that a challenger can capitalize on. But Biden’s Democratic Party doesn’t appear to have the kind of rancorous divides that existed when previous incumbents faced real challenges.

This kind of internal strife, by contrast, was highly visible during the last three serious primary challenges to incumbent presidents, in 1968, 1976 and 1980.

President Joe Biden is not facing a primary challenge from Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (center) or any other serious Democratic politician.

In 1968, the Democratic Party was viciously divided over multiple issues ― from civil rights and segregation to crime and rioting in the cities ― but the biggest issue that cleaved the party was the Vietnam War. Sen. Eugene McCarthy (Minn.) launched a primary bid in 1967 against President Lyndon Johnson largely as an anti-war protest.

Following the disaster of the 1968 Tet Offensive, McCarthy surged into second place in the New Hampshire primary with 42% and held Johnson under 50%. Four days later, Johnson’s most feared opponent, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (N.Y.), entered the race. Johnson announced he would not seek reelection a few weeks later. Following Kennedy’s assassination, the party bosses selected Vice President Hubert Humphrey as their candidate, but the divisions over Vietnam crippled his candidacy, leading to a loss to former Vice President Richard Nixon.

Eight years later, President Gerald Ford faced a primary challenge from former California Gov. Ronald Reagan. While occupying the White House, Ford was an unusual incumbent, having never run for the office of president or vice president but instead rising to the Oval Office following the double scandals that led to the resignations of Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew. His lack of a national electoral record provided a strong rationale for a primary challenge.

A longtime GOP star, Reagan was aligned with the rising New Right ― a collection of free-market economists, anti-civil rights populists, neoconservatives and right-wing evangelicals. Ford represented the clubby moderation of the old Republican elite, committing the heresy of choosing Nelson Rockefeller, the icon of liberal Republicanism, as his vice president. Reagan represented a new breed of assertive conservatism that dreamed of fusing a new governing majority and overthrowing the New Deal order that, as they saw it, Republicans like Ford had come to accept.

Reagan’s bid took off when he latched on to an issue of patriotic emotional resonance: the agreement to hand over the Panama Canal to the Panamanian government. By the time of the party’s 1976 convention, Reagan trailed Ford by fewer than 50 delegates. The GOP coalesced around Ford, but Reagan stole the show with his rousing convention speech, setting the stage for his comeback in 1980. Ford ultimately lost his first real election campaign to Democrat Jimmy Carter.

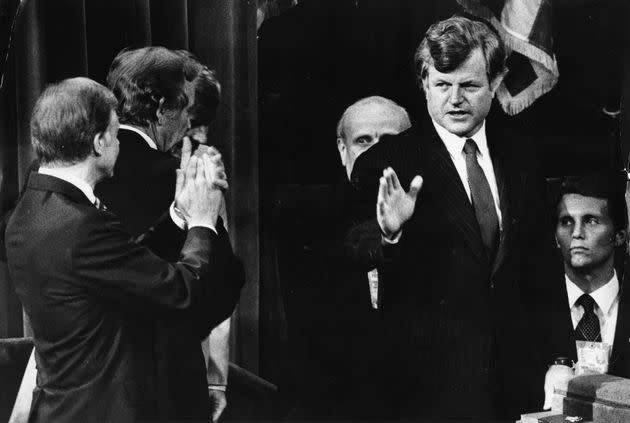

When Carter, now the incumbent, ran for reelection in 1980, he faced his own primary challenge from another Kennedy ― specifically, Sen. Ted Kennedy (Mass.). Carter, a Washington outsider and the first candidate to capitalize on the new primary rules instituted in 1972 that removed power from party insiders, bucked the Democratic establishment by breaking with labor unions while pushing deregulation of business and technocratic management of government. The president also frequently clashed with congressional Democrats, creating a rift in the party.

A rancorous primary led to an awkward photo op between challenger Sen. Ted Kennedy (Mass.) and President Jimmy Carter at the 1980 Democratic National Convention.

Kennedy stepped in as the standard-bearer of the old Democratic faith, and a tribune of the New Deal coalition crumbling beneath the party’s feet. But even before he announced his primary bid, he stumbled when he couldn’t answer the seemingly easy question of why he wanted to be president. Carter bested Kennedy in the primary campaign, but Kennedy refused to drop out before the convention, leading to bitter divisions within the party. Carter went on to lose badly to Reagan.

If we want to go back further, Teddy Roosevelt’s challenge to President William Howard Taft in 1912 represented a divide within the GOP between progressives and conservatives. Other lesser primary bids, like Pat Buchanan’s 1992 bid against President George H.W. Bush, featured similar ideological divides, with Buchanan’s proto-Trump right-wing nationalism rallying against Bush’s moderate internationalism. Even further back, the last time an elected incumbent president made a serious bid for renomination and was denied was in 1856, when Democrats replaced President Franklin Pierce with former Secretary of State James Buchanan. And that was during the old days of cigar-chomping party bosses. This is how rare it is to succeed in challenging an incumbent.

For the sake of making a comparison to Biden’s predicament, let’s focus on the three most recent examples of incumbents facing significant primary challenges.

They have a number of things in common. First, the challenges all represented real factional divides within their party. Second — and this may sound like it should be a given — they all ran with the intent of actually winning the nomination. (Maybe not McCarthy, but definitely RFK.) And, third, in each case the incumbent party lost the ensuing general election.

In Biden’s case, none of the primary candidates floated by pundits to challenge him represent any kind of factional divide within the party.

Do big names like Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, California Gov. Gavin Newsom, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore, Sen. Raphael Warnock (Ga.) or Sen. Chris Murphy (Conn.) have any real policy objections to Biden’s governance? Do they represent any faction within the party that is particularly, or even somewhat, aggrieved by Biden’s actions? No.

Were a challenge to emerge based on an internal divide, you would expect it to come from the party’s left wing. But Biden has deftly cultivated relationships with the party’s left. He includes Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) in policy-making decisions, and considered appointing him as labor secretary. Biden’s administration is filled with former staffers of Sen. Elizabeth Warren (Mass.). And he listens to labor unions. The younger standard-bearers of the Democratic left are either too young to run, like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (N.Y.), or are content to wait, like Rep. Ro Khanna (Calif.).

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (N.Y.), a leader of the Democratic Party's left-most faction at age 33, is currently too young to run for president.

The lack of genuine internal party divides would sap any prospective primary bid of the most common force that prompted them in previous elections. But as Democratic voters and pundits note, a challenge to Biden would emerge not over policy differences, but over aesthetics and fears of continuity.

You see, Biden is old. At age 80 now, he is the oldest person ever to serve as president. If reelected, he would finish his second term at 86. In that recent CNN poll, 64% of Democrats listed age, mental acuity or health as their biggest concern about Biden. Whether or not Biden is intensely and actively involved in directing his administration ― and in his recent book, “The Last Politician,” Franklin Foer makes it clear that he is ― he looks old, and Democrats worry that is hurting his reelection chances.

“Biden’s age isn’t just a Fox News trope; it’s been the subject of dinner-table conversations across America this summer,” Ignatius wrote in his Washington Post op-ed calling for Biden to step aside.

The idea, seemingly proposed by pundits, is that a primary challenger will emerge and will, very nicely, without attacking Biden’s age, usher him off the stage, à la Johnson in 1968. This would somehow also push aside Vice President Kamala Harris. But if the question of Biden’s age is the paramount issue, it would be impossible for a challenger to avoid commenting on it — especially if, like Reagan, the Kennedys and to a lesser extent McCarthy, they are running with the intent to win.

This is obviously extremely fraught. What politician who hopes to have a future in their party wants to attack their incumbent president as too old, and then ― based on the history of challenges to incumbents ― probably lose a primary campaign? Attacking Biden as senile didn’t exactly work out for former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro in 2020. He was booed by the debate crowd and denied a speaking spot at the party’s 2020 convention.

The only elected Democrat who has even half-floated a 2024 primary bid, Rep. Dean Phillips of Minnesota, has repeatedly denied that Biden’s age is an issue, dodged questions about it and failed to explain exactly how he would win.

Party insiders aren’t just looking out for their own careers when they refuse to attack Biden’s age. They’re also looking back at the general election losses that followed each significant primary challenge in 1968, 1976 and 1980, and even the lesser challenge to Bush in 1992. Whether or not political scientists agree that primary challenges to incumbents damage them in the general, the politicians directly engaged in politics sure think they do.