An Indiana species might be added to the endangered list, and it looks like bird poop

Solitary polar bears perching on isolated ice caps. Giant pandas chewing fresh bamboo. Bald eagles soaring low over wild rivers. These iconic images often come to mind when headlines pop up about endangered species.

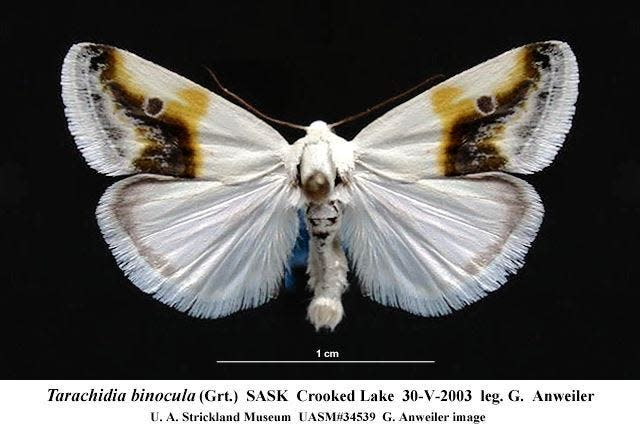

But Indiana may have a new poster-worthy species this year: A moth that looks like bird poop.

The prairie tarachidia, also known as the Prairie Bird-Dropping moth, is one of several species the Indiana Department of Natural Resources is proposing for addition to the state's endangered species list. The moth is valued as an "indicator," the term for a species which helps signify the health of a particular habitat, and it’s also a vital link in the food chain.

Indiana: 5 species the Indiana Department of Natural Resources has worked to restore

The bird-dropping moth and other species proposed for addition — including the fat pocketbook mussel, the pallid shiner and the crawfish frog — may not be as iconic or photogenic as some species, but each is an important part of Indiana’s various ecosystems.

How many species are endangered in Indiana?

The DNR has about 150 species from across the state listed as either endangered or of special concern. The state's endangered designation means a species is in immediate jeopardy with limited chances of survival or recruitment. Species identified as a special concern require monitoring due to declining populations or habitat loss.

The state in 1973 passed the Nongame and Endangered Species Conservation Act providing DNR the ability to investigate Indiana’s native species and make determinations to manage and conserve endangered species.

The act gives DNR’s director the autonomy to act independent of federal endangered species provisions and look within the state to provide native species separate protections. The state does, however, also include on its list all federally listed species.

Drop in annual giving makes protecting species more difficult

This year marks the department’s 40th anniversary for the Nongame Wildlife Fund, which pays for habitat management and conservation practices through donations from Hoosiers. Money comes to the fund through donations from individuals receiving state income tax refunds and direct giving. The fund has so far generated about $13 million for conservation work, including efforts to protect endangered species.

More: Reporting sick or injured wildlife in Indiana: 5 things to know

Scrub Hub: Where are the best places to spot bald eagles in Indiana?

Annual giving has fallen off in recent years, making it difficult to do all the work needed to protect species. Proposed federal legislation could reverse that trend, adding $18 million a year in Indiana if it is approved.

The state works on a two-year schedule when considering listing or delisting endangered species, said Scott Johnson, wildlife science supervisor with the DNR. It's done through administrative rule and is a lengthy process involving public comment periods.

Species of special concern can be considered every year, and making additions to that list does not require the same lengthy process.

“It kind of serves as an early warning list a little bit, but not always” Scott said of the special concern list. “If we find a new species in the state, it may be listed there until we get enough information to see its true distribution.”

When are species removed from the endangered list?

Delisting, or moving a species off the endangered or special concern lists, isn’t always straight forward. Scott said the osprey is a good example of a species being removed from the endangered list after an initiative that had very clear recovery goals and succeeded.

The bird was reintroduced to Indiana in the 1990s, and rather quickly reached a benchmark of 50 nests in the state — enough for the DNR to recently remove it from the endangered list.

“The osprey was not the norm because it’s really difficult to get accurate population sizes with some certainty,” Scott said. “We look for trends that populations are generally increasing as well as the distribution: Are they spreading throughout the state?”

These are not hard and fast numbers, he said, but combining these metrics gives state wildlife experts the knowledge they need to determine if and when species have reached sustainable populations.

Multiple bat species on endangered list

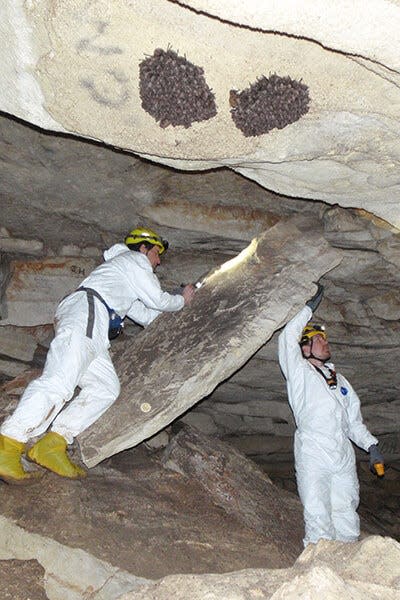

Another important initiative the DNR is currently working on is to restabilize populations of the Indiana bat. The Indiana bat and other bats are important in many ways, Scott said, including their appetite for the spotted cucumber beetle, an agriculture pest.

The state added three new bat species to the endangered list in 2018 following large declines in population due to white-nose syndrome, which is caused by a fungus that gets on the bats’ skin.

Since bats in Indiana hibernate in caves, they were particularly vulnerable to white-nose syndrome as they’re closely grouped together.

While osprey, bats and other recognizable wildlife are easy for Hoosiers to identify, more obscure plants and insects also need attention.

More: 'An opportunity to be surprised': Why and where to start birding in Indiana this summer

More: Indiana sanctuary takes in rescue cats from 'Tiger King Park' of Netflix fame

Working to bring species back

For a species to reestablish a healthy population, it needs habitat.

Evan Hill, stewardship director of the ACRES Land Trust, said most of Indiana’s listed species are found in wetlands, which are increasingly rare and easily degraded.

Gov. Eric Holcomb and the state legislature last year repealed Indiana’s wetland law, striping protections from some of these habitats as proponents argued it stood in the way of builders and developers.

Funded with mostly private grants, ACRES acquires land to put into preservation.

“We look for those areas that have the greatest risk and yet the most potential to hold those species,” Hill said.

The organization has five or six priority areas in different locations, usually around existing preserves. Hill and others at ACRES look at all kinds of land for preservation from farmland to pristine natural areas.

Invasive plants are a main cause affecting some of these lands ACRES acquires, Hill said, and restoration begins with a plan to eradicate them using herbicides or mechanical harvesting.

“Generally, once we get rid of the invasive, the native seed bank is still there and those native plants come back in,” Hill said. “But it varies so much, site to site, and often on funding as well. It’s usually a three- or four-year endeavor, then at the end we’re usually looking at native plants coming back up.”

Invasive plants often don’t offer nutritional value to native wildlife, so getting native plants back to a thriving population will have a direct positive effect to any endangered species.

More: After a blow from a new law, this is how activists are working to protect wetlands

More: Indiana one of most polluted states. New report says legislature gets a D+ on green bills.

While ACRES focuses on land, DNR also puts an effort into managing aquatic species.

The department delisted six species of freshwater mussels in 2018, but not because of a population rebound. It was the opposite: They were no longer found in Indiana waterways. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also delisted 23 freshwater mussels last year due to extinction.

Mussels are great at filtering out suspended materials and bacteria from waterways and are typically indicators of good water quality and a healthy habitat.

“These guys need flowing water and our major waterways, the Wabash River, White River and Ohio River support some of these listed species,” Johnson said. “We do a lot of work in that area like outreach efforts to take care of water quality improvements and practices that reduce sedimentation.”

A recent paper from the Environmental Integrity Project shows Indiana has more miles of polluted waterways than any other state, the Star reported earlier this month.

As DNR continues its restoration and management efforts, it relies on funding that has that has been in slight decline.

Funding wildlife management

Indiana’s nongame wildlife fund was first set up through the state income tax form. Hoosiers who qualified for a refund were able to donate all or part of that into the nongame fund.

“That’s used to support the development of projects and programs to protect species,” Johnson said.

Residents have donated nearly $13 million to the fund since its inception but, according to a recent DNR report, yearly figures are falling. In 2019, donations to the fund totaled about $188,000, which was 17% less than the previous year, the latest report says.

During its peak in 2009, the fund received about $550,000.

The state also began receiving funding to help declining species through a federal grant program established in 2001. The State and Tribal Wildlife Grant Program provides yearly allotments to states. Indiana has received about $18.6 million to support species conservation since the program began.

A new proposed federal bill, however, could drastically increase federal funding for endangered species. Indiana stands to receive $18 million each year if the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act passes.

Emily Wood, executive director of the Indiana Wildlife Federation, said the bill is a means to proactively address wildlife in need of recovery. The biggest issue with endangered species, Wood said, is that Indiana is not nimble enough and does not have enough funding for staff and resources to roll out these restoration projects. It’s an issue most states face, she said.

“It takes about 12-15 years for species to start receiving actual on-the-ground restoration type projects once listed,” Wood said. “So we are listing species on the brink but we are not rising to the matching scale of the problem with what we have to address it. This bill aims to address that issue.”

“(Federal funding) is now less than $1 million. It’s hard to explain the magnitude of work that would be able to be done if this bill passes," Wood said. "It’s revolutionary legislation."

Legislation like the federal wildlife act also helps protect species that are not as popular or iconic. Government agencies and non-profits have to spend time convincing people for funding initiatives around species that are not as iconic as Bald Eagles. Groups can be more proactive at saving these species if the funding is already there through this legislation

“I really hope the people of Indiana understand how important it is right now to reach out to senators and house representatives to say, ‘Hoosiers want and need the Recovering Wildlife Act,’” she said. “We need that funding to address species across the state.”

Karl Schneider is an IndyStar environment reporter. You can reach him at karl.schneider@indystar.com. Follow him on Twitter @karlstartswithk

IndyStar's environmental reporting project is made possible through the generous support of the nonprofit Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Prairie Bird-Dropping moth could be added to Indiana's endangered list