Indiana settles death of inmate who burned alive in his cell in 2017 for nearly $4 million

Indiana and its Department of Correction have resolved a federal lawsuit involving an Indiana State Prison inmate who burned to death in his cell in April 2017.

But the sister of inmate Joshua Devine says she would have preferred an arrangement in which someone would be held accountable for her brother’s “heartbreaking” death.

“The settlement itself was not what I wanted,” Krystal Devine wrote in a statement about the nearly $4 million agreement. “I eventually felt like that was the only option, (to) settle because no one would truly be held accountable. No one would have to be locked in a cell like my brother.”

Depositions and a judge’s ruling over Joshua Devine’s death painted a picture of an understaffed, undertrained custody staff and a prison in which electrical problems, faulty equipment, a lack of cell-house sprinklers and too few fire extinguishers led to his burning in his cell for about 30 minutes while other prisoners yelled in vain for correctional officers to release him.

‘Dangerous lapses’: 5 years later, effects from a deadly Indiana State Prison fire linger

The pact, reached several months ago but whose terms were only recently released to The Tribune, included $3,925,000 to be paid to Devine’s family. The pact also notes the DOC and several employees named in the lawsuit deny the allegations surrounding the 30-year-old’s death on April 7, 2017.

A DOC spokesman asked Wednesday about any changes since Devine’s death or any details into investigations surrounding the January 2023 death of 48-year-old Michael W. Smith — who also burned to death in his cell — has not yet responded.

A Mishawaka woman who was on the phone with several prisoners the night of Devine’s death recalled in an earlier Tribune article of hearing Devine’s anguished screams and the chorus of other locked-up prisoners yelling hysterically for the attention of prison authorities.

Devine’s mother, Barbara Devine of Indianapolis, filed the federal lawsuit in late 2018 alleging wrongful death, negligence and several violations of Devine’s constitutional rights, including failure to protect and deliberate indifference to unsafe conditions. After Barbara Devine’s death, her mother, Denise Dwyer, represented the estate.

'Please help this man; he's going to die'

Three correctional officers were on duty in B Cell House that night. After about 9 p.m., when prisoners are counted and locked in their cells, Sarah Abbassi, Justin Rodriguez and Promise Blakely left the five-floor cell house to do paperwork in nearby areas of the prison.

The three officers “were all relatively new to the job,” Chief Judge Jon DeGuilio wrote in his 2022 order allowing the lawsuit to continue, pointing out that once prisoners are locked in their cells for the night, “the only way for them to get the guards’ attention about an issue was to yell and make noise.”

Shortly after 9 p.m., Devine plugged in the television in his cell, and it caught fire. Warden Ron Neal issued two press releases within weeks of the incident suggesting Devine was tampering with the outlet, starting the fire. Though the fire was ruled to be accidental, the judge noted that the fire marshal determined Devine merely plugged the TV in and then tried to pull the cord back out when the fire spread to him, then to his bed and the wall, quickly engulfing the cell in flames.

Tina Church, a Mishawaka legal investigator who works with many ISP prisoners, said in 2022 that she happened to be speaking with a client who was still out of his cell using a phone on Devine’s floor when the fire broke out.

“I could hear him,” Church said of Devine’s panicked voice, even over the yelling of the other prisoners who were at first trying to help and then panicking themselves as heavy black smoke filled the range and the flames grew. “The men were freaking out. They were screaming, they were crying, they were hysterical. … All these people screaming, ‘Please help this man; he’s going to die!’”

Several other prisoners called her over the next 30 minutes as no prison staff responded and Devine remained in his burning cell, Church said, so that she could be a witness to let his family know what happened.

“Blakely, Abbassi and Rodriguez heard and understood the yelling immediately after it began,” the judge wrote, citing several depositions and reports throughout his ruling. “Despite being able to hear prisoners screaming about a fire, it took at least 15 minutes before any of the three took action.”

Even then, when Rodriguez went up to the fifth floor, he did not take a fire extinguisher, did not release Devine from his cell and did not even take keys with him.

“When he got to Devine’s cell, Devine asked Rodriguez to let him out,” the judge wrote. “Other prisoners asked Rodriguez to let Devine out of his cell. However, Rodriguez, without uttering a word to the prisoners, turned around and walked away.”

Capt. Jeremy Dykstra, who no longer works at ISP but was watching the fire from an office security camera that night, said in a deposition that the fire “was shooting out the cell, probably like 5, 6 feet.” He compared the scene to the movies, with the fire “coming back out, like a fire-breathing dragon.”

Blakely and Abbassi also took no meaningful action, according to depositions. Abbassi issued a “fire code” at 9:45, 30 minutes after prisoners first started yelling for help. Two officers with keys finally reached the fifth floor.

“By this point, Devine was pressed against the front of the cell, not saying anything,” the judge wrote. “According to Rodriguez, he was just screaming.”

By the time Devine’s cell was opened, Church said, he was found essentially melted onto the metal bars of the cell door, apparently having tried in desperation to squeeze his body through. Afterward, prisoners used shovels to remove melted fat from the floor, she said.

‘Dangerous lapses’

Among the issues that night:

• There are no sprinklers in the cell houses of ISP, which was built in 1860 and is the oldest prison in Indiana.

• Fires are fairly routine at ISP. Sometimes, prisoners will set fires for attention or to protest perceived injustices. But the judge wrote of “dangerous lapses” the supervisory defendants, including Neal, should have protected inmates from.

“Each one of them was aware of an abundant number of safety hazards at ISP,” DeGuilio wrote. “One particularly glaring safety hazard was the widespread, persistent issues with fires and electrical outlets sparking. …

“Prisoners considered plugging devices into outlets to be risky, due to them frequently catching fire,” DeGuilio wrote. “And just a few months prior to the fire on April 7, 2017, a large electrical fire on the 400 range (fourth floor) of the B Cell House was reported.”

Prisoners must buy their appliances through the Department of Correction, Church pointed out, adding that Devine’s model has since been recalled because of safety issues.

No employees named in the lawsuit were disciplined as a result of what happened the night of the fire, according to a spokesman for the Indiana State Personnel Department.

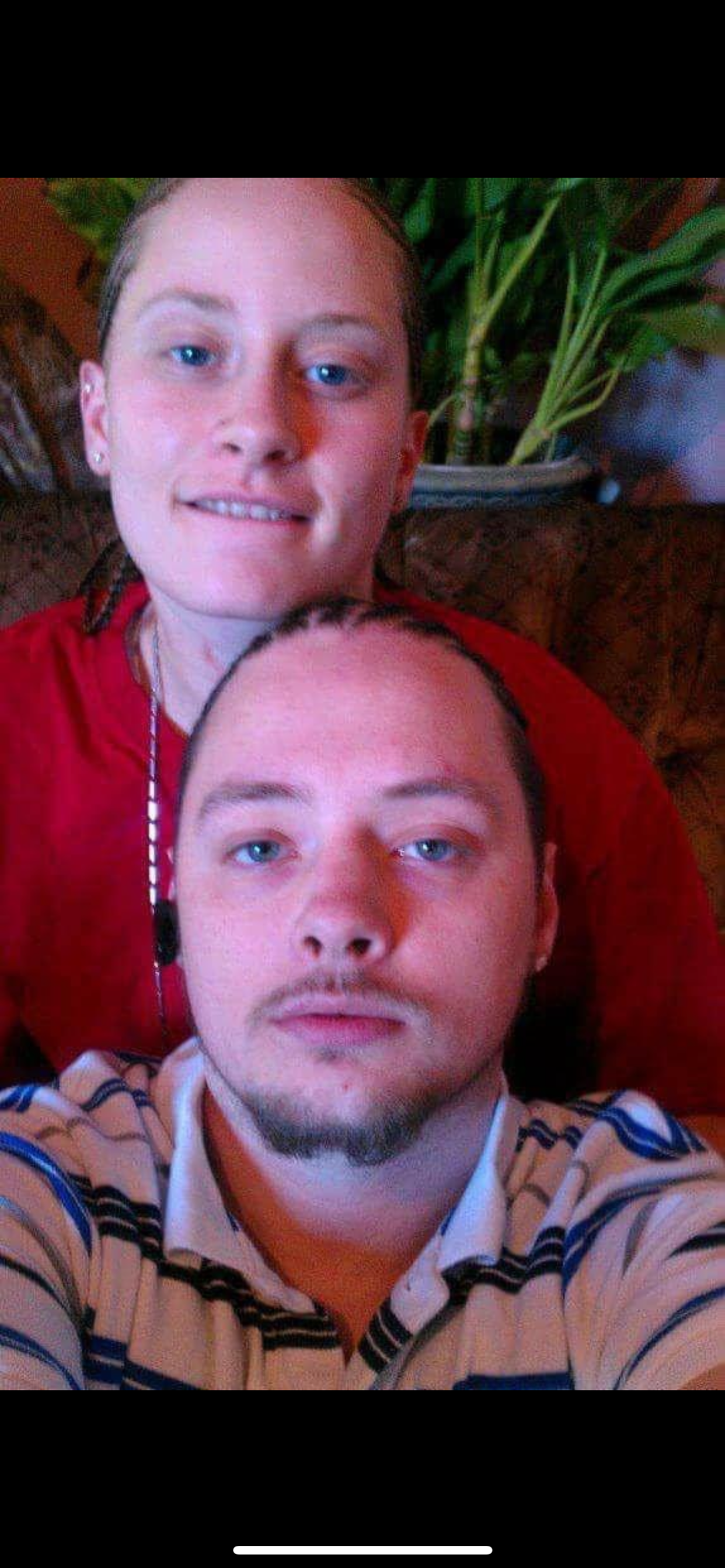

Joshua Devine, whose nickname was Spider, was born to a poor family in Indianapolis, Church said. He was raised without a father and apparently had drug issues. The court dockets of two earlier, lower-level cases in Marion County refer to psychiatric examinations.

Devine was serving 16 years on a robbery charge out of Marion County, beginning in 2013. One of the officers described Devine as quiet and not a troublemaker.

“I do hope legislators pay attention to what happened to my brother,” Krystal Devine said. “What they allow to happen to the inmates doesn’t only affect the inmates, it affects their loved ones as well. It’s quite alarming knowing there are people running a facility (who are in charge of other humans) that are capable of watching someone burn alive.”

Krystal Devine said her life is shattered by the loss of the brother she called “TwinFace,” because they looked so much alike.

“The inmates are humans too!" she said. "Just like the guards want to go home at the end of their shift, they too want to go home at the end of their sentences.”

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: State pays $4M to family of Indiana State Prison inmate burned alive