In Indiana, what kids learn about the Holocaust depends on where they go to school

The Nazi concentration camp officer screamed in the unheated barracks, telling the group to get ready for the showers.

The women and girls had been holed up for days in a windowless, locked cattle car on the trip from Poland. They were filthy and hungry; some of their fellow Jews died during the long ride. There was no food, no water, no daylight except what seeped in the cracks of the cattle car.

Aware of what showers could mean, the group was uncertain of their immediate fate. Would their cold, naked bodies be gassed in the showers and then burned in huge crematorium ovens that emitted black smoke?

The water blasted on with a frigid force. There was no death for this group. Most would later die, and their bodies burned. The horrors of concentration camp life are described in the young adult novel, “The Devil’s Arithmetic,” a volume often used in Holocaust education that doesn’t hold back the atrocities of our history.

The Never Again Education Act was passed by Congress in 2020, requiring all states to provide Holocaust education in public schools.

Only one of 13 states to do so, Indiana has had an unfunded recommendation since 2007. Even today, implementation differs from school to school, from a brief nod in a 20th Century history unit to a semester-long interactive unit with field trips and speakers, depending on funding and will.

Partnerships among local colleges, museums, civic organizations, libraries, churches, and a group of women called the Committee to Promote Respect in Schools (CYPRESS) have advocated for and sponsored Holocaust education since the 1990s. Despite what facts prove — that 6 million European Jews lost their lives in Hitler’s “Final Solution” — there is more public antisemitism and Holocaust denial than in recent years.

In September, the Rechnic Holocaust Series at the University of Southern Indiana brought in award-winning author Margaret McMullan to speak about her book, “Where the Angels Lived,” her family’s difficult and poignant trip through Poland to uncover a hidden history. During McMullan’s visit, CYPRESS arranged for her to talk to more than 2,000 students throughout the Tri-State. She shared her experience researching her Jewish roots, the rise of authoritarianism today, and ways to prevent it.

McMullan noted that a young man approached her after her Castle High School talk. He said, “Thank you for coming. This is the first I’ve heard about the Holocaust.”

This anecdote underscores why the work of Holocaust educators is more important than ever today.

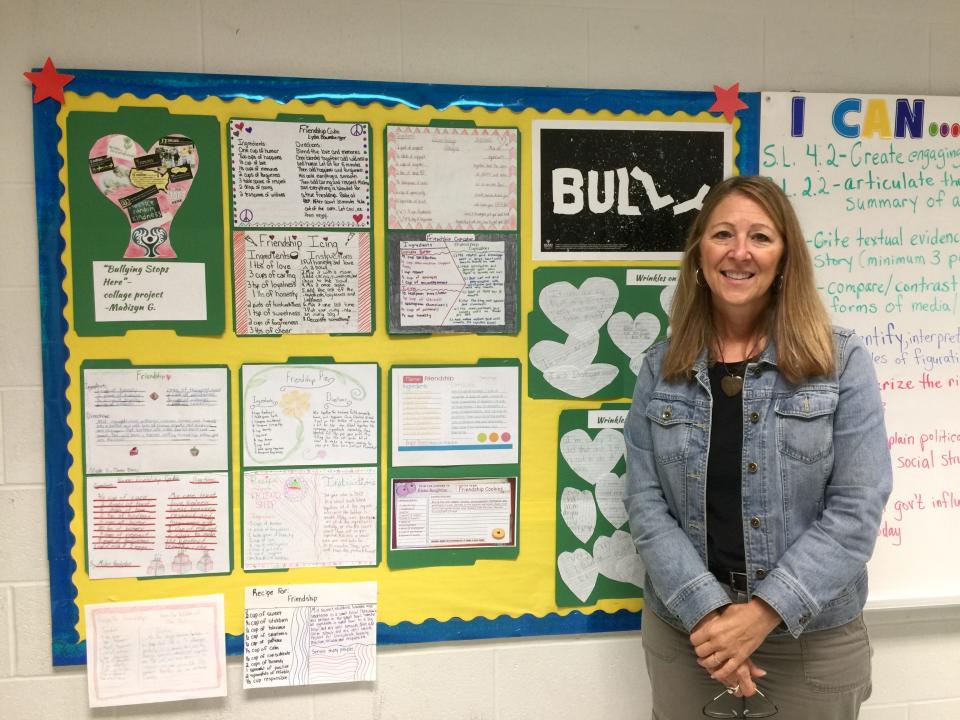

At Castle South Middle School, Sarah Rollins taught a non-credit Holocaust education class.

“Students were assigned a survivor and a victim to research and become the expert about,” Rollins said. “The final project was a museum night. Students created displays, spoke about their exhibits, and discussed their survivors and victims with attendees.

“During the course, students Zoomed with a survivor born in a cave because his parents were part of the Resistance.”

Rollins is one of the newest members of CYPRESS. She initially learned of the group when she took an Echoes and Reflection course on the Holocaust offered by the local group.

“In 2019, I was picked to go to Poland to participate in an extensive Holocaust study, which was life-changing. I was reintroduced to CYPRESS due to my Holocaust museum night and was asked to join,” she said.

Rollins has been moved to Castle High School, hoping to foster more Holocaust education.

Several other public and private school teachers serve on the CYPRESS committee and have moved Holocaust education forward.

Rebekah Hodge is retired from Thompkins Middle School, where she taught Holocaust education for many years.

Hodge used the book "The Devil’s Arithmetic," noted earlier.

“My students could relate to people having hard times. Kids need to be exposed to it," she said. "Some parents were worried, but you cannot soften something as horrible as the Holocaust. If you change the image, that’s not what happened.”

“Students are very interested in personal stories. I learned of the Shoah Testimonies at Central Library and took my students there. After listening to several survivor stories, I put the students in pairs and had them do a talk show. The students had to rely on each other; one was the host, and the other was the victim.

“I was so moved, I had to put my head down on the desk,” Hodge recalled.

Lisa Muller is a retired high school teacher who taught students about the Holocaust but also worked on the national and international level with Holocaust educators. When Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation needed a school curriculum, Muller traveled to California for several weeks to work with a select small group of teachers.

She is a former fellow of the National Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., worked on their school curriculum, and is active with the National Catholic Center for Holocaust Education.

Her involvement has been a beacon to local teachers, as she has traveled to Europe four times to visit Holocaust sites and also met many others doing similar work, including a man who worked for Otto Frank after the war. Most amazingly, she ate dinner with Miep Gies, who most know as one of the people who hid the Frank family in Amsterdam.

Muller loves to help teachers understand the significance of the Holocaust.

“When you see the light go on in a teacher’s eye, you know they are returning the message to their students," she said.

Even retired, Muller is feisty about why this is important. “People in Europe didn’t believe it could happen to them. People just lived their lives.

“We have a choice about how we want to live and how we want to treat people. Right now, we have a choice,” Muller added, “We may not always have a choice.

“The Holocaust was a real thing that happened to real people. It was not inevitable. People choose to do or not do. We create our problems and can solve our problems.”

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: What do Indiana schoolchildren learn about the Holocaust?