How an Indiana University athlete broke the segregation barrier at The Gables in 1947

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: In honor of Black History Month, The Herald-Times is publishing Black stories, both current and historical, throughout the month of February. Look for them on weekdays. Send your feedback and suggestions about this series to rksmith@heraldt.com.

Two years after their unprecedented victory, a wall-sized portrait of the 1945 championship Indiana University football team hung proudly within the Gables Restaurant at 114 S. Indiana Ave. That season was a point of Hoosier pride, and it only made sense for the Gables, a then-extremely popular eatery for IU students, to celebrate these players in an elaborate way. With the canvas looming over their tables, the football players could tip their heads back and take it all in, pride undoubtedly swelling in their chest as they examined the grainy texture of their visages.

One of the star players, George Taliaferro, wasn't able to get that close of a look.

Back in the 1940s, an invisible but ever present line was drawn between the Gables' entrance and Indiana Avenue for Black residents like Taliaferro. Instead, Taliaferro had to press his head tightly against the glass window to steal a peak at his likeness.

Despite the intervening decades since he last took the field as a venerated football player, Taliaferro's is a lasting legacy at IU. In 1945, Taliaferro — at the time, only a freshman rookie hailing from Gary — had a big hand in the Hoosier football team's trailblazing journey to a Big Ten championship, which still serves as the program’s only undefeated season to this day. Taliaferro would later make history as the first African American player selected in the NFL Draft. But even before then, he had already made a mark in Bloomington for both his on- and off-field victories.

From our archive:IU Football's George Taliaferro remembered for legendary career, smashing racial barriers

While Taliaferro was a student in the 1940s, Bloomington was still rife with segregated spaces. With about two decades still to go before The Civil Rights Act of 1964 would supersede all state and local laws requiring segregation, Taliaferro was heavily restricted in where he could eat, shop and even live (with IU's dormitory system closed to Black students, he had to live several miles off campus). Even restaurants such as the Gables, which proudly brandished Taliaferro's success as an athlete in its interior, would not serve African Americans.

While his teammates could catch a quick lunch at the Gables, Taliaferro had to walk several miles each day to take his meals at home before returning to the university. When Taliaferro began pushing to desegregate both IU’s campus and the Bloomington community, that restaurant — a prime example of how he and his peers were treated differently — seemed like the perfect stage to make a stand.

At Taliaferro's urging, former IU president Herman B Wells called the Gables to ask if he and the student could dine there. While the owner initially refused, he and Wells eventually came to an agreement: Taliaferro and another African American friend could dine at the restaurant for one week. If there were no complaints from white patrons, two friends could join their party for the second week. If there were still no complaints after the two-week period passed, the Gables would open to all African Americans.

Taliaferro and his friend dined there daily for a week. There were no complaints.

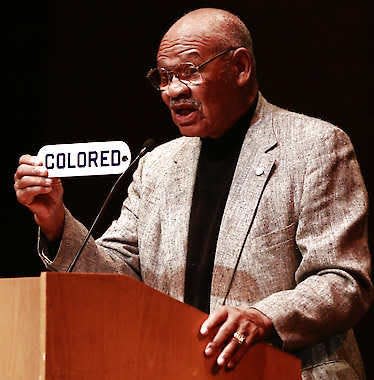

When the restaurant was integrated without incident, other Bloomington businesses followed. Taliaferro remained at the forefront of pushing these boundaries, sitting in sections reserved only for white patrons at the Indiana and Princess theaters. During one such trip, he took a screwdriver and uninstalled a sign that read "Colored," which he held onto for the rest of his life.

Taliaferro was drafted by the Chicago Bears in 1949 and later played for professional franchises in Los Angeles, New York, Dallas, Baltimore and Philadelphia. He died in 2018 at the age of 91. While he may be remembered across the country for his impressive tenure on the national scale, Bloomington residents will remember his tireless fight against local injustice.

“He will go down in history because he made his name as a sports figure,” IU historian Jim Capshew told the H-T in a past report. “He went on and became an inspiration for the whole community.”

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Ending segregation in Bloomington, George Taliaferro, Herman B Wells