Independence Day 100 years ago in Louisville: Peace, prosperity and prejudice

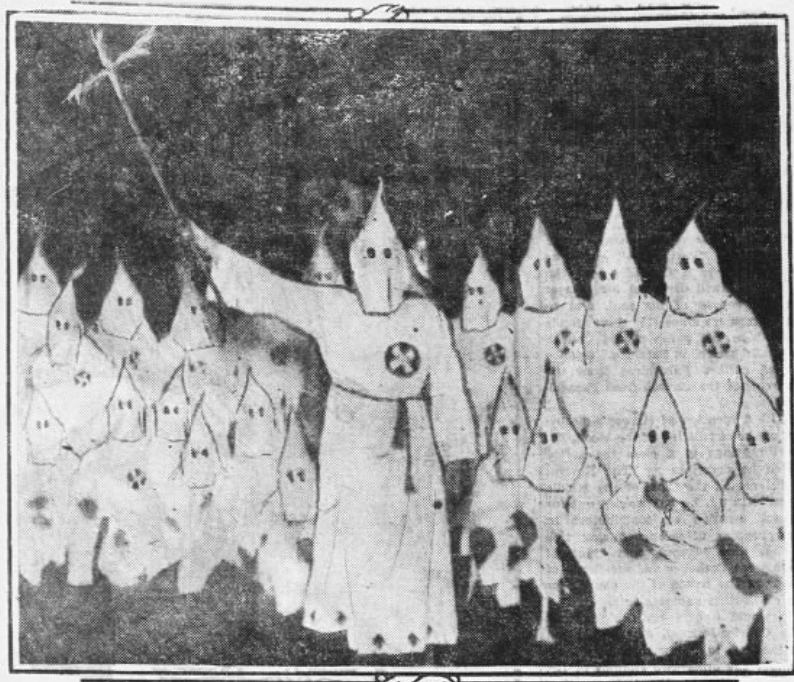

As the July Fourth weekend kicked off 100 years ago in Louisville, under the cover of darkness 53 robed members of the Jefferson Realm of the Ku Klux Klan burned a fiery cross before boarding a train to Kokomo, Indiana, for what turned out to be the biggest KKK rally ever.

A Courier Journal reporter mocked them as “Klownsmen” and wrote that if “they expected to create a furor, they were disappointed.” Three police officers who stood across the street yawned and then directed their attention to more important matters, the reporter observed.

Most Kentuckians had different entertainment in mind on July 4, 1923, as they celebrated the nation’s 147th birthday.

Thousands flocked to Bardstown to celebrate the transfer of the Federal Hill estate to the state of Kentucky, which rechristened it “My Old Kentucky Home" after the famed song written by Stephen Foster. In so doing, they made it Kentucky’s first state park.

Others stayed in town for fireworks and a 48-gun salute at Tyler Park, or to watch the Boy Scouts stage a “sham battle” at Harrods Creek or ride in a “10-mile automobile parade through the beauty spots of Louisville.”

There was plenty to celebrate.

Five years after the end of World War I, peace and prosperity ruled the land. The scourge of the influenza pandemic that claimed 20 million lives worldwide and 11,852 in Kentucky was over. Women in the state could finally vote, after the Kentucky General Assembly ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

And according to James Bond, who was director of the Interracial Commission of Kentucky, “Negroes and white people had reached a mutual understanding which tends to foster good will and interracial cooperation."

But Bond, who was born to an enslaved mother and her white master 60 years earlier while the Civil War raged, may have been overly optimistic. The most recent lynching of a Black man in Kentucky had occurred just two years earlier in Woodford County, and most institutions in the state, including public schools, were strictly segregated.

Progress for Black Americans in Kentucky was moving at a glacial pace.

The city of Louisville had just approved a “negro fire company,” but wouldn’t allow Blacks to serve with white firefighters. And for the first time in Kentucky, an all-Black jury was selected in Perry County to try “a member of their own race” for murder. They deliberated only three minutes before finding Ed O’Neal guilty of manslaughter and recommending he serve 21 years in prison.

Life itself was unequal for the Black population.

While a white baby born in Kentucky in 1923 could expect to live for 57 years, the life expectancy for Black newborns was only 48 years. Black Americans were nearly twice as likely to die of tuberculosis than whites and more than twice as likely to succumb to pneumonia. They were 13 times more likely to be a victim of homicide.

Then, as now, civic leaders bemoaned Louisville's soaring number of murders and that most went unsolved. The city, with 235,000 people, was the nation’s 34th largest but had the sixth-highest murder rate. Only “drastic federal regulations for the control of firearms” could solve the problem, pronounced the Spectator, an insurance industry journal.

"The record since 1900," it said, "reflects an attitude of lawlessness and indifference to human life without parallel in the history of mankind.”

Women, or at least white women, seemed to be making more progress than Black Americans.

Mary Elliott Flanery of Carter County had been elected to the state House of Representatives a year earlier, the first woman in any state legislature south of the Mason-Dixon line.

A story in the Louisville paper declared that “Twentieth Century women, experts with firearms and in the realm of sports, are ready for the front line trenches, if they are ever needed.”

But male and female business leaders at a symposium convened by the League of Women Voters sharply divided on whether they were ready for executive roles.

"One executive with whom we talked said he had found that able women are much more likely than able men to shun responsibility,” a league spokeswoman said at the time. “He offered two explanations, the first that women are often carrying two jobs, one at home and another in the office; the other, is that they have a certain dependent attitude of mind,” though he said that "mothers ought to be able to control that in the next generation.”

Meanwhile, The Courier Journal’s advice columnist, Dorothy Dix, urged “young maidens to walk warily” because the summer months were “open season for male flirts” whose minds turn to “vacations and philandering.” One of the most difficult things in the world for a woman to tell, she said, is "when a man’s attentions mean intentions” — that is, whether they will “amount to a wedding ring or are just plain hot air.”

Also a panel of judges selected Dorothy Heick, of 1631 Eastern Parkway, who stood 5 feet, 5 inches tall and weighed 130 pounds, as the “most typical girl in Louisville,” earning her the right to compete with girls from every county for statewide honors at the University of Kentucky later in the year. The winner would be appointed the honorary sponsor of UK’s new football stadium.

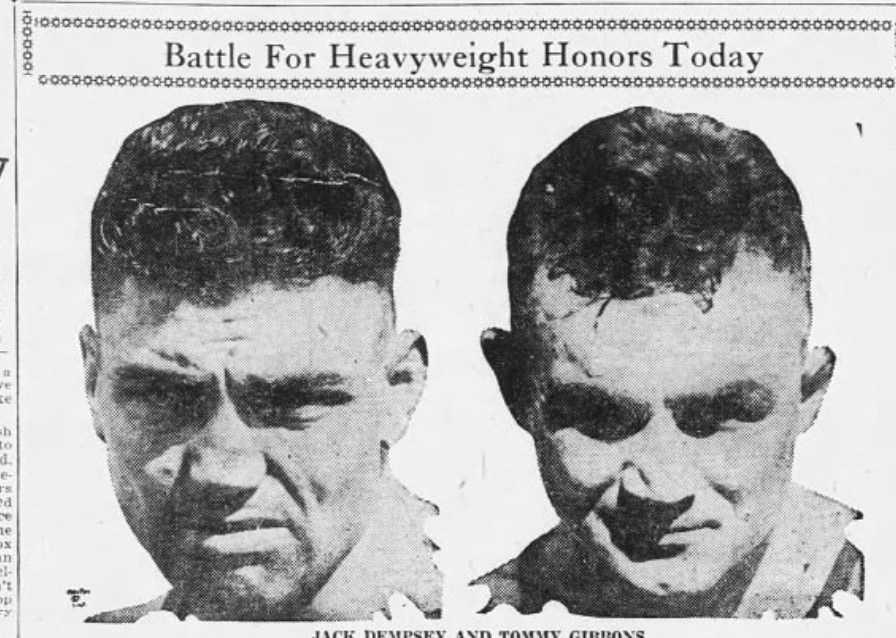

In the sporting world, all eyes were on tiny Shelby, Montana, a two-block cow town where on July Fourth heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, the Manassa Mauler, would defend this title against Tommy Gibbons. WHAS promised to broadcast the fight over what it called a “radiophone.”

Promoters hoped the bout would put Shelby — about 30 miles south of the Canadian border — on the map and ignite a real boom. But at the opening bell, about 4,000 ranchers and farmers stormed the gate and only 7,202 people paid to attend to see Dempsey win by decision in 15 rounds. They were described as “a mix of oil millionaires, Blackfoot Indians, cowboys, shepherds, hookers and sportswriters.”

The biggest loser was the town itself. Four of its banks went under in what was called the “biggest financial disaster in pugilistic history.”

As Louisvillians celebrated the Fourth, The Courier Journal’s “arctic radio correspondent,” Donald B. Macmillan, steamed toward a polar village on an 89-foot schooner crammed with “modern wonders” like motion pictures and a wireless radio. Such items, he said, had “never dreamed of by the northern aborigines, who in length of civilization are separated from the white man by thousands of years.”

“What will the Eskimo flappers do when the radio picks up the latest jazz?” he asked.

Four weeks after Independence Day in 1923, the Ku Klux Klan opened an office in the Republic Building at Fifth and what was then called Walnut Street to launch a membership drive.

A man identifying himself only as Ti-Bo-Tim told a Courier Journal reporter that membership cost $10 (the equivalent of $181 today) and was available only to American-born white men over 18, with “church members preferred.”

But unlike across the river in Indiana, where Klan membership in the 1920s became the largest in any state, the KKK never took off in Louisville.

The reason was simple, historians later said. Louisville Mayor George Weissinger Smith was a Republican who owed his election to Black, immigrant and Catholic voters. And to return the favor, his administration refused to grant the Klan a permit to meet or march in Louisville. While the Klan would loudly protest this decision, it was never overturned, and throughout the 1920s Klansmen and Klan meetings simply were not seen in Louisville.

More: 'Censorship by PIO': Kentucky agencies' strict media rules putting a gag on workers

Reporter Andrew Wolfson can be reached at (502) 396-5853 or awolfson@courier-journal.com.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Fourth of July: Here's how the holiday looked in Louisville in 1923