Indiana Center for Recovery wants to build group homes near future Hopewell neighborhood

A drug and alcohol recovery business wants to build two group homes on First Street, but neighbors, including the city council president, said the project's scale and services do not fit into the neighborhood.

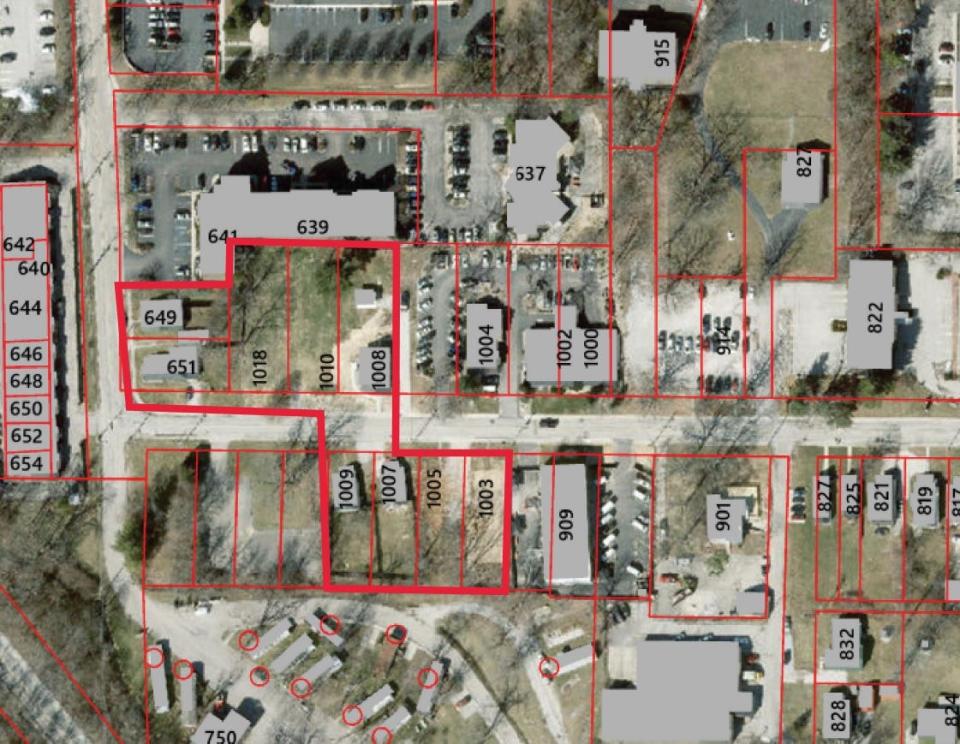

Indiana Center for Recovery wants to build one three-story group home and one two-story group home on opposite sides of West First Street, just east of the intersection with South Walker Street.

The building on the north side would have three stories, offices, meeting rooms and 31 apartments with one or two bedrooms. The south side building would have two stories with 13 one- or two-bedroom units, according to a letter sent to the city by Cheyenne N. Riker, an associate with Bloomington law firm Clendening, Johnson, & Bohrer.

ICFR wants to use the buildings to help people with substance abuse and mental/behavioral disorders.

“ICFR’s long-standing operation on Bloomington’s West First Street has become a fixture, and its expansion would add additional life to an already thriving cluster of healthcare properties in the area,” Riker wrote.

ICFR operates facilities at 421 W. First St. and at 1004 W. First St.

However, for the project to move forward, ICFR needs the plan commission to recommend and the city council to approve rezoning the properties. Local planners, plan commission members, city council members and neighbors have voiced concerns about the proposal.

Properties rezoned to support development of Hopewell neighborhood

The ICFR properties used to be zoned to allow for medical-related uses, but when the IU Health Bloomington hospital moved to the east side, the city rezoned the area to R3, or residential small lot, which is “intended to protect and enhance established residential neighborhoods by increasing the viability of owner-occupied and affordable dwelling units.”

The rezoning was part of the city’s effort to establish on and near the former hospital campus a new residential neighborhood called Hopewell.

However, Riker, in the letter, said the ICFR properties were “unlawfully spot-zoned,” or singled out for different treatment to avoid the application of state or federal law. ICFR’s patients, he wrote, “are within a protected class of individuals with disabilities as defined under the Americans with Disabilities Act … and the Fair Housing Act.”

“The city specifically targeted only ICFR’s properties and spot-zoned them to effectively prohibit ICFR from expanding,” Riker wrote.

Similar arguments: Fate of Bloomington shelter for trafficked women may be heading to the courts

Riker also told plan commission members the rezoning was unfair to ICFR, because when the business bought the properties it had the “investment-backed expectation” that it would be allowed to build the medical facilities there.

Riker said the business is doing exactly what the city suggested when the city council rezoned the area in 2021. His letter to the plan commission includes a link to a YouTube video of a city council meeting on May 13, 2021.

And, indeed, after a question from council member Matt Flaherty, then-planning Director Scott Robinson said in that meeting after the areas are rezoned to R3, anyone can request a rezone — though Robinson gave no assurances such a request would be successful.

Plan commission unsympathetic to Indiana Center for Recovery claims

Riker told plan commission members Monday while the area might eventually turn into a residential neighborhood, it would, for the foreseeable future, remain dominated by medical facilities, including several near the proposed group home sites.

Plan commission members disagreed.

Commission member Hopi Stosberg, who also serves on the city council, said Riker’s statement was simply inaccurate, and the rezoning request felt “like a step back more than a step forward.”

Jacqueline Scanlan, interim director of the city's planning and transportation department, said while the area still contains medical facilities, most of them are part of ICFR.

The city changed the zoning designation because the community wants to transform that area into something different, she said. That may not be in line with ICFR, she said, but it’s in line with what the community wants.

Bloomington City Council President Isabel Piedmont-Smith agreed.

She said the proposed facilities do not fit in with plans adopted by the council, which decided to focus on housing affordability, housing supply and neighborhood stabilization, all of which are contradicted by ICFR’s rezoning request.

Piedmont-Smith does not serve on the plan commission, but called into the meeting as a concerned resident of the McDoel Gardens neighborhood.

Concerns about project, and having Indiana Center for Recovery as a neighbor

Paul Ash and Elizabeth Cox-Ash, who have lived in McDoel Gardens since 1991 — though Ash said he rode his bicycle in the area as an undergrad in the 1970s — said they oppose the project primarily because of the project’s size and because of the business’ history of problematic interactions with residents.

Ash said ICFR bought an apartment complex in the area years ago and quickly got residents, some of whom had lived there more than a decade, to move out.

The couple said when neighbors complained, ICFR, which is part of Palm Beach, Florida-based Haven Health Management, swung its corporate cudgel.

“They threatened me with a lawsuit just to shut me up,” Cox-Ash said.

That didn’t work very well, added her husband.

In the last few years, ICFR tore down some homes, Ash said, and while the business considered them “uninhabitable,” he said they were anything but.

In fact, the couple said, the neighborhood is one of the few that still offers affordable homes. Ash, a retired postal worker, described it as a “Model T neighborhood,” with smaller lots and homes.

It makes no sense, the couple said, for the city to have spent millions to acquire the former hospital property to turn it into a neighborhood, while allowing the construction of three-story buildings for medical uses.

“It’s too big, and the materials used don’t fit at all,” said Cox-Ash, a retired mortgage loan officer.

She said the neighbors suggested the business construct smaller residential facilities, but ICFR did not appear to like those ideas.

The couple and Piedmont-Smith said ICFR provides important services, but they should be offered in areas already zoned for that purpose.

Plan commission member Jillian Kinzie said the ICFR request was incompatible with what the city has outlined in its guiding documents — though she was open to looking for a route to make the ICFR project possible.

The plan commission continued the matter to its meeting on March 11.

Owners of Haven Health Management named in fraud scheme lawsuit

The ICFR was established in Indiana in 2016, according to filings with the secretary of state’s office. Kirill Vesselov was listed as president. He is listed in a subsequent filing in 2018, but the business in 2020 filed a notice of change of the registered agent. Subsequent reports do not mention Vesselov but list only Riker as the legal representative.

Riker, when reached by phone Wednesday, declined to comment. He later asked that he be emailed the questions.

When asked whether the Vesselovs are still behind ICFR, Riker said via email, "Haven Health Management is the entity that owns and operates the Indiana Center for Recovery." Haven's website lists Kirill Vesselov as the company's CEO and Riker as corporate counsel.

The ICFR got local attention in 2018 when H-T reporters revealed it was charging clients $2,300 for urine tests, although the Monroe County Probation Department was charging people only $25 for similar tests.

Vesselov and his father, Mikhail Vesselov, were among dozens of people sued by California-based pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences, which alleged the Vesselovs and others engaged in a multi-million fraud scheme.

Gilead, through its Medication Assistance Program, provides eligible uninsured people with free medication to help protect them from HIV infection. The company alleged in court documents the Vesselovs and others, through their businesses, recruited poor and homeless people, paid them small gift cards, and asked them to pretend to be patients to obtain from Gilead free medication that the Vesselovs would buy back for pennies on the dollar and sell at a higher price on the black market.

Riker said the lawsuit "has no connection to the Indiana Center for Recovery or its zoning application. It was dismissed in April 2022."

Court records show the case against the Vesselovs and some of the other defendants was dismissed at Gilead's request after the parties reached a settlement.

Haven, the Vesselovs' Florida company, also recently bought the former Ascension St. Vincent Dunn Hospital in Bedford, and plan to open it this spring as part of the ICFR.

Boris Ladwig can be reached at bladwig@heraldt.com.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Indiana Center for Recovery seeks to build group homes in Bloomington