The Partition provoked the greatest forced migration in history — and it's not widely known

“I had friends who were Muslims, you know.”

It was late 2019, and I was trying to untangle the threads of my father’s rapidly fading memory. When I asked him to tell me his story, I didn’t expect him to start there.

My father was born into an upper caste Hindu family in colonial Kolkata (then Calcutta) in 1934. His father, my Thakudar, was a physician. Thakudar grew up in an isolated village where medical care was out of reach. Haunted by the memory of his mother’s early death, he moved his family to a rural community in the western part of the state of Bengal when my father was a small child.

My dad grew up swinging like Tarzan on vines near a pond and playing soccer with the giant jackfruits that fell from the trees. At night, he could hear the grumbling roars of Bengal tigers in the surrounding jungle. These stories, part of the fabric of my childhood, always sounded exotic and thrilling.

And then, everything changed.

At midnight on August 15, 1947, the Indian subcontinent was released from British rule. As the country was divided into two separate republics, one Hindu-majoirty and the other Muslim-majority, freedom celebrations were rapidly overshadowed by horrific violence. In the chaos that ensued, “Fourteen to 15 million people were displaced. One to two million people died. Families were separated,” filmmaker Neha Aziz said during an intimate roundtable discussion among Austin Desi creatives in the Statesman studio in late 2022 shortly after the final episode of her excellent podcast “Partition” aired.

Over 10 episodes, Aziz’s podcast explores the lasting impacts of Partition through interviews with survivors and scholars, historians and artists. She takes an unflinching look at the nightmarish violence, dedicating two episodes to the specific horrors faced by women who were raped and brutalized, dismembered, kidnapped and sometimes murdered by their own families to preserve their “honor.” She studies the way the aftereffects of Partition echo through the lives of every family that lived through it, even generations later and even among families who shrouded their experience in silence.

“It really shapes, I think, every South Asian today,” said Aziz.

More: Pride of India showcases Indian culture at annual Austin celebration

Partition provoked the greatest forced migration in human history

As India inched closer to independence, Thakudar followed the news closely. Hindu and Muslim political leaders clashed over how to govern the new republic, while the British government, financially depleted from World War II, searched for a hasty retreat. As a plan emerged to cleave the country in two, to divide it along nebulous lines, Thakudar sensed impending trouble in the Muslim-majority region that would become East Pakistan (and later Bangladesh). He sent his wife (my Thakumar) and three teenage daughters back to Kolkata. My father and Thakudar were the only family members still in the house when a group of Muslim men, friends from the village, arrived at the door with an ominous warning: It was time to flee.

The Partition of India and Pakistan provoked the greatest forced migration in human history. The British, eager to abandon the prized imperial conquest of yesteryear rather than become embroiled in brewing sectarian conflicts, hacked nearly a year from the original timeline for dividing the former colony. Communication was dismal and in the absence of a clear plan, the country descended into tribalism. Mobs took to the streets. Neighbors turned on each other in grisly acts of barbarism. By the time the actual boundary lines for the two new republics were announced on August 17, the formerly unified state of Punjab, now split between Northern India and Southern Pakistan, was drenched in blood.

Neha Aziz’s grandfather, her dada jaan, was among the Muslims who fled the newly anointed India. He was a young teenager at the time. His story of a harrowing journey — traveling alone by boat for 14 hours to reach an uncle in Karachi — forms the backbone of the opening episode of “Partition.”

Her family and mine crossed borders in opposite directions to escape mirrored atrocities.

In the podcast, Aziz’s dada jaan speaks of his family’s relocation as a choice, but Aziz disagrees with this assessment. Her family gambled on a better life in a land where they would not be minorities. The alternative was fraught with danger and devastation, almost certain loss of property and possibly loss of life.

But “India was their home,” she said. To leave it behind was heartbreaking.

The biggest historic event that you never learned about in school

Though Partition left an indelible mark on millions of people from the most populous country in the world, it is rarely taught, examined or interrogated outside of the subcontinent. In the West, it’s barely a blip in a paragraph about the end of WWII in an AP World Cultures book.

Aziz, a native of Pakistan who grew up in Texas, had no concept of the terrible truth until she stumbled across an exhibit in a mall in Karachi when she was 27 years old.

“I think that people are very incredulous when they listen to the podcast. (They) think that it's impossible for someone who's an immigrant or a refugee or what have you to not know about this history,” she said.

The Austin Desis at our roundtable described similar experiences.

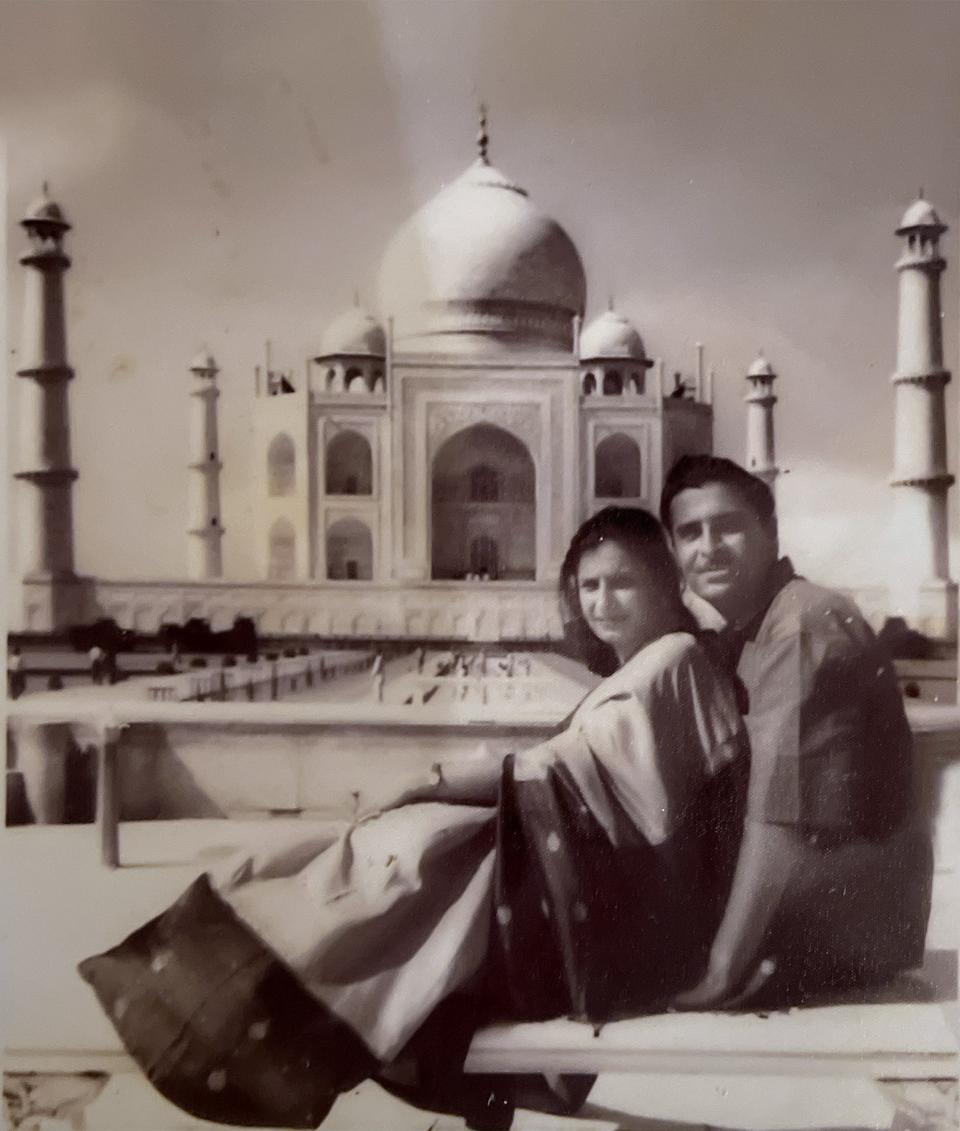

Many survivors buried the trauma of their experiences. I grew up with a vague understanding that my father was a refugee. We have a photo of my Thakumar on her wedding day, adorned with gold. My father used to lament how most of it was lost during his family’s flight. As an adult, I understand how privileged we were. That gold bought his family safe housing and passage. We didn’t have to face the horror empty-handed.

“How I found out about partition, actually, was reading (‘Midnight’s Children’) in a magical realism class in grad school,” Nadia Chaudhury, editor of Eater Austin, said during the roundtable. Chaudhury’s parents were born in East Pakistan after Partition.

My own understanding of Partition was also shaped by Salman Rushdie’s 1981 novel as well as Vikram Seth’s soaring post-Partition epic, “A Suitable Boy.”

Ramesh Srivistava’s father was born into the tumultuous post-Partition world and grew up with the “trauma that comes as a result of kind of the long arm of colonialism,” the lead singer of the popular band Voxtrot said during the roundtable. Srivastava’s family were prosperous landowners during India’s colonial era. After independence they were “essentially extremely poor,” he said.

His father grew up in a mansion in Lucknow — but it was crumbling. His mother was very ill and at 11 years old, Srivastava’s father became a primary caregiver. “There was no money, so it was a really hard experience for him,” he said.

In the new world, the ties we maintained with my father’s family felt tenuous. He seemed eager to leave his past behind. I don’t know how much the horror of Partition played into his feelings, but watching the world he loved shatter surely made it easier to leave.

“Also just in general, the South Asian parents, they look to the now and forward, right? Their focus is making sure their children are OK,” Chaudhury said. “That they have enough money to support us and keep us safe.”

‘I worry a lot about my parents’

Coming of age in rural Ohio in the ‘80s and ‘90s, I was plagued by a sense of placelessness. I was born in America, but did I really belong here? Each month, my father sent money home to support his family in India, but for years, my Thakudar didn’t spend the money. Instead he put it in an account, fearing one day our family would be forced to leave.

When America became engaged in the Gulf War in 1990, I was horrified by the gleeful way my neighbors embraced the carnage. People wore gruesome T-shirts, images of hook-nosed Arabs impaled on American tanks. When I brought up the war’s excessive civilian casualties in a high school government class, I was accused of being part of a Muslim brotherhood.

There was a fervor around killing people who looked like me, and it shook me to the core.

A little over a decade later, that fervor resurfaced with amplified intensity in the wake of the attacks on America perpetrated by Saudi Arabian terrorists on September 11, 2001. America cast a suspicious and hostile eye on Muslims as well as anyone who looked like they might be Muslim.

Chaudhury was in high school in New York City at the time.

“We would get looks,” she said. She was once stopped by a police officer for taking photos near a subway. It was chilling. “I think about what my parents probably never told me about what they probably experienced,” she said.

Aziz nodded in agreement. “My dad worked at a convenience store. I don't even want to know,” she said.

The anxiety Srivastava, then 18, felt as “a single brown man going through security” at airports lingers to this day.

Aziz jokes about how she needs “to save extra time for racial profiling,” when she travels.

In recent years, as mainstream American politicians in Texas and around the country push a Christian nationalist viewpoint, concerns among religious minorities are on the rise.

“I worry a lot about my parents,” Chaudhury said. Her family still lives in New York. “There's been a lot of anti Asian American stuff happening, a lot of that harassment, and I don't like the idea of my dad on the subway.”

“This move toward what feels like a theocracy, to me, is one of the most terrifying things,” Srivistava said. “The fact that more people are not horrified by it is so crazy to me.”

‘We’re learning from each other’

While anti-Asian sentiment might be on the rise, South Asian visibility in mainstream media is at an all-time high. Aziz dedicated an episode of her podcast to depictions of Partition in TV and film.

She interviewed the writer Fatima Asghar, whose collection of poems, “If They Come For Us,” is centered on Partition. Asghar was also a writer on the Marvel television show “Ms. Marvel.” The series follows the journey of a young Muslim superhero Kamala Khan as she discovers the secrets to her powers are tied up in her family’s Partition story.

A key moment in the series depicts a chaotic and terrifying scene at a train station full of people desperately trying to flee. “I think for most people in the West, I don't know that they’d really seen images of Partition,” Asghar says on the podcast.

After that episode aired, Google searches for Partition skyrocketed. Asghar saw South Asians on Twitter talking about how they’d never collected their family’s Partition stories. The episode inspired them to ask questions.

Aziz also talked to Shanti Thakur, whose independent film “Terrible Children” is based on her father’s experience.

For children of parents who went through Partition, “a part of our healing is to understand what happened on a micro level and a macro level,” she says in the podcast.

“Let's have a conversation and let's start to make observations and share these observations with each other about how this affects us and how this affects our families,” Thakur says. “Moreover, how do we survive it and how does it make us stronger?”

In some American immigrant communities rifts remain between Hindus and Muslims, Pakistanis and Indians. But for many of us who grew up in the new world, our commonalities far outweigh our differences.

“We're all South Asian and that's really cool,” Chaudhury said near the end of the roundtable. “We're learning from each other. (We have) different experiences.”

There’s no “timeline on when you can learn new things,” Aziz said.

In a moment of extreme divisiveness in America, “my hope is that people, including us, use all of this information, all of this knowledge of history,” to help us see that “all human beings are truly equal,” Srivastava said.

Sharing these stories can help us move forward together.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Austin-based Partition podcast reconstructs history, looks for healing